Every Saturday I hit the neighborhood Goodwill thrift store for a good look-round. There’s much to find; wealthy areas have the best thrift stores, and in the aggregate this city is pretty wealthy. Though the swag’s not a patch on what it was seven or eight years ago when you could score a two-hundred-buck Aran wool sweater for $3.75. Sometimes I miss the housing bubble.

Yes, we’re wealthy here in the aggregate, but less so in the particular. Living costs are high. Respectable citizens like myself routinely shop Goodwill, to stretch those precious dollars. But we don’t socialize; when I spot an acquaintance, they rarely want to talk. They seem uncomfortable, as if I’ve learned something I’m not supposed to know.

And yet today, somebody tapped me on the shoulder and asked, “Can you help me with something?”

I turned to face a lean, older, African-American woman in a gray pants-suit. She pushed a shopping cart; in it she’d laid out a man’s gray suit with several shirts and ties.

“I’ve been here for two hours, and I can’t make up my mind,” she said with some frustration. “I’m putting together an outfit for my husband to wear for when my daughter comes home from India next week. Can you help me pick the shirt and tie?”

Why do these things happen to me? I have barely the awareness to walk in a straight line, but on occasion total strangers will pick me out of a crowd to ask for life advice. Or directions on getting to Highway 17. Life advice is the easier of the two.

And today I wore faded denims and a Dickees cop windbreaker. Hello, Mr. Fashion Maven.

The woman had not a lined face so much as one of cords; cords moved in her cheeks, her neck, her wrists. Her suit was neat, but older and well-used; she’d probably bought it here. She looked to me like a decent person who’d worked hard all her life for not a lot of money, and never complained. But felt that a little help wasn’t too much to ask.

It wasn’t. I’m good with colors. I’m partially color-blind, and I’m good with colors. Go figure; but my wife rarely makes color choices without checking with me.

The suit was deep gray; not ultra-dark, but rich. Maybe a little blue to it. A good choice. All three long-sleeved shirts were also shades of blue, ranging from washed-out sky-blue to a medium sapphire. The sapphire was one of those thick-fabric non-wrinkle jobs; it retained its body, even used. The others were limp.

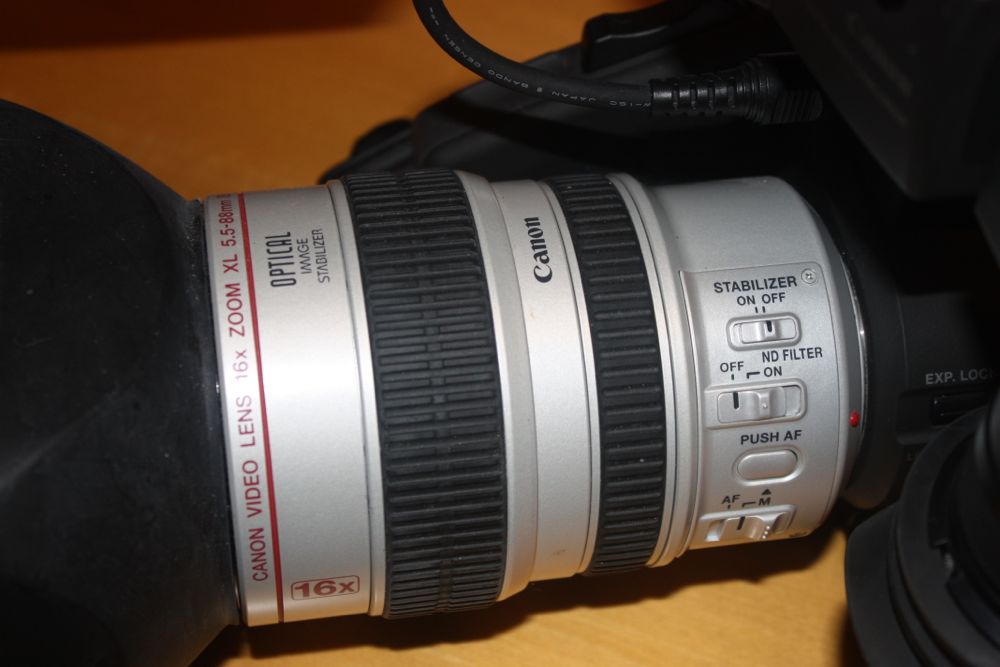

“The dark blue,” I said, meaning the sapphire. “But none of these ties work. You need one with blue in it. The greens and yellows don’t match the shirt.” Each tie included a bit of grey; she’d matched them to the suit. But they weren’t the right grays. And in any case, you can’t omit the shirt from the equation.

“I’ll come back with more ties,” she said decisively.

“I’m not going anywhere.” I’d been working my way down a 20-foot rack of t-shirts.

I felt confident about the shirt; dark-skinned and olive-skinned people like her family and myself look good in strong colors. It’s you pale people who favor earth tones, blacks, and pastels.

“So, is your daughter on some educational trip?” Trip, India, homecoming: I was trying to make sense of it.

“Yes, she’s a business student, and she went to India for her studies.” The woman looked like she had the means to maybe send a daughter to St. Louis.

“She’s coming home, and I want my husband to be in a suit to greet her,” she said. “She’ll be so surprised. Because usually he dresses sort of Santa Cruz.”

She wanted her daughter’s home-coming to be special. Santa Cruz is the name of our town, a casual seaside community. “Dressing Santa Cruz” means that you think a t-shirt and denims will do for an anniversary dinner at Le Haute Spot. And, if the weather’s cold, an O’Neil hoodie. I neither joke nor exaggerate.

The woman left, and returned promptly with several ties that were less ghastly — marginally. I chose a faded tie that had at least some blue in it, though not a shade that especially matched the shirt. Still, it could work.

The woman in gray thanked me, and went her way. I had questions, but let them lie. So I made purchases and, without meaning to, walked out the front door just as the woman did. Night had fallen with a thud; and we both turned into the same dark alley. My home and her car lay past the other end. I unlimbered a flashlight and offered to escort her.

And, given another chance, I asked my questions:

“So, where does your daughter go to school?”

“Stanford.” Whoa. The rich kid’s school. Yet they’re not shy with scholarships for exceptional students of any price range. The upper echelons of society can always use fresh blood — in small doses.

Stanford’s still quite a leap for a family of modest means. But it seems that Daughter was sharp as a tack (“She got her first ‘B’ at Stanford,” her mother told me) and had applied for every scholarship in the universe.

And so Daughter’s graduating in spring with a master’s degree in business — $50,000 in debt. Strangely, that’s not bad at all. Recruiters are eager for Stanford MBAs. The daughter will leave school to face a vast row of open doors. She’ll know a lot of things — and a lot of people who can help her. Doors could open for her all her life.

“Well, there’s nothing like a full ride scholarship,” I said to her mother.

“There’s a full ride, but plenty to pay for besides,” she answered. “And we’ve been paying it.”

We got out of the alley and back into the light, and went our separate ways. I wish her well.

I really do. Because her daughter’s story reminded me of a friend who’d gone to Stanford, too, forty years ago. He, too, was of modest background. He, too, bucked the odds. His name was Mike Garcia.

Mike’s parents and mine were friends, so I spent a lot of time with him and his three brothers. Mike was the only one I could stand; we had a lot in common, but he was the improved version: better-spoken, more confident, more physically able, gifted in both the sciences and the creative arts.

And he dreamed big. Mike was the kid who went to Europe as an exchange student. Mike was the high school class valedictorian. And, somehow, though his family had no money, Mike was going to become a doctor.

And he did. He earned a full-ride scholarship to Stanford, where he majored in chemistry and hob-knobbed with the children of the wealthy, the famous, and convicted Watergate conspirators. That’s Stanford.

But because he was exceptional, and frankly very likable, Stanford took care of him; among other things, it got him jobs on campus and summer work that paid the rest of his expenses. When Mike graduated, he joined the military; it has its own medical school. He got in. He graduated, then interned. He became an officer and a doctor.

I’ve omitted one fact: Mike was gay. He never really came out, certainly not to me. He discretely navigated his sexuality through Stanford, into the military, and through medical school. And then, out the other side and living off base, he felt that it was time to be himself.

And it was the early ’80s, and he was himself with a partner with AIDS, before AIDS was widely understood. Mike died relatively quickly. The military was civilized about it; perhaps more civilized that they would be later.

And what does this have to do with a hard-working woman of modest means who’s putting together a celebration for her own brilliant child? Who plans to stuff her slovenly husband into a Goodwill suit just to make it clear to her daughter how much they both love and care for her? And whose husband probably will let her?

This has nothing to do with that woman. But it has everything to do with her daughter. Her daughter may come to move among the elite in America. She may meet and work with people whose names the newspapers venerate as geniuses, as movers and shakers. She may become one of them. She may come to believe that talent and hard work are all it takes for anyone to rise to the top. So she’ll be told by the other people who inhabit society’s lofty peaks.

And if she does believe that, she will be wrong. It’s luck.

The luck of the draw for parents, resources, contacts, school, physical ailments, a million things. Mike’s luck ran out, disastrously; but he went as far as he did thanks at least in part to an exceptional public high school: heavily subsidized by the paternalistic company that dominated the town’s economy.

The daughter of the woman in gray got good genes and talent. But where would she have gone without the kind of parents she has? Without that exceptional woman, and her husband, who gave her the values of hard work and persistence and study? And beyond that, gave whatever money they could raise to get their gifted daughter into the nation’s hottest business school? That daughter is her own person; but equally, she is her parents’ achievement.

So why didn’t the woman in the gray suit go as far in life as her daughter did? Good question; but if genes, hard work and grit alone were all it ever took to reach the top, I’d be watching her on TV. And George W. Bush would be a small-town insurance agent attending AA meetings and working on his third marriage.

I hope that her daughter knows this. And knows that she will never find, among any future cohorts of the mighty, a person more worthy or exceptional than her mother, the woman in gray who flagged me down in the t-shirt aisle of a thrift store for the use of my fashion sense.

There remains Mike, the ghost raised in that aisle after so many years of silence. Mike, who’d done everything right, as it’d been explained to him; who only wanted what other people had, and didn’t understand what he was risking. We are all Mike.

For Mike, to the young woman, and to her mother, I include a stanza from a poem that I’ve always respected. Nothing in it, I expect, would be news to the woman in gray.

Therefore, since the world has still

Much good, but much less good than ill,

And while the sun and moon endure

Luck’s a chance, but trouble’s sure,

I’d face it as a wise man would,

And train for ill and not for good.

’Tis true, the stuff I bring for sale

Is not so brisk a brew as ale:

Out of a stem that scored the hand

I wrung it in a weary land.

But take it: if the smack is sour,

The better for the embittered hour;

It should do good to heart and head

When your soul is in my soul’s stead;

And I will friend you, if I may,

In the dark and cloudy day.