Rarely does a single football play earn a t-shirt of its own. But The Play is not just any play. It is the play, the wildest college football play of all time: in which the Big Game between two rival universities devolved into madness with four seconds left on the clock.

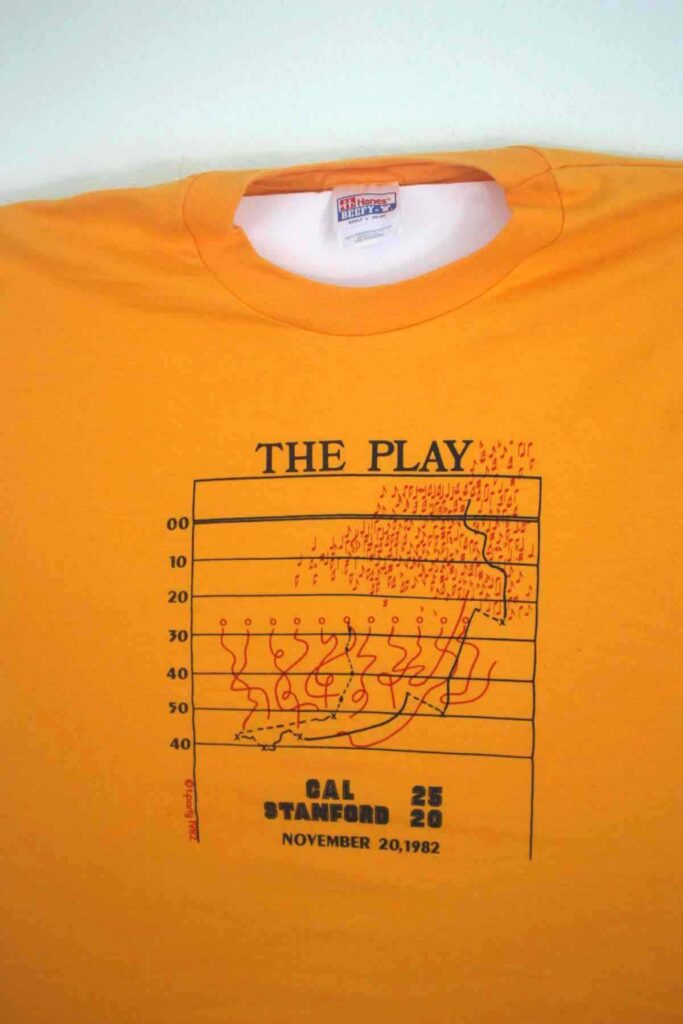

Take a look at the chart. It shows the zig-zag path of ball carriers for one team up the field to the other team’s end zone. That path cuts straight through a mysterious cloud of dots. The dots represent a marching band that had wandered onto the field.

It all took place on in 1982 but in the minds of college football fans it was only yesterday. They still argue about it.

The Big Game: that’s what they call the annual football game between the two leading universities of the San Francisco Bay Area: the University of California at Berkeley (“Cal”) Bears, a public research university of great esteem; and across the Bay in Palo Alto, the Leland Stanford Junior University (“Stanford”) Cardinal, a wealthy private research university that is well-known as the rich kid’s school.

Berkeley you’ve heard about. As for Stanford: a friend of mine went there on scholarship in the ‘70s and hob-nobbed with children of convicted Watergate conspirators from the Nixon administration. You get the idea. The two schools are not sympatico, have always been rivals.

So there’s a certain intense and primal relationship there. By November 20, 1982, the Big Game between Cal and Stanford had been ongoing for over 80 years. Winner claimed the trophy — the Stanford Axe — until defeated by the other team in a future year’s Big Game. But on that day in 1982, there was much more on the line.

Bowl game season was coming. The Cal Bears’ many wins that year more than qualified them for a bowl game — but no one wanted them. The Stanford Cardinal, with only a 5-5 season but some good wins, had a bowl game waiting for it. All the Bears had to do was win the Big Game. Then they would qualify. All Cal had to do was stop them from doing it.

And it was a hard-fought game. Cal maintained a lead through the first half, but Stanford came back in the second. The lead moved back and forth all the way to the end. With Cal ahead 19-17 and only a few seconds left, Stanford jumped ahead 20-19 on a field goal. Stanford had left extra time on the clock in case a second field goal attempt was needed. But it wasn’t. So four seconds remained for one more play: a kickoff from Stanford to Cal.

Circumstances turned odd even before the kickoff. When Stanford had scored the field goal, additional team-members and supporters illegally stormed onto the field to celebrate and earned a penalty for the team. This penalty required Stanford to kick off from their 25 yard line, not at their 40 yard line as usual.

And they did. Cal received the kick on their own 45 yard line. Under pressure from Stanford defenders, the Cal player who received the ball made a lateral pass to another Cal player. That player got into trouble quickly and laterally to yet another Cal player named Dwight Garner who ran a few yards and was tackled by five more Stanford defenders. But before he went down, Garner pitched the ball back to the original receiver.

It wasn’t clear to Stanford fans that Garner had gotten the ball off before he was tackled. They thought the game was over and that Stanford had won . The Stanford Band, 144-strong and primed for victory, charged out onto the field in front of the Stanford end-zone to begin the celebration, along with cheerleaders and Stanford players who ram onto the field illegally (again).

Meanwhile, the Cal ball carriers lateralled their way toward the madness, keeping the ball one step ahead of the Stanford defenders. The final carrier received the precious spheroid on the Stanford 25-yard line; he ran full tilt through the Stanford band and creamed a trombone player on his way to the end zone and a touchdown.

Cal had won! Or had it? The refs hadn’t made the call yet.

The men in black and white huddled briefly. A couple of the lateral passes might have been illegal, especially the last lateral; but they couldn’t see it clearly. The Stanford Band had blocked their view. And the band’s appearance on the field (along with additional Stanford players) was definitely illegal interference anyway: conceivably the refs could have given the game to Cal for that alone. But… Cal had scored on the play.

The head ref made his decision. He stood up and faced the crowd. Everything went silent. Everything. Then the ref signalled in favor of Cal. And, in his own words, “I thought I had started World War III; it was like an atomic bomb going off.”

Up above the action, the Cal radio announcer shoved his microphone down his own throat and began eating it. You want to hear this performance (apparently slightly edited to leave out the pause for the refs). I didn’t know that the human voice could do these things.

So an emotional atomic bomb of sorts exploded that day. And like the blast from a real atomic bomb, the carnage from The Play went on and on. Was this right or wrong? The arguments never ceased.

The next year the Stanford Cardinal’s record amounted to a miserable one win and ten losses. No good players wanted to be associated with the team. The head coach lost his job.

The Stanford quarterback for The Play, John Elway, nursed a bitter grudge over The Play for decades, through an otherwise wildly successful pro football career that ended in the Hall of Fame. The Play “ruined my last game as a college football player” and his chance to take part in a college bowl.

But it was a great day to be a Cal fan. A great month. A great year. At the time I worked in an office building just a mile or so south of Berkeley off the Eastshore Freeway. A week or so after The Play, one of my co-workers came to work in the t-shirt that you see above.

He was a Cal alumni. In those days a t-shirt violated office dress code practically anywhere. But nobody had anything to express except admiration.

It was, after all, nearly Berkeley. And it was, first and foremost, The Play.