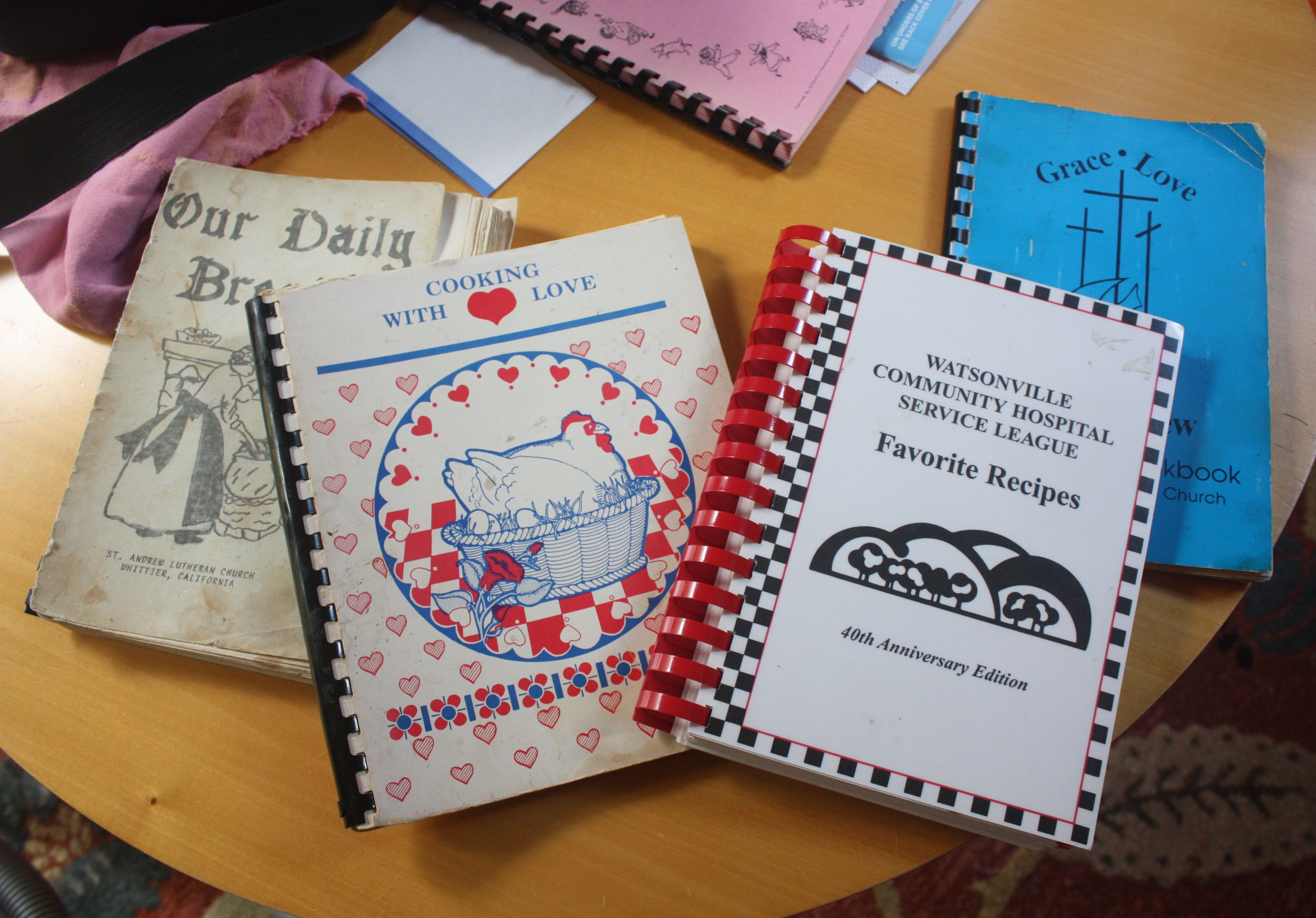

I picked up some old church cookbooks at a rummage sale last Saturday. Four of them peeked out of a box as I wandered by. They beckoned to me.

“How much?” I asked a grizzled churchwoman.

She sniffed. “A buck for all of ’em.” Deal. I took them home and leafed through them. I love amateur cookbooks.

Church and community cookbooks, like Rodney Dangerfield, don’t get no respect. And they deserve some. They were and are a venerable fundraising scheme for churches, charities, clubs, or other non-profits that want to raise a few bucks. Community cookbooks go back decades, to the advent of inexpensive printing technology. I’ve seen one from the 1880s.

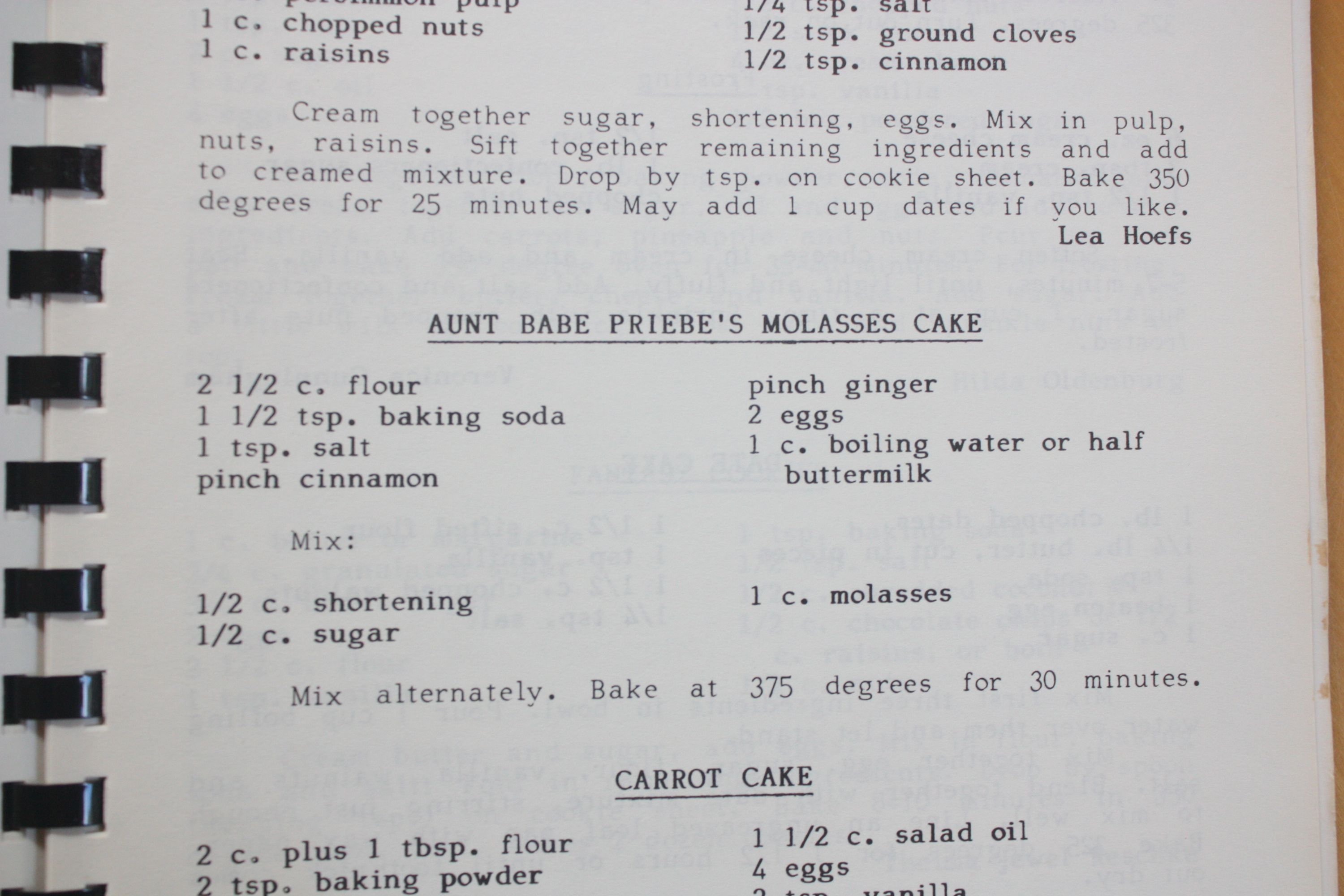

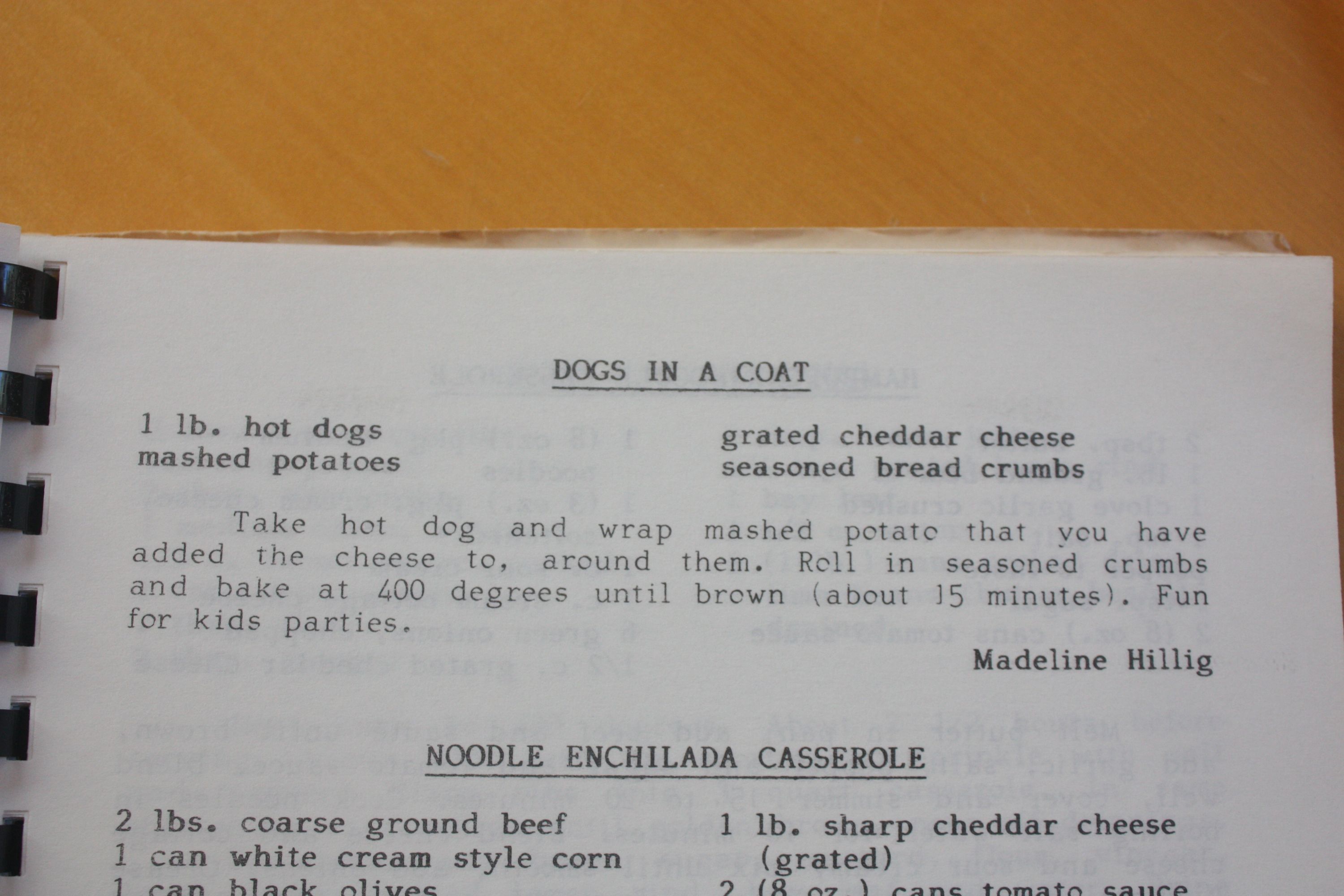

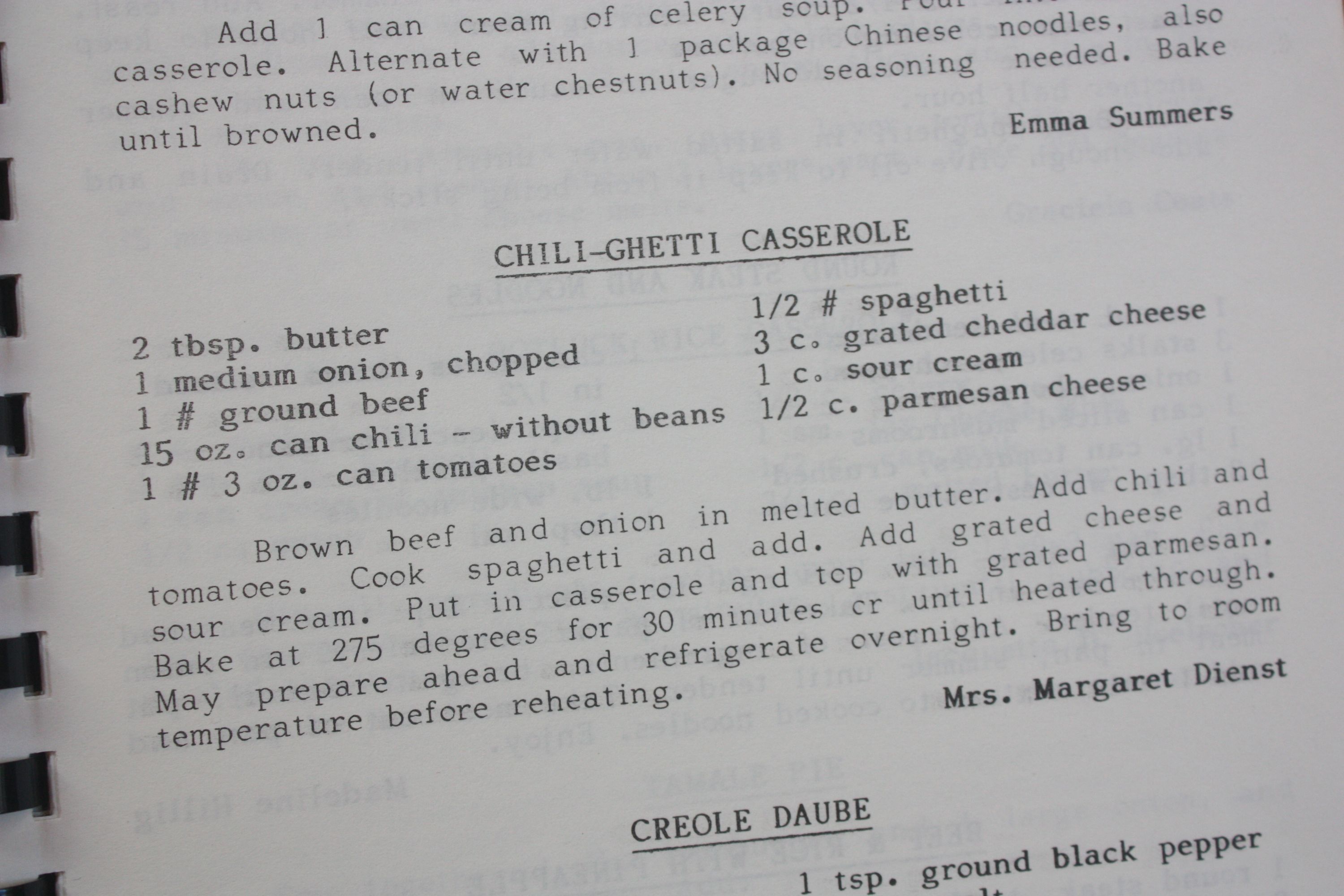

The ladies of the congregation would all kick in a recipe or four. A volunteer typed them all up in manuscript form and mailed them to a distant cookbook printer in a low-wage area. The printer photographed the pages “as is” and made printing plates from them. You could pay for real typesetting if you wanted to be fancy. Most didn’t.

In a few weeks, the printer would return to sender a crate of cookbooks with clunky plastic spiral binding and whatever cover art was provided. Then the congregation would try to sell them.

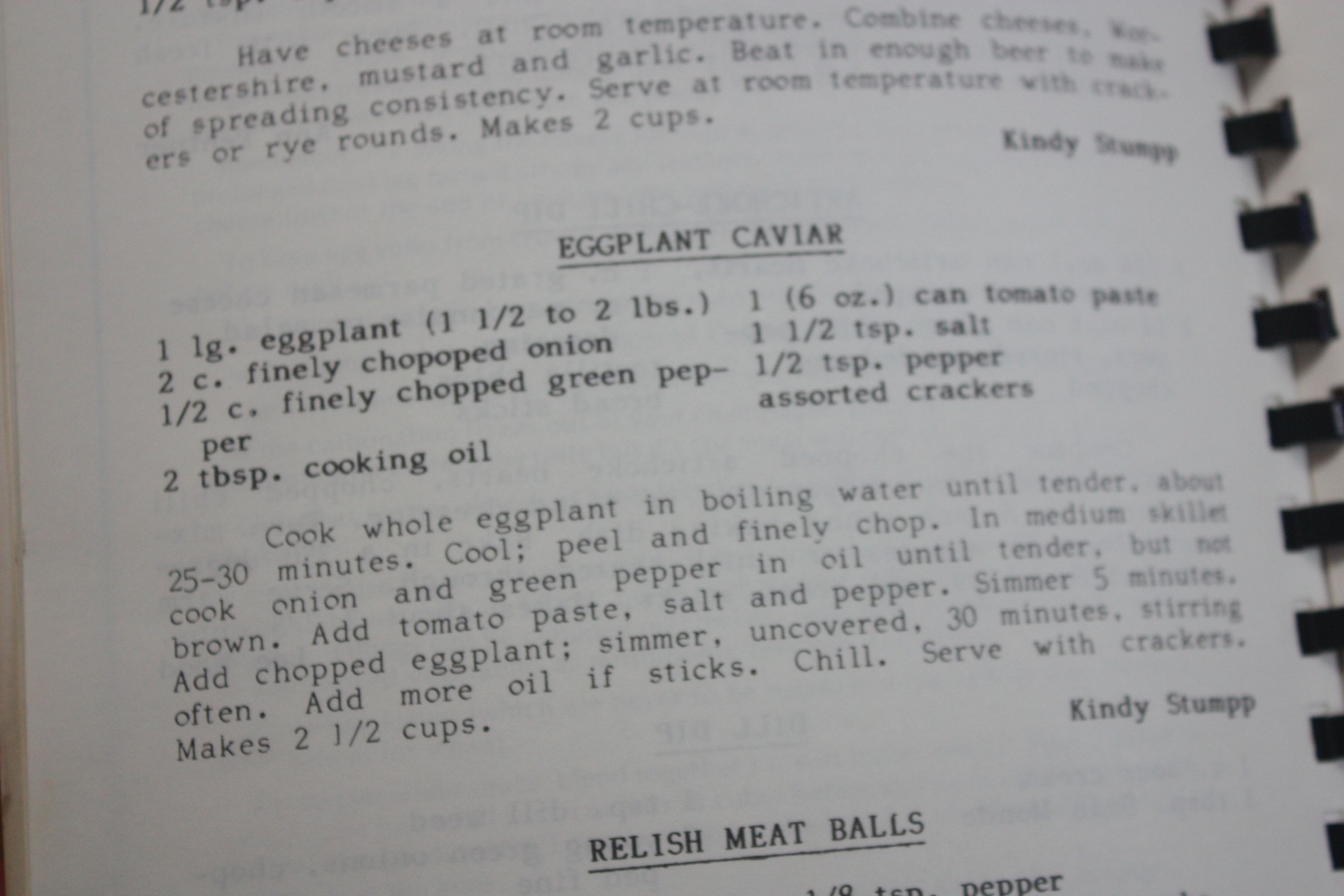

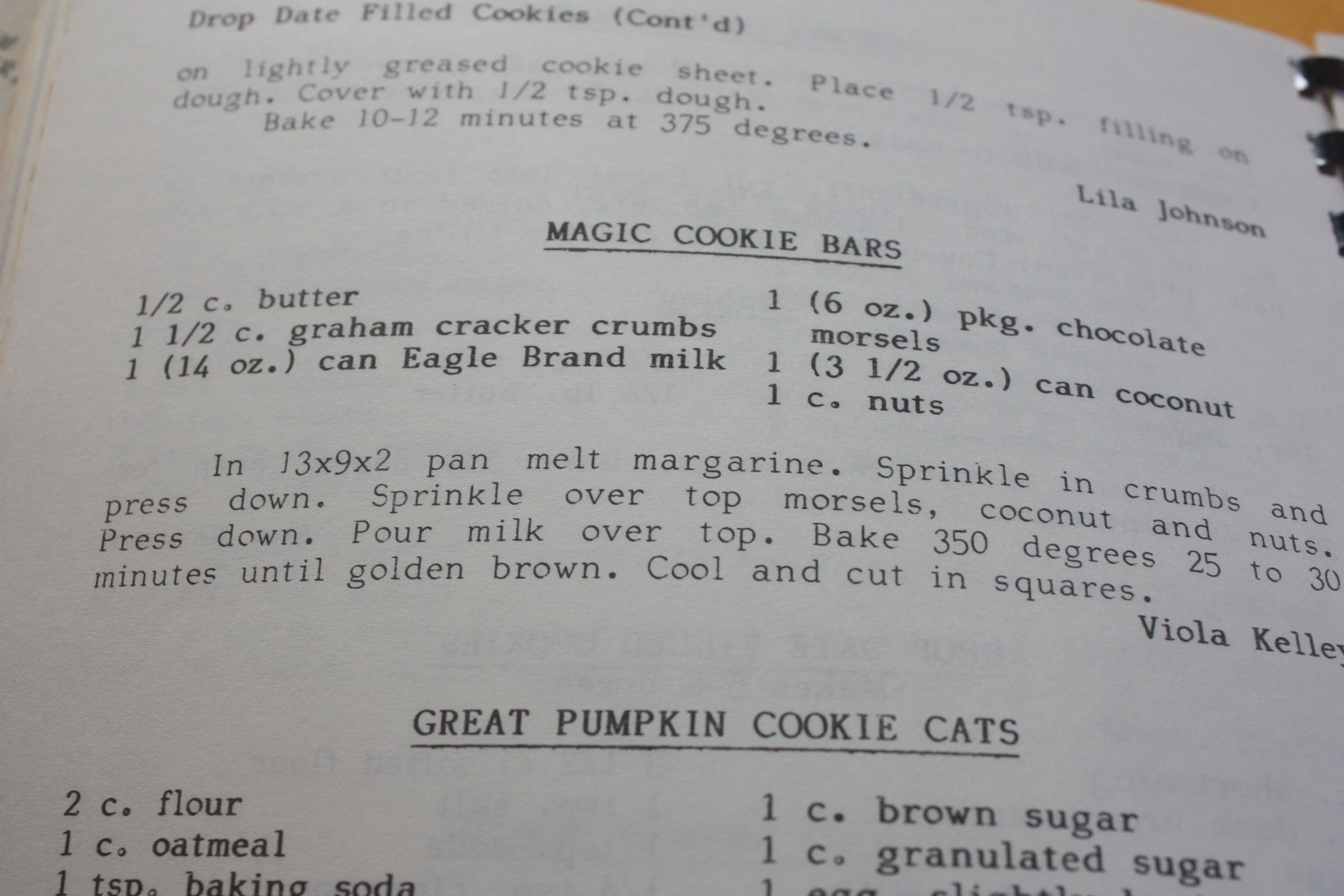

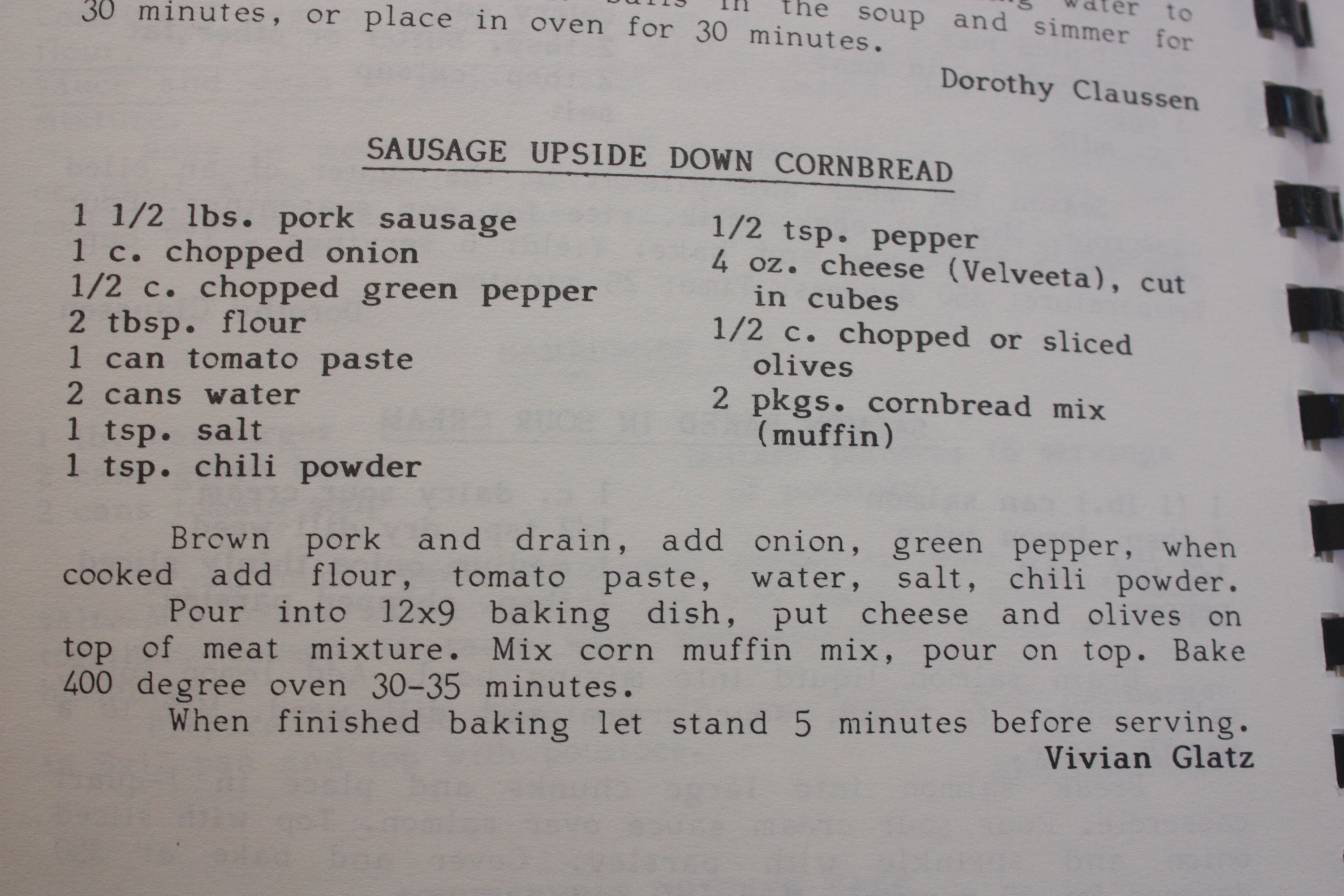

These old cookbooks were not about fancy cuisine. The churchwomen weren’t concerned with farm-to-table ingredients or organic food. They aimed lower: easy-to-make survival recipes, from a time when the woman of the house had to turn out a big hot meal every day in an hour or less in a time of no microwave ovens. Some of the recipes originally came off the back of a box or a can but were tweaked over the years. Or, not.

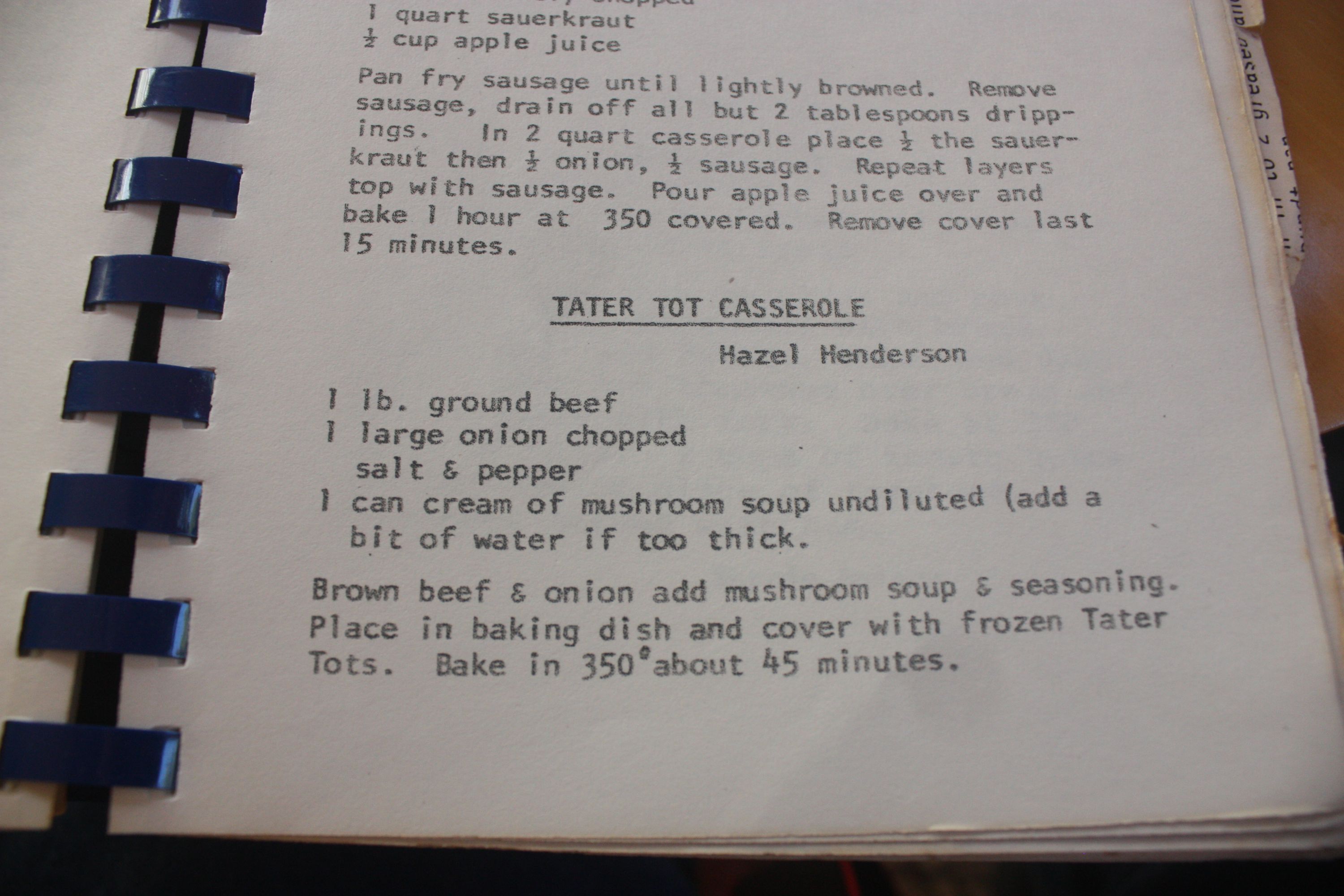

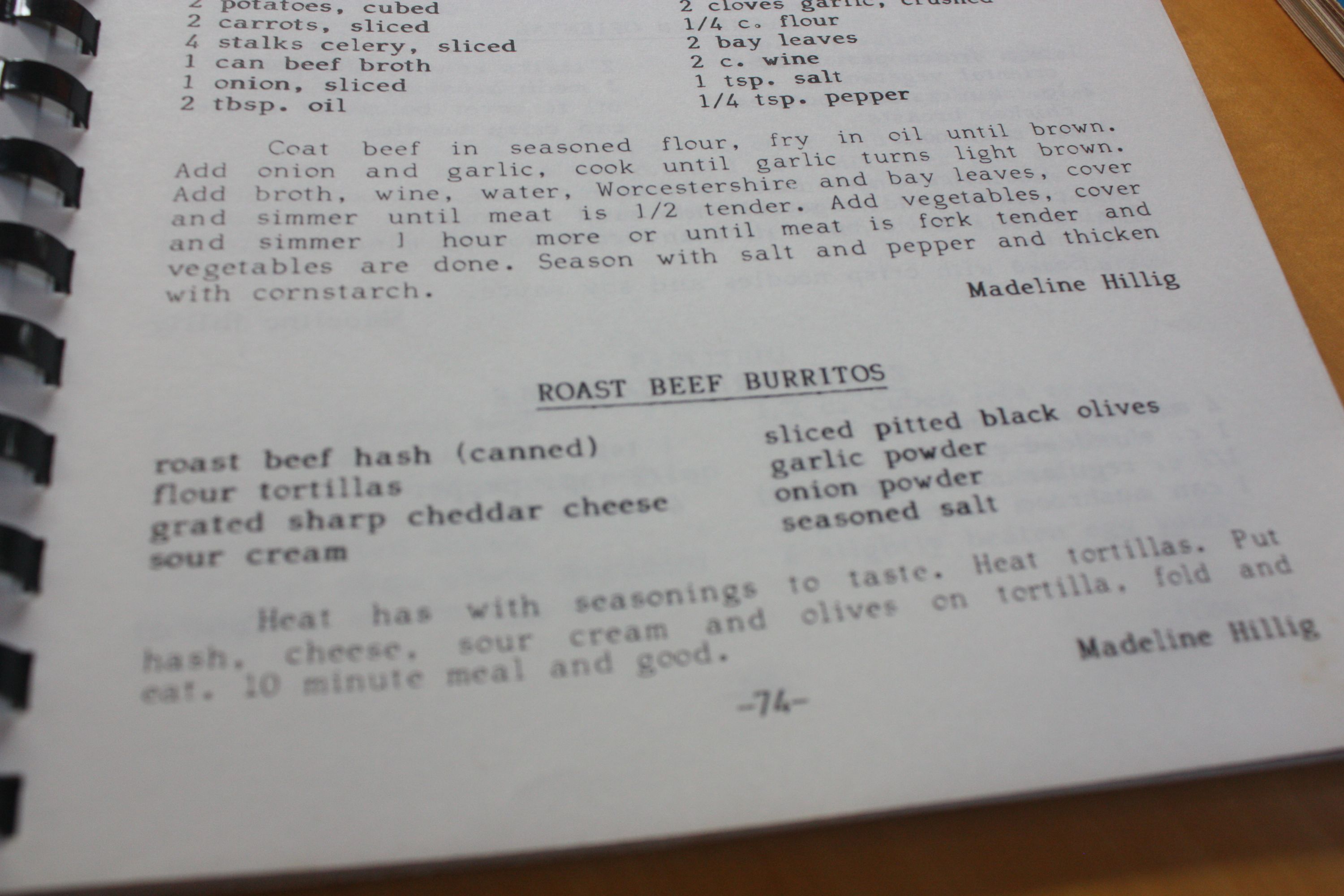

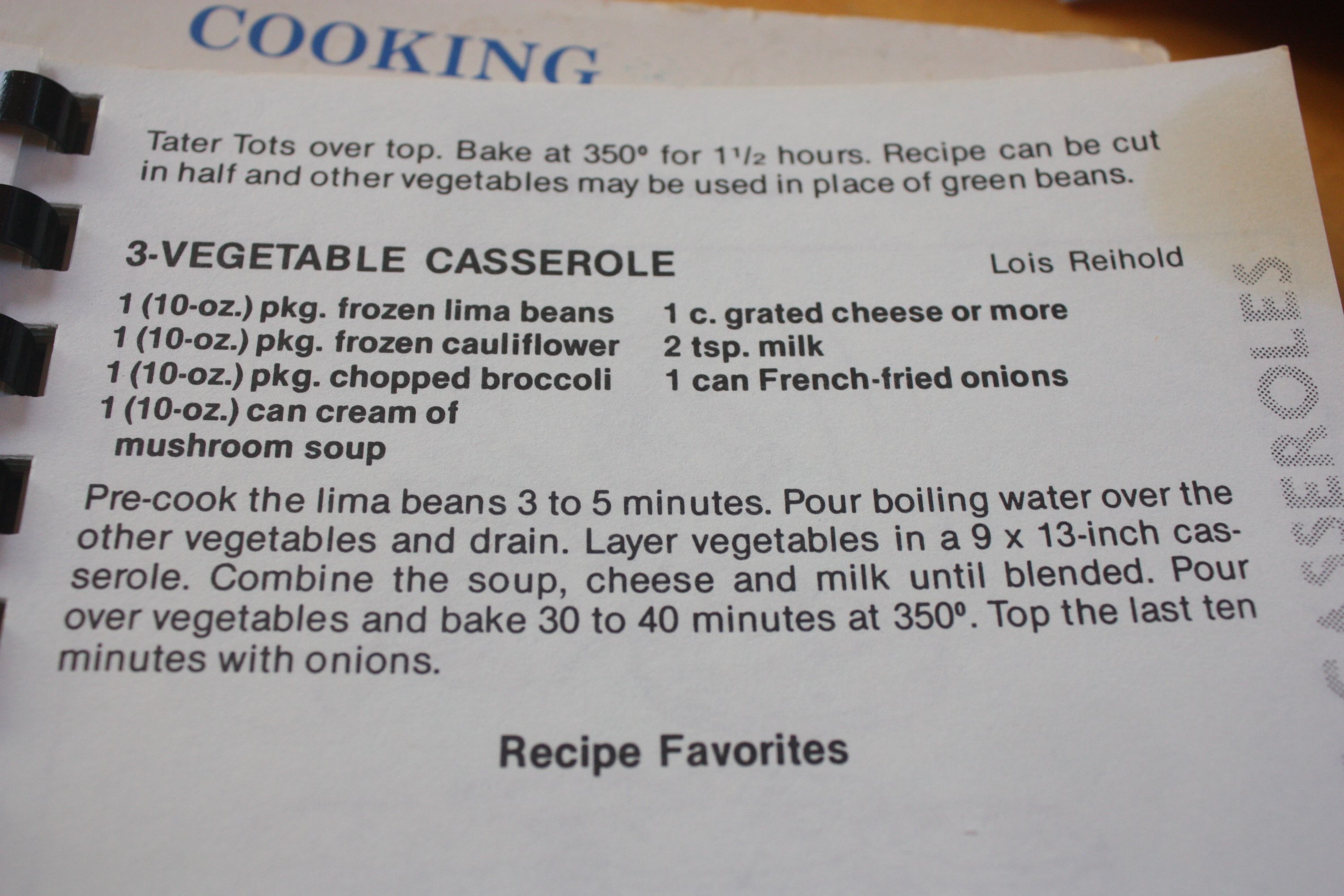

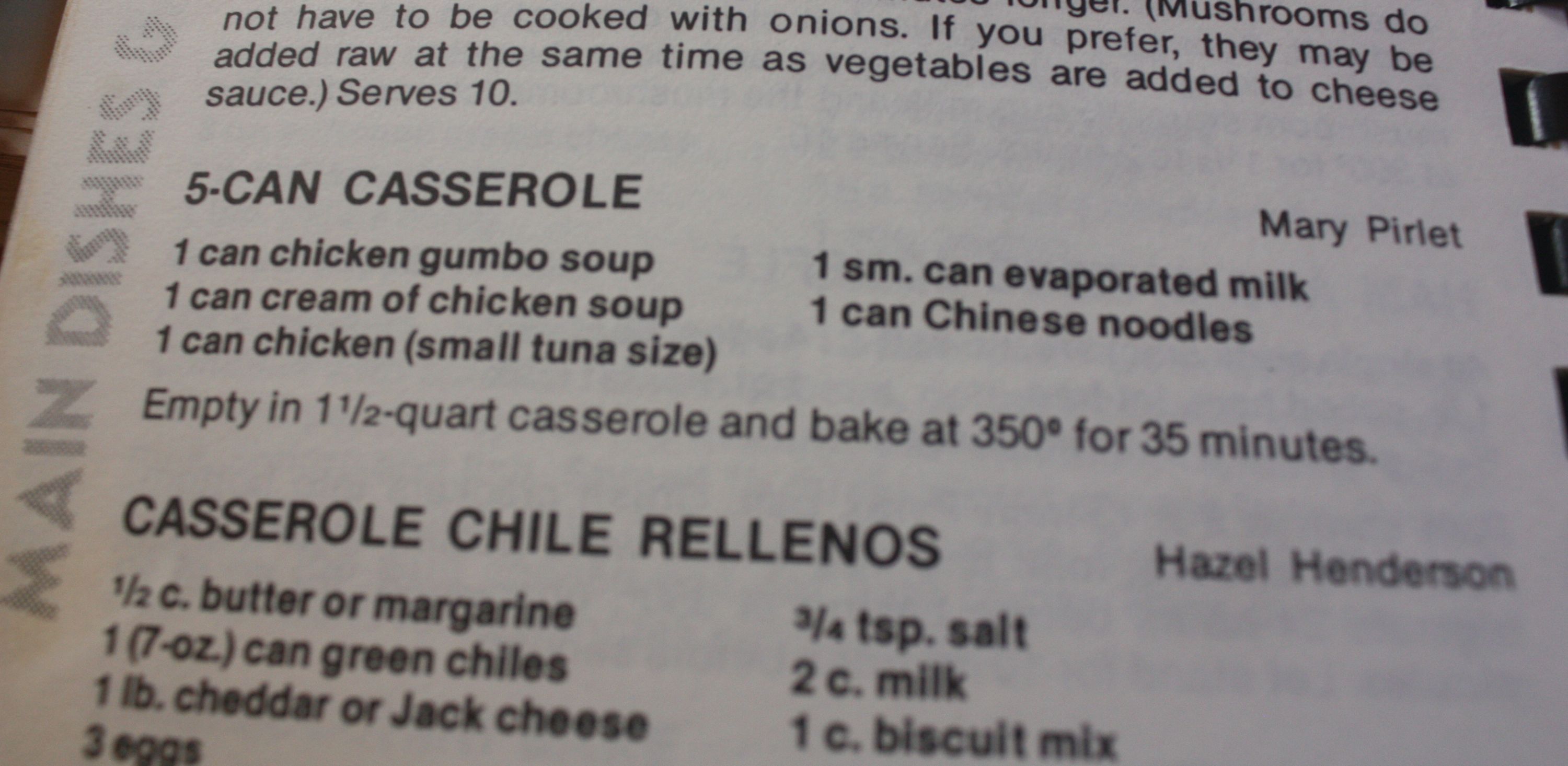

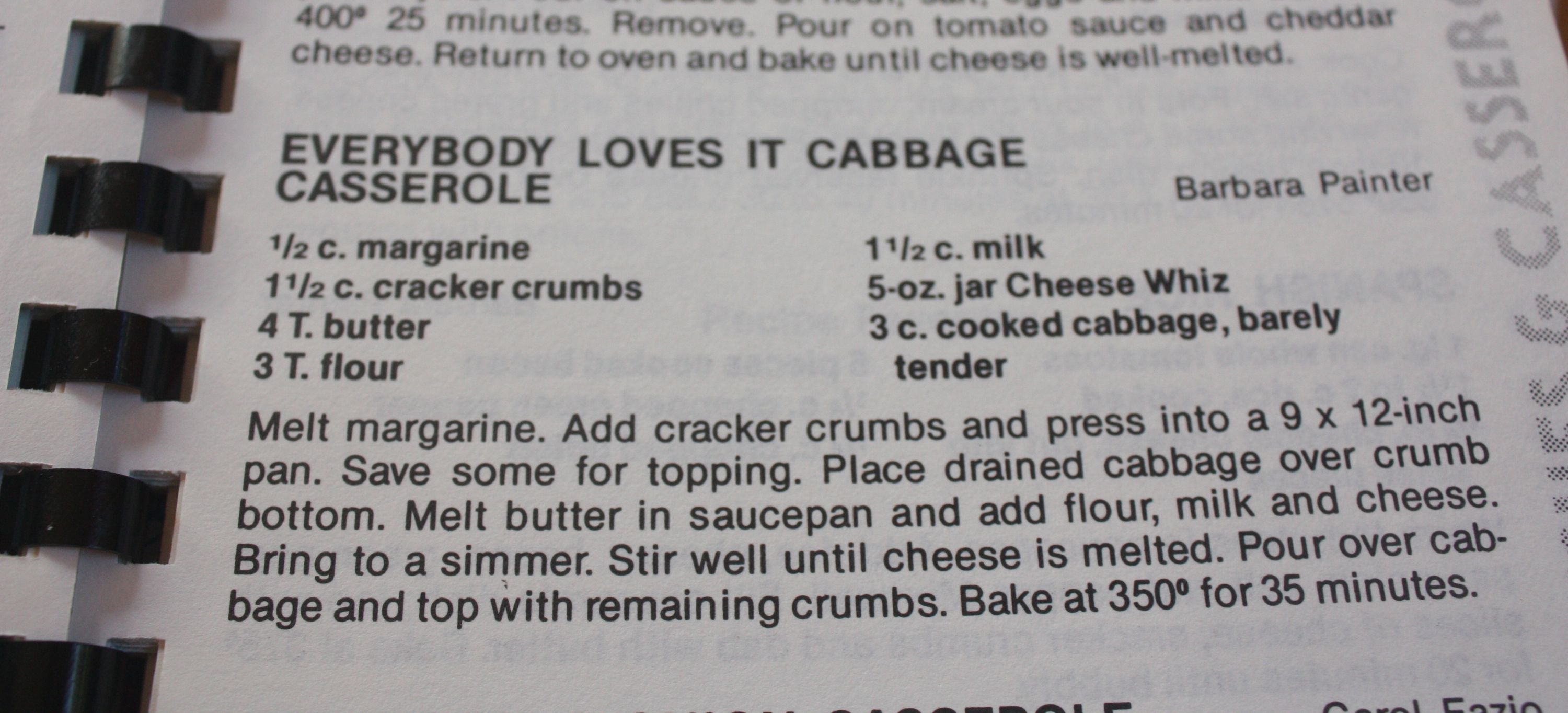

And they used pre-packaged ingredients with wild abandon, sometimes two or three in the sam recipe: cream of mushroom soup; dry onion soup mix; Bisquick; Jello; Hormel Chili; Velveeta. Cheez Whiz. Miracle Whip. Canned Chinese noodles. Mayonnaise by the cup measure, sour cream by the pint.

And that’s why people laugh at church cookbooks. “How could anybody eat that stuff?” they giggle, amazed. Well, we did, and many do today. But I understand. The first time I picked up a church cookbook the page fell open to a salad recipe that proposed nearly inconceivable operations on innocent packs of Jello. I couldn’t believe it.

Home cooks in the time of the nuclear family were the hackers of their day. They all had tricks for getting the food on the table quick and easy; or a special recipe for molasses cake handed down from some venerable matriarch, or a fried pastry dish from the old country. And the neighbor women had eaten them all, and wanted to cook them, too. Information passed from kitchen to kitchen on notepaper, the backs of envelopes. And in church cookbooks.

And you might ask, why? Decades ago, most of the housewives who made these meals didn’t have to work. They stayed home and kept house. They had all day to cook, right? Why the need for a hasty meal of canned roast beef hash burritos?

A lot of women had jobs even then, frankly; and they had to work and field a full meal every day, most of them. For better or worse, it was expected. And even the women who had no jobs, worked plenty, thank you.

My mother’s generation of home makers did a lot beyond keeping house and raising brats; not that this wasn’t hard enough. They took care of their own parents, who usually lived nearby: took them to the doctor, worked the bureaucracy for them, shopped for them, even took them into their homes. My grandmother spent the last 30 years of her life boarding with one son or daughter or another. She never saw an old folks’ home.

Housewives made the churches go; they took hot dishes to neighbors and fellow church members who were having a bad patch: illness, death in the family, a new baby. Sometimes they even took over the house chores for awhile.

And they ran Cub Scout and Brownie and Girl Scout meetings, the PTA and all those spaghetti-dinner fundraisers, Halloween and Christmas celebrations at the elementary schools, and supported the Little Leagues. My wife Rhumba went to a public theater school where volunteer mothers sewed all the costumes for every production.

And somebody had to write church cookbooks, and otherwise raise money for causes that taxes didn’t take care of.

My mother, who never went to high school, got her GED and trained as a beautician while raising two children and working at least some of the time. She didn’t stay too long in the beauty shop; but for decades after she did free permanent waves for all female relatives within twenty miles — and there were a lot of them. The stink of permanent wave solution filled the house; I can still smell it.

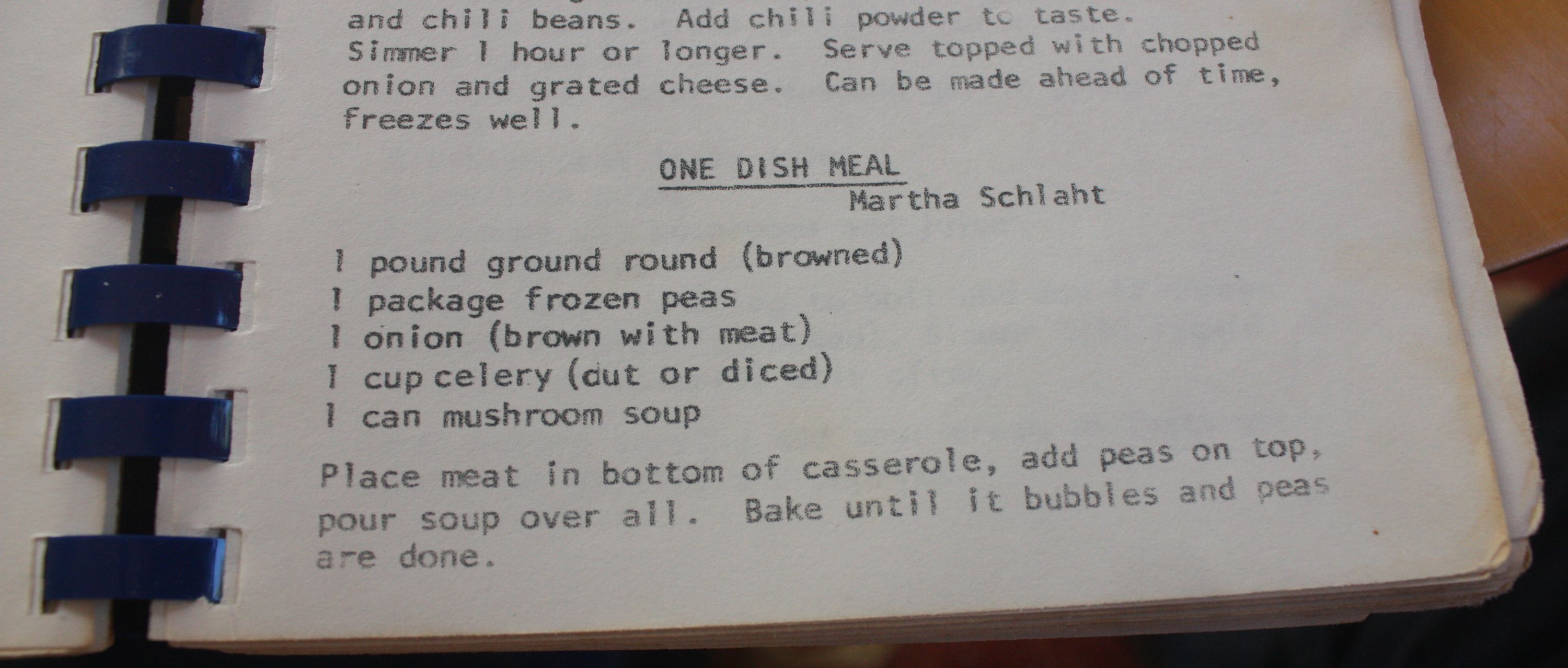

And when you’ve got a schedule like that, on some days a fast one-dish meal recipe from a spiral-bound cookbook may be all you have time for. They may even be named “One Dish Meal” for convenience. And sometimes there will be a felicitous bit of poetry on the ingredient list: “1 pound ground round (browned).”

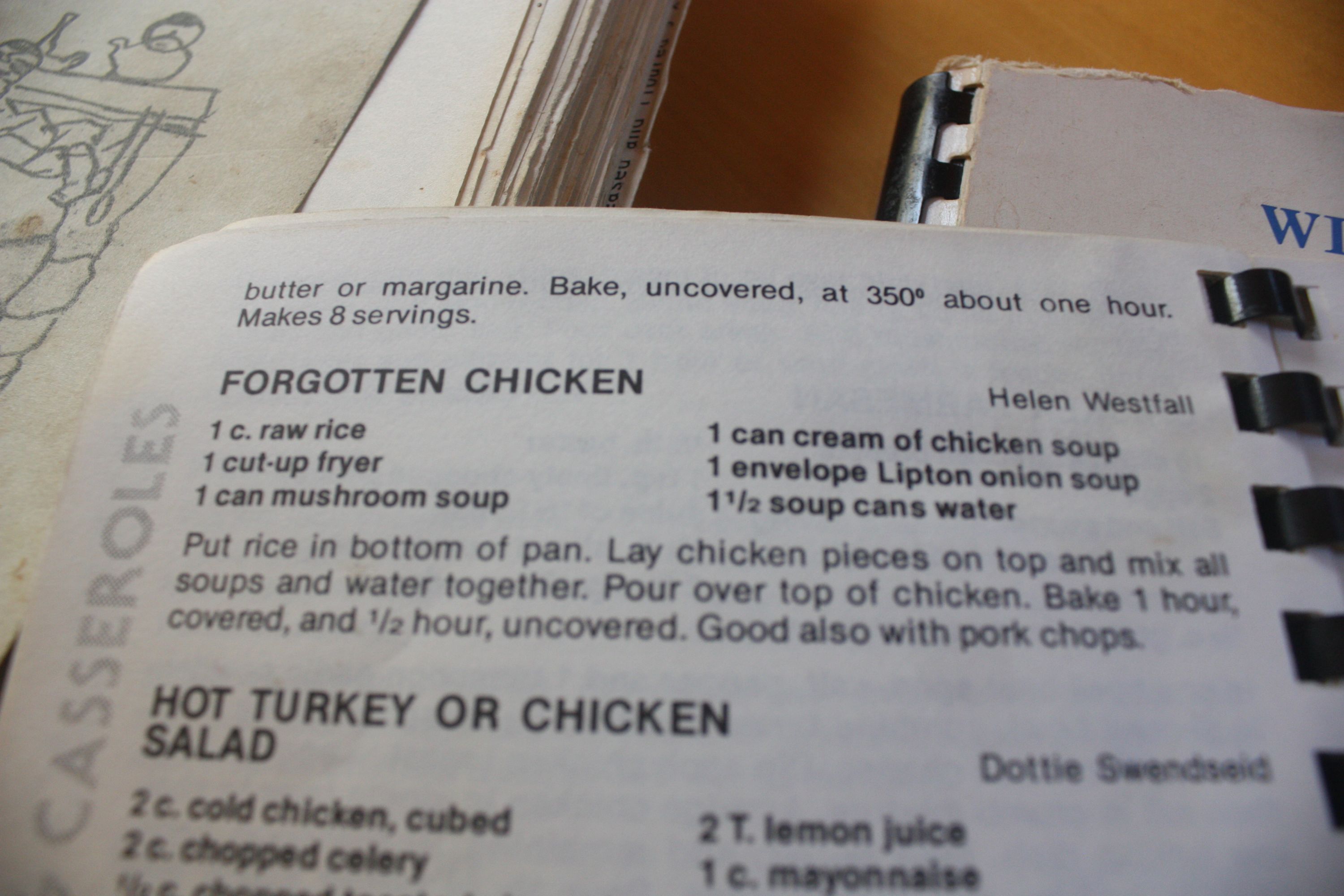

And there was the Recipe of a Thousand Names. It came from somewhere, probably off the back of a box, but millions of housewives gave it their own name and made it their own: chicken pieces on a bed of minute rice mixed with cream o’ mushroom and a pack of dry onion soup. One of my new cookbooks calls it Forgotten Chicken, because you dumped all the ingredients in a pan — literally — threw it in the over and forgot it for an hour while you cleaned the bathroom. A full dinner, with a piquant chemical tang from the dried onion soup. And foolproof: impossible to screw up. I even made it for myself when I went off on my own.

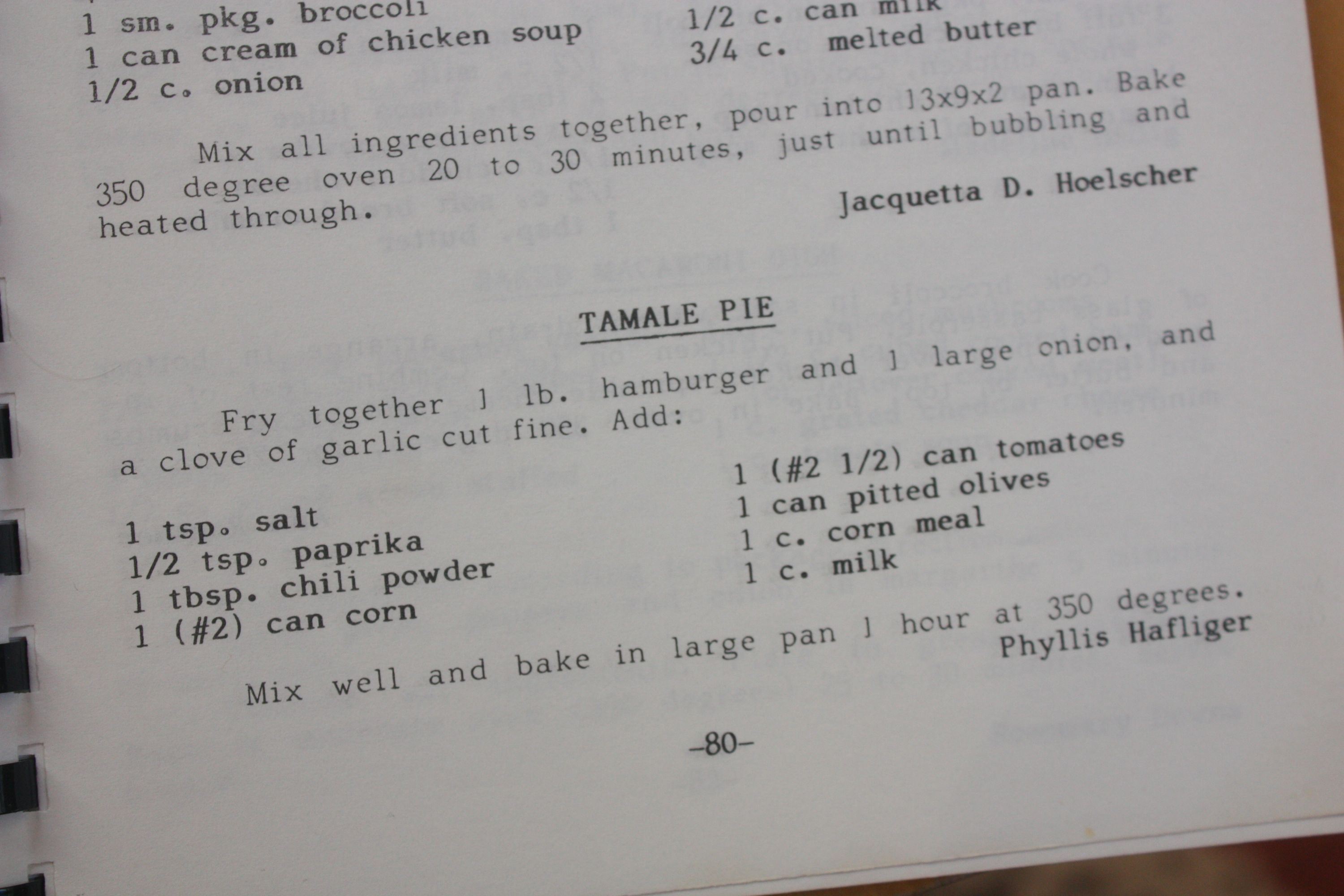

I must admit, church cookbook cookery wasn’t always wonderfully good. My mother’s favorite go-to emergency dishes were either spaghetti with meat sauce (welcome, because she’d make garlic bread, too) or the dreaded tamale pie with its huge, soggy chunks of bland, over-cooked corn meal. I’d hunt through them desperately for a string of cheese or the occasional olive; anything that had actual taste.

I don’t miss tamale pie. But I do miss community cookbooks; you don’t see many new ones anymore. Oh, the Junior Leagues and Symphony Societies still issue cookbooks. The pictures are color, the layout is impeccable. And the recipes are all gourmet, for a well-heeled audience who has time for those things.

But the down and dirty community cookbooks of yore are an endangered species. Everybody works; few people cook. And there’s the microwave and its attendant frozen entrees, or $11.99 “family dinners” from KFC, or cheap pizzas from Little Caesar’s. Or dinner out at (shudder) Applebee’s.

A rude surprise, wasn’t it: that in the ’70s women were finally fully accepted in the workplace. And within a few years, with the decline in blue collar work for men, they had no choice but to be there.

With women’s contributions, the household’s nominal income stayed even, for a while. But all the services that had been done at home, now how to be paid for. Nutrition has been outsourced. As has elder care, child care, transportation, youth groups and youth activities. Private industry does them now, and badly; and you pay, often through the nose

And I’ll say this: as appalling as some of those old recipes seem, we kids did okay on them. They raised a generation of children who largely weren’t obese, diabetic, or ill. And they were money-savers, many of them. That was always important, even in the supposedly fat ’60s.

And there were vegetables, because our parents came with a time when people were stunted by poor nutrition and their kids weren’t going back there, by God. Even if the vegetables were cabbage leaves coated with a strange Velveeta cheese mixture.

And now corporations provide the food, at high price, low nutrition with artificial ingredients, all marketed to our own worst instincts. And with full knowledge of its harmful effects. And once again, children are stunted by poor nutrition: not by insufficient food, but by too much, and of the wrong sort.

And now corporations provide the food, at high price, low nutrition with artificial ingredients, all marketed to our own worst instincts. And with full knowledge of its harmful effects. And once again, children are stunted by poor nutrition: not by insufficient food, but by too much, and of the wrong sort.

I’m not arguing for women to head back to the kitchen. Nobody should be trapped there by gender or for any other reason. What I do want is for the services for our private lives to be ripped from the hands of “investors” and handed back to us, the private citizens and our special creativity.

That would mean a guaranteed income. That would mean a fair division of the fruits of the economy to the point where all citizens have enough time and flexibility to fulfill the ultimate purpose of civilization: the endless enrichment of the lives of all its members, by all of its members. Long lives. Healthy lives. Lives full of richness and empty of fear.

And maybe even, some day, more church and community cookbooks. Anybody up for Chili-Ghetti Casserole?