I can kick my own ass. It’s a skill. I discovered it in old age after losing a lot of weight.

I simply kick backward with either leg so that the foot rises up heel-first and smacks a buttock. It’s not a traditional kick, but it’s a kick. (Thud!)

This ability has proven useful: I want to kick myself in the ass every time I see this shirt. For a research satellite. (Thud!)

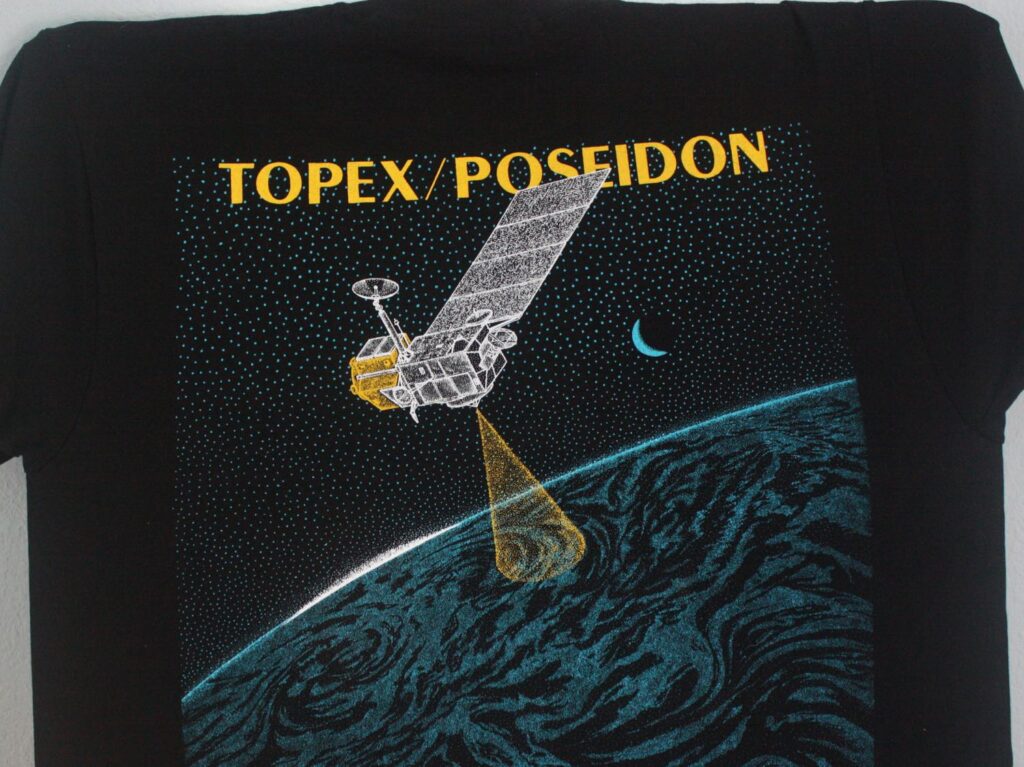

Launched in 1992, TOPEX/Poseidon was a joint U.S. / French probe that mapped the topography (the surface) of the sea: the high spots, the low spots, the ripples, the bugles, the currents, the heat sinks.

They called the probe an ocean altimeter. TOPEX/Poseidon was the first solely oceanographic research satellite, and it sensed and described patterns of ocean circulation and how they affected climate. It looked for patterns inside El Ninos and La Ninas, studied coral reef health, and more. Such hard information was never available before; theories, sure, but no proof. TOPEX/Poseidon was a big deal.

It still is. Scientists would know a lot less about climate change without TOPEX/Poseidon. As for the name, it stands for “Topography Experiment Poseidon:” Poseidon, Greek god of all the oceans.

The mission team kept TOPEX Poseidon flying for 13 years; it was only meant to last for three to five. But when the five years were up and TOPEX kept phoning home, they found new things for it to do, and do, and do.

And at every mission milestone, there was another t-shirt: from launch to new missions to decommission. I found five of these tees at Goodwill one afternoon.

Some engineer or bureaucrat had stayed with the program from beginning to bitter end; and they’d saved each t-shirt and never wore any of them. The history of a space mission — in t-shirts. It’s something rare and, in retrospect, precious. At least to me, now.

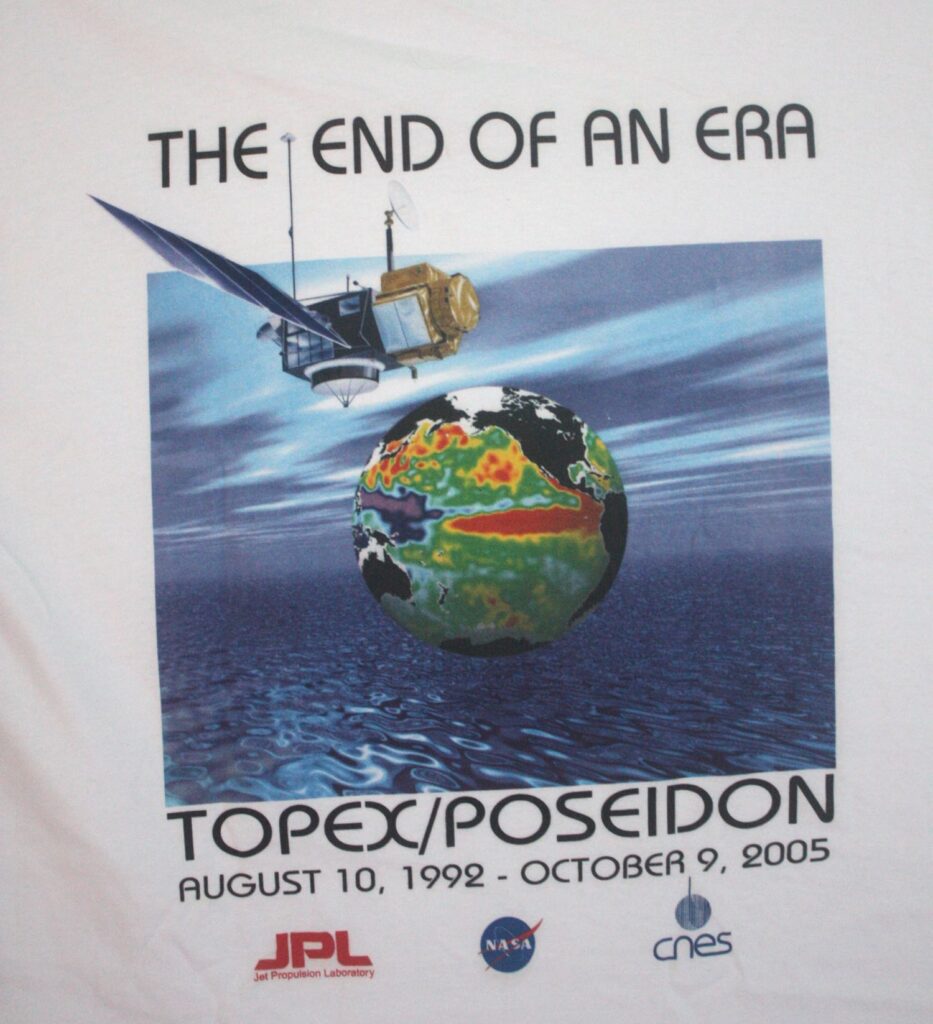

And I only took the first one and the last one: “I don’t have the space for them all,” I told myself. (Thud!) Here’s the last one. It’s a beauty: TOPEX Poseidon, soaring over a colored heat map of the world’s oceans.

TOPEX Poseidon’s attitude control — its ability to rotate itself — failed in 2005. The mission team turned off the lights, made this final t-shirt, and went on to other things. But not before the probe had worked in tandem with its successor satellite, JASON-1, for several years of valuable research. Among other things, “JASON” stands for the Jason of Greek mythology, an explorer of mysteries and oceans.

“The End of an Era,” the final t-shirt proclaims. But the larger mission continues: after JASON-1 came JASON-2, and then JASON-3. Before each Jason went dark, the next one took its place. The research goes on.

I recall a line of poetry that describes machines as “the children of our brains.” This idea sticks to me: that a machine is the sum total of the ideas and dreams of its makers, transformed into reality by the ingenuity and craft and dedication that they bring to bear.

Few machines deserve more praise than those exceptional space probes designed and built with such care and skill that they transcend their mission parameters and achieve unexpected greatness. They do this only thanks to engineers and scientists and program managers and flight controllers like those who made TOPEX Poseidon fly, and thus transformed our knowledge of ocean health and climate change.

Such probes are the children of dreamers: dreamers who built a dream out of hardware and software and launched it into the cosmos.

And who also went home from work from time to time with yet another mission t-shirt on the back seat of the car. Five in all — at least.

Of which I took just two. (Thud!)