I am waiting for my sandwich at the only good deli in town. The front of the store opens to the outside; warm air wafts in on the sunshine. The weather is perfect: absolutely perfect. We get that around here. Actually, we get that a lot.

I have a paper slip with my order number on it. Near me, holding the same, stand two Cool Moms and their only slightly gawky teenaged sons: 19 years of age or so.

The mark of a Cool Mom is that, at first, she looks like her teenager’s sister. This requires a certain attitude, good genetics, time for diet and exercise, hair and skin care, and money to pay for.it all. You can read money on the boys, too: well over six feet, flawless skin with good color, perfect teeth.

Only through laughter do the Cool Moms prove that they’re moms after all. Their smooth faces crease into smile lines — as much a sign of experience as age. And then you notice that their skin isn’t quite so pudding-smooth as their children’s, and that their facial features are larger and better-defined.

The four of them settle at an outside table and chatter like school pals, relaxed with one another. My eyes turn to a middle-aged Leonard Nimoy, drinking artisan cherry soda at another table. He frowns down at a small blue book which, apparently, contains no pictures. There is no way for me to read the title; I so want to, though.

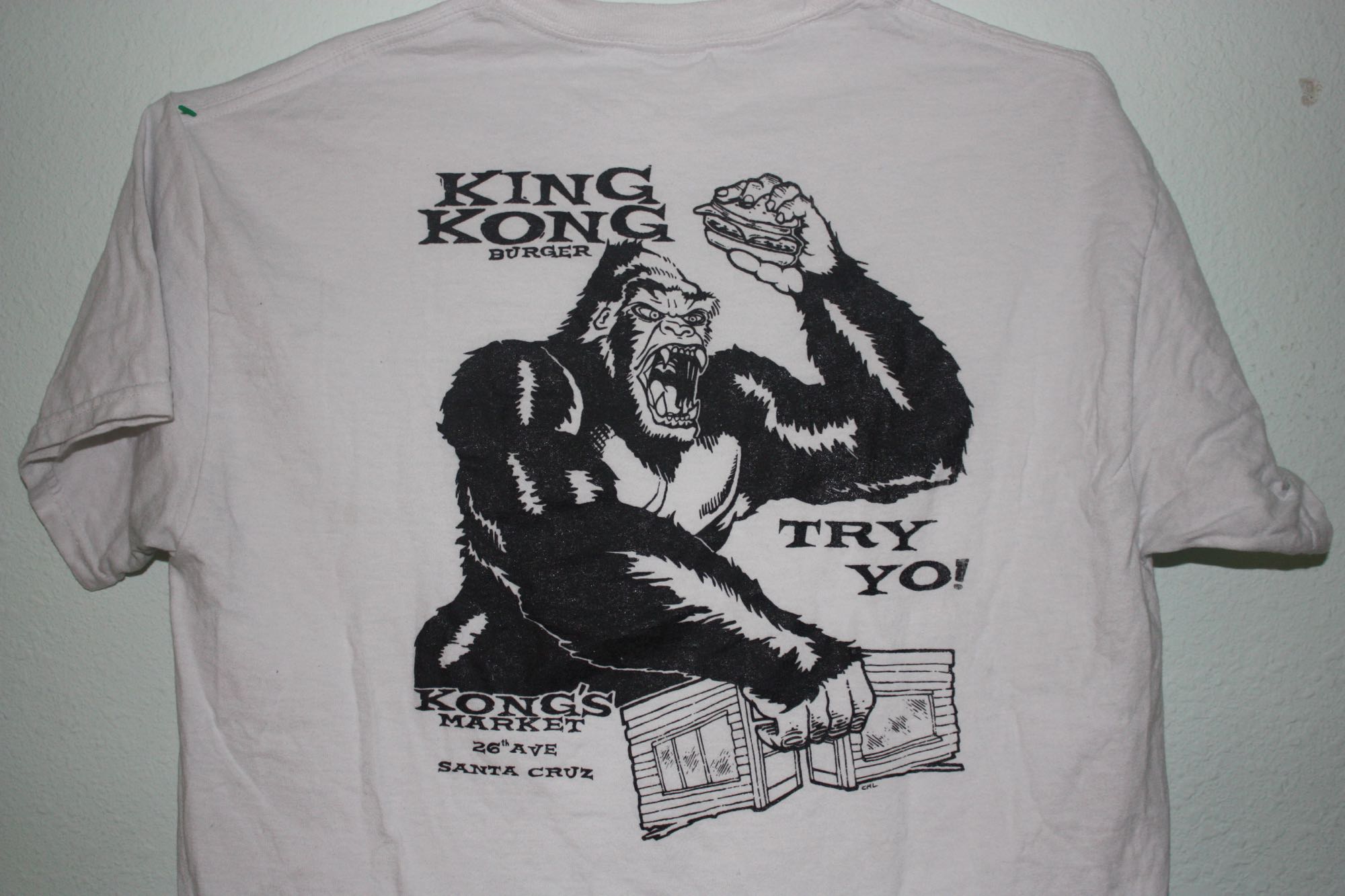

The street itself is calm. This is the downtown business district, but at 3 pm on a weekday most of the citizenry are stuffed away in concrete boxes doing things for a paycheck, here in town or 30 miles away in Silicon Valley. No sunshine and cherry soda for them. Meanwhile, a couple of muscle-bulging 50-somethings jog past the deli together. They have tattoos.

I am doing what I love most: people-watching, and telling myself stories about the people I watch. My wife Rhumba enjoys doing this with me, but she’s down the street buying a cheese slicer.

It’s only because of Rhumba that I can indulge myself on this fine afternoon: when I should be in my office slaving away at tasks that do not suit me. Rhumba is retiring from her job of many years, and we had to go to the Social Security office to sign up for Medicare B. Rhumba doesn’t drive, for a number of medical reasons.

Her co-workers never stop marveling at her imminent departure “It’s time for her to enjoy life!” one of them told us as we headed for the door. “What’s she going to do with all that time?” Apparently Rhumba’s empty schedule is a source of puzzlement.

They don’t take appointments down at SS, so we both took three hours off and hoped for the best. You know bureaucracy: lines; packed waiting rooms.

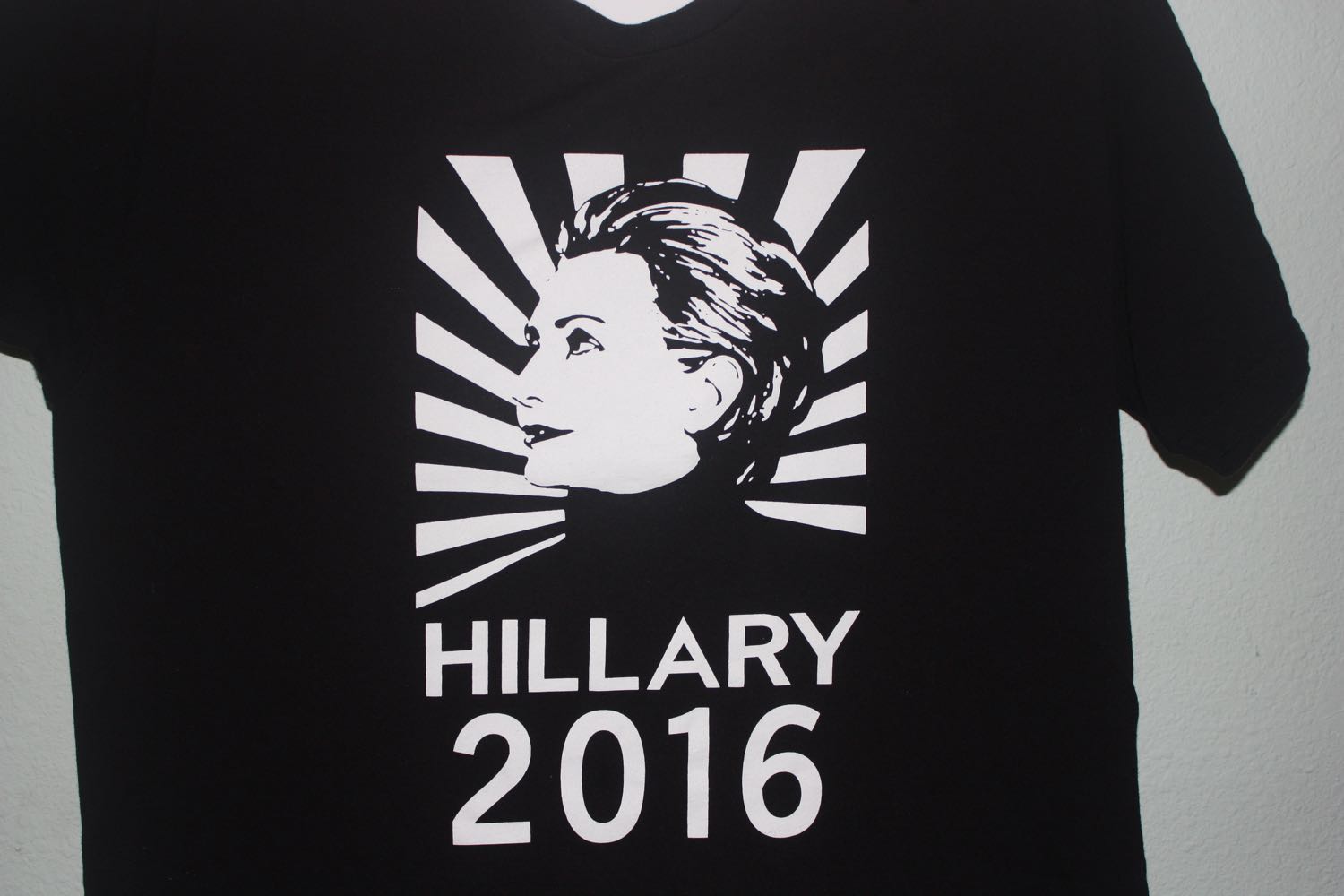

At least I though I did. When we got there, we found nothing but solitude: rows of empty waiting-room chairs, and not a worker in sight save the security guard. Cheaply-framed photos of President Trump and Vice President Pence hung on the wall, tilted slightly. They seemed ill at ease .

“Enter your name and social on the ticket machine, and it’ll give you a number,” the guard told Rhumba. She did; the machine spit out a ticket: number 135.

Instantly someone shouted, “Number 135!” A man popped up from behind a counter, grinning. And the paperwork began. Documents passed back and forth. The counter clerk could obviously do this in his sleep. He could probably grin in his sleep, too, because he never stopped.

Save for us, the office kept on being empty. “Did we pick some special, magic time to come here when no one else does?” I asked him

He shook his head. “It’s completely random.” He passed the final piece of paper, grinning of course. “There you go. Now you can enjoy life!”

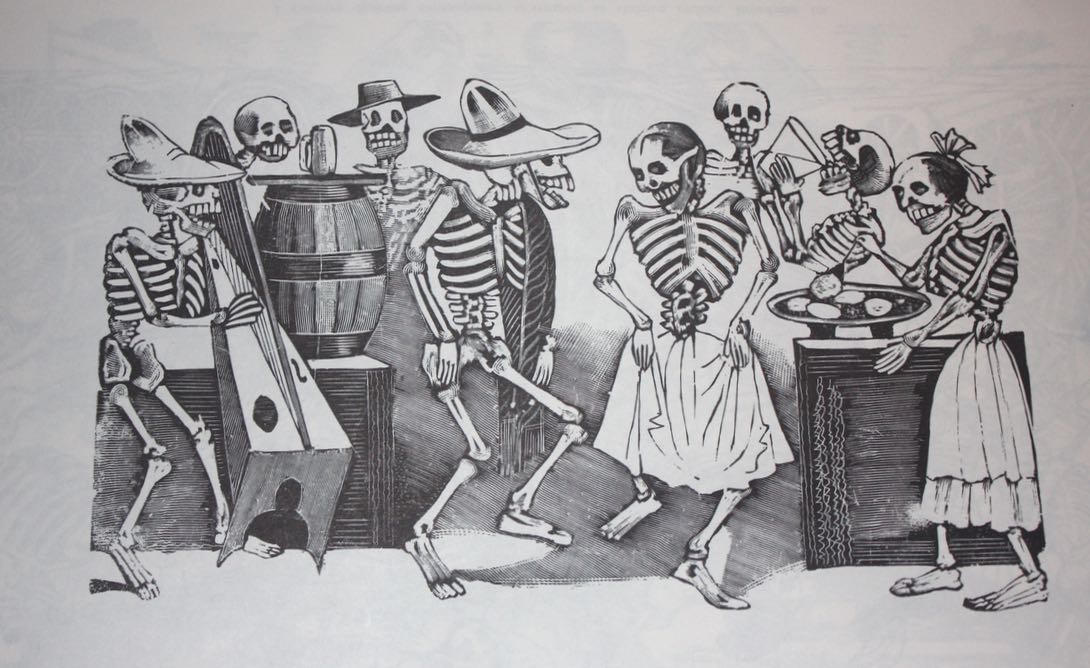

Ah yes, enjoy life. The golden years. I do wonder why most of us have to wait so many decades for them while we run to a schedule, doing tasks we don’t particularly care for and scrambling to pay bills.

All this, for the promise of a few years at the end doing what we want, while our powers of mind and body diminish. And while we spend increasing amounts of time in doctors’ waiting rooms.

If we make it that far. I’m in my early ‘60s, and it’s kind of amazing how many old acquaintances didn’t make it this far. I could die tomorrow, or Rhumba could. That’s true every day of your life. Deferred gratification: is it prudence? Or a trap?

Some people “make it that far” by 60 or less. Sometimes much less. They’re lucky, or good with money, or both; I don’t hold it against them. I’m watching them in the deli, hanging out in the sunshine and nibbling on muffuletta while our fellow citizens sit in cubicles or stand behind counters robotically saying “Have a nice day” to people who, in the majority, are not having one.

If a young person today were to ask me, how to plan for the future, I would say: don’t wait for the golden years. All years are golden. Follow your dreams now. Take risks; learn; fail. Be golden. Stay out of debt — if you can.

Because you could spend your whole life in harness and not make it far enough to reach that distant, shimmering golden vision. Or find that your hard-earned pensions and funds vanish in a financial crisis or predatory fund management. I no longer have faith that the present is the future.

I have a pension. I have funds. I have Social Security. Will I have them in five years? Anymore, in a system so rotten as ours, I cannot rest easy in that regard. And so I can’t tell a young person to follow my path, because it might lead off a cliff. And I am absolutely sure that, for better or for worse, their options in older age will be completely different than ours. This system won’t last that long.

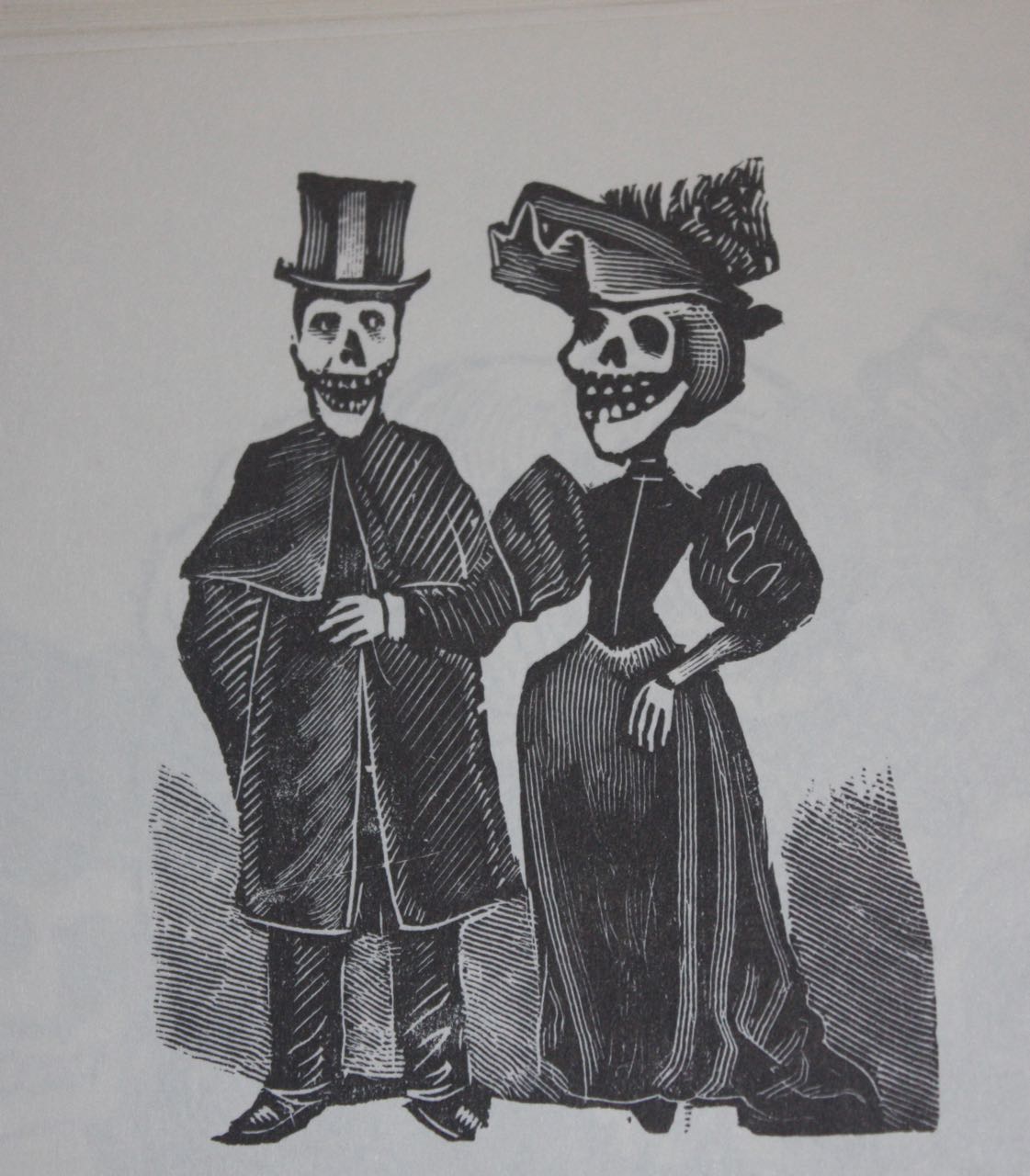

But in the meantime, Rhumba’s ready to launch, is in fact having her retirement party this week. And I’m going to do my bit to make her time post-workplace as long and golden as possible. And join her there as soon as I can. Maybe there’s a way to accelerate my schedule.

Because the only possible answer to the people who ask, “What are you going to do with all your time” is… “everything.”