His name was Daniel Sheets Dye. And he was obsessed.

In 1909, the 25-year-old college grad signed on with a Baptist missionary society to help establish a medical college in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, western China. Sichuan in those days was literally beyond the edge of our world; civilized, but alien. Western influence hadn’t made the slightest dent.

I can’t tell you what made Daniel Dye, a square-jawed Ohio farm boy, make a long-term commitment to teach science in Chengdu, a 2000-year-old city he’d probably never heard of.

But as he packed his bags, Dye’s old professors urged him to get a hobby — something to stave off homesickness and culture shock ten thousand miles from home in a land that probably never heard of Cleveland or Columbus, either.

And after Dye settled in, he got his hobby.

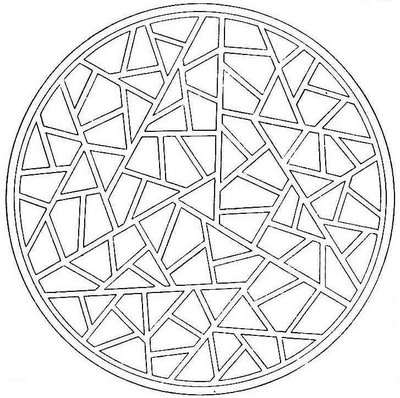

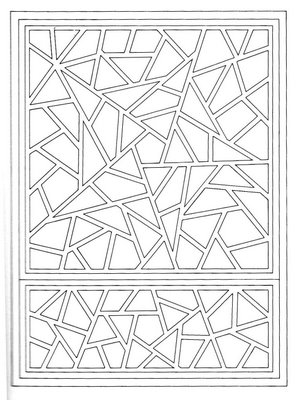

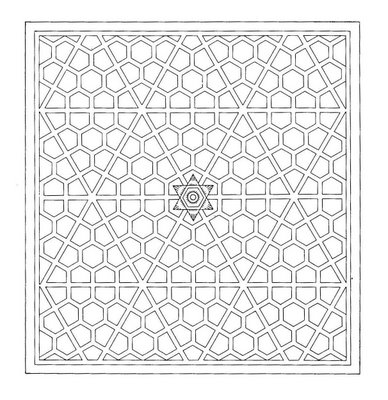

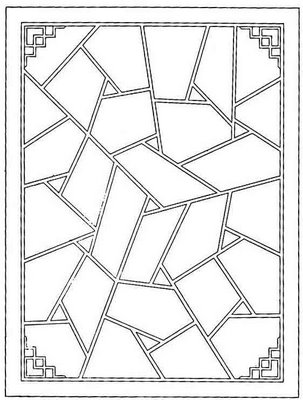

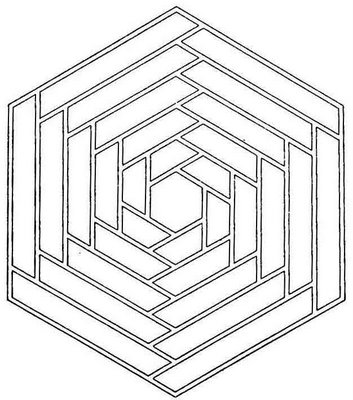

One day he was touring a shrine to a famous poet when he saw some Chinese lattice windows of unusual design. In traditional Chinese architecture, windows are made of a decorative wooden lattice with a sheet of rice paper glued to the inside to block the draft. Lattice windows let in the light, if not the sights; glass windows hadn’t made it to Sichuan yet.

Dye had noticed simple lattice windows before — grids and so forth — but these were special. He immediately copied down 20 designs and took them back to the university. Something about the intricate lattices — perhaps the underlying maths and geometries that informed their design — zapped Dye’s systematic Baptist brain. He took his copies home and set out to research the history of Chinese lattice windows.

But there wasn’t any. Lattice windows weren’t considered art; they were simply something that carpenters created using folk designs that were passed down through the generations. Dye found just one book on the subject, 300 years old and “with a limited commentary.”

But now he noticed lattice windows everywhere he went; he saw similar designs and motifs from place to place, and others that were wildly different than anything else.

But even as he began to study the lattice, it began to go away.

The Manchu Dynasty was collapsing, China sank into turmoil. Everywhere, old buildings burned down or blew up in insurrections, riots, clashes between rival warlords. Lattice windows began to disappear; in the new buildings, glass windows replaced them.

So Dye decided that he would be the scholar of Chinese lattice wherever he found it — in windows, on the side of buildings, carved into wooden boxes. Before it vanished forever.

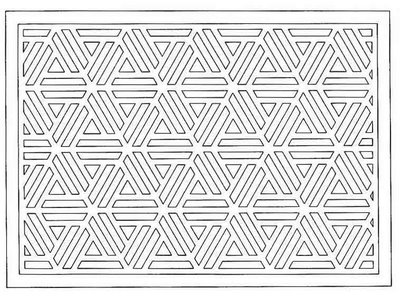

He made hundreds, maybe thousands of drawings and rubbings and measurements in the street and on the road, where he traveled by sedan chair in convoys with other notables. Dye said that you could always tell which sedan chair he was in because it was likely to pull over unexpectedly so he could jump out to sketch an interesting window. And of course curious locals would invariably crowd around the odd-looking foreigner. It wasn’t always easy to get those drawings made.

Dye even taught one of his Chinese assisting teachers to use a mechanical drawing set and transcribe Dye’s rough sketches into permanent, precise drawings in his spare time. (It’s unclear precisely how “spare” that time was to the Chinese gentleman, though Dye kept him at it for 20 years.)

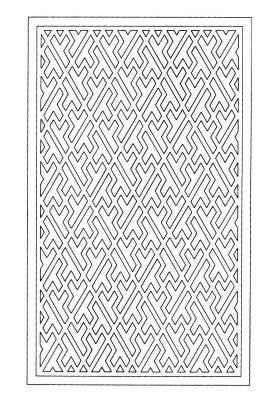

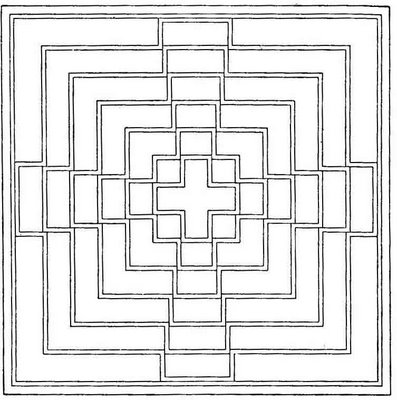

Where certain lattice designs had Chinese names, Dye identified and recorded them; where there were no names, he made his own. He devised a complete classification system for Chinese lattice design based on the basic motifs he identified, and placed each and every one of his designs in it, along with the precise location of the original and what he could find out of its age and background.

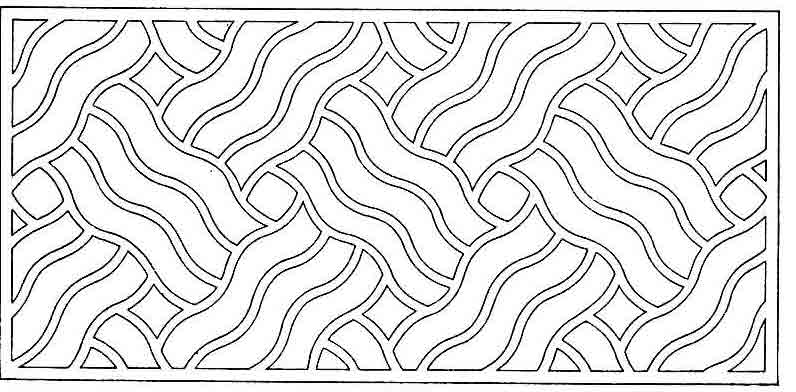

Dye figured out the principles behind each type of lattice design in his classification scheme and developed procedures for replicating every single one of them. And he never stopped trying to figure out What it All Meant. Some of the designs had themes he could figure out from Chinese cultural references, but the rest — Where did they come from? How old were they? Who invented them?

All the swastikas that recurred over and over — religious, or just a folk motif? And then he started looking at patterns woven into the belts of Tibetan herdsmen and saw many of the same patterns he saw in his windows. And he went to Japan, and Korea and even back to the states and saw lattice everywhere and noticed similarities everywhere. What came from what? Who influenced who?

Daniel Sheets Dye never did figure “it” all out. Maybe there was nothing there, or maybe too much. His lattice designs could have come from a hundred places, and moved on to a hundred places and mutated along the way; folk art is like that, especially in a cultural crossroads like western China.

But after he’d spent 25 years in China — where did the time go — Dye took his mass of material and published an awkwardly-written book with an extensive collection of drawings arranged according to his new classification system. And thus appeared the first treatise on Chinese lattice design in 300 years. There have been no others, since. There may never be. Who else would care that much? And even if they did, how many lattice windows are left?

Dye stayed in China until the Communists rolled into Chengdu in ’49, and then went home to the States — though I suspect it wasn’t “home” anymore. The medical school he taught at is still operating, by the way.

Daniel Sheets Dye lived on for many years and never gave up on lattices — and never achieved the “Big Picture” synthesis he’d been hoping for, either. Before he died, though, he apparently sold the rights to his works to Dover Publications, that eccentric reissuer of obscure and forgotten reference books and literature. And Dover has kept it in print ever since.

After Dye died, Dover even published additional lattice patterns from Dye’s papers as an artists’ design book.

Which is why both books were here for me to find — at a ridiculously low price — on the “New Arrivals” cart at Logos used bookstore in Santa Cruz some time back. I marveled at the odd patterns and strange geometries, unlike any I’d seen. I found them curiously satisfying on some visceral, non-intellectual level. Perhaps I felt what Dye had felt as he hopped from his sedan chair on a bustling street in Sichuan, pencil and paper and measuring tape in hand, at the sight of a mesmerizing lattice window. I bought them both; I see at least a couple of good stained glass projects in Dye’s collection.

Yes, Dye was obsessed. But obsession, though not always the most pleasant of personality traits, often leaves something behind for the rest of us to enjoy. And if you troll the Internet you will find artists and craftspeople and even mathematicians and programmers whose work, they will gladly confess, was influenced by a Baptist science teacher’s book on Chinese lattice designs. Designs which might never have made it out of China — or survived at all — if Dye had decided to take up cooking instead.

All hail to the obsessed! And thank you, Mr. Dye.