Ask “Who invented the Hawaiian shirt;” then find a large sack to hold all the answers. These answers lie scattered across half a millennium and half the earth. They’re all different. And they’re all true.

But first: what is a Hawaiian shirt? Really?

A Hawaiian shirt is a loose-fitting resort shirt made of lightweight fabric — usually cotton, but often rayon and even silk — with a colorful and pictoral pattern. It is designed for tropical weather: cut boxy, not form-fitting, to allow for airflow between the skin and the shirt on sticky days. Most Hawaiian shirts have a loose or flat collar, worn open, so that a sweaty neck can catch the breeze.

A Hawaiian shirt is also cut long; it falls across the thighs. This shirt is meant to be worn “tails out” for ease of movement and additional air circulation. Vents on each side allow even more airflow. Hawaiian can be short-sleeved, long-sleeved, even pullover. These days you see mainly the short sleeved, buttoned variety.

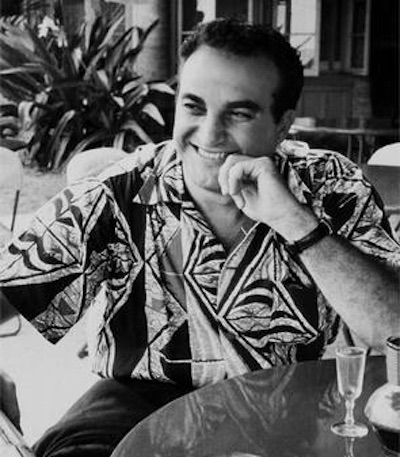

Hawaiian shirts appeared in 1930s Hawaii for the new tourist trade. In Hawaii they were (and are) called aloha shirts. In Hawaii, “aloha” (peace and love, more or less) is a common salutation. And also a catchword in 20s-era marketing campaigns aimed at welcoming tourists to the islands. Back then, mainly the wealthy could afford to travel to Hawaii. Damned right they were welcome.

Aloha shirts were revolutionary, at least in the U.S. Warm-weather or resort clothing had always been as structured and fitted as traditional clothing; resort clothing was simply made from lighter material, usually white or light-colored. The loose, casual aloha shirt helped to change that.

It also changed what could be on a shirt: not just stripes and checks and colors and regular patterns, but larger and more pictorial graphics: palm trees and tropical scenes and Diamond Head and surfers and exotic flowers and beautiful girls in grass skirts. Aloha shirts were about tropical beauty, tropical ease, peace and love: aloha.

At first Hawaiian shirts were largely made, marketed and sold in Hawaii — and yes, called aloha shirts. Later they were also made and marketed in the states as beach wear and resort wear. In the states they were tagged with the more generic name “Hawaiian shirt.”

These days in America you can wear a Hawaiian shirt anyplace where the weather cooperates: at the mall, at the big box store, on a date, in a fine restaurant, in church. Wherever. I haven’t seen one at a funeral — yet. Here are some modern shirts that fit both into the aloha shirt and Hawaiian shirt genre: even the one with the vintage fighter planes and hibiscus flowers (Hawaii’s state flower).

Aloha/Hawaiian shirts are still designed and made in Hawaii, but they don’t have to be. Outside of Hawaii, the “Hawaiian shirt” — minus aloha — is now a worldwide genre of shirts: any resort shirt with vivid graphic elements. “Hawaiian shirts” are designed and made all over the world.

On today’s generic Hawaiian shirt, tropical or floral scenes are still common; but so are cars, airplanes, liquor, dragons, guitars, dice, cacti, skulls, what have you. Some manufacturers use the name “cabana shirt” or “resort shirt” or “camp shirt” for generic Hawaiian shirts. But to the great American public, it’s all “Hawaiian shirts”.

Here are some shirts that are strictly “Hawaiian shirts.” Nothing “aloha” about them, even if they were made in Hawaii (I doubt that any were). But every one of them was marketed as a “Hawaiian shirt.”

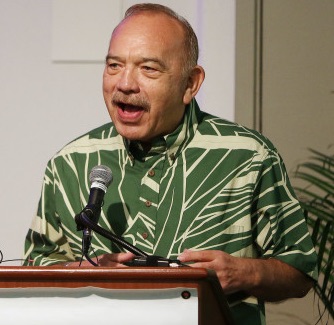

Out in Hawaii, the locals don’t care who wears an “aloha shirt.” Cultural appropriation is off the table, because “aloha shirts” began as a tourist gimmick and still are. You can buy plenty of trashy aloha shirts in Honolulu. But Hawaiians do buy and wear aloha shirts that fit their own tastes. What Hawaiians really call aloha shirts are “shirts.”

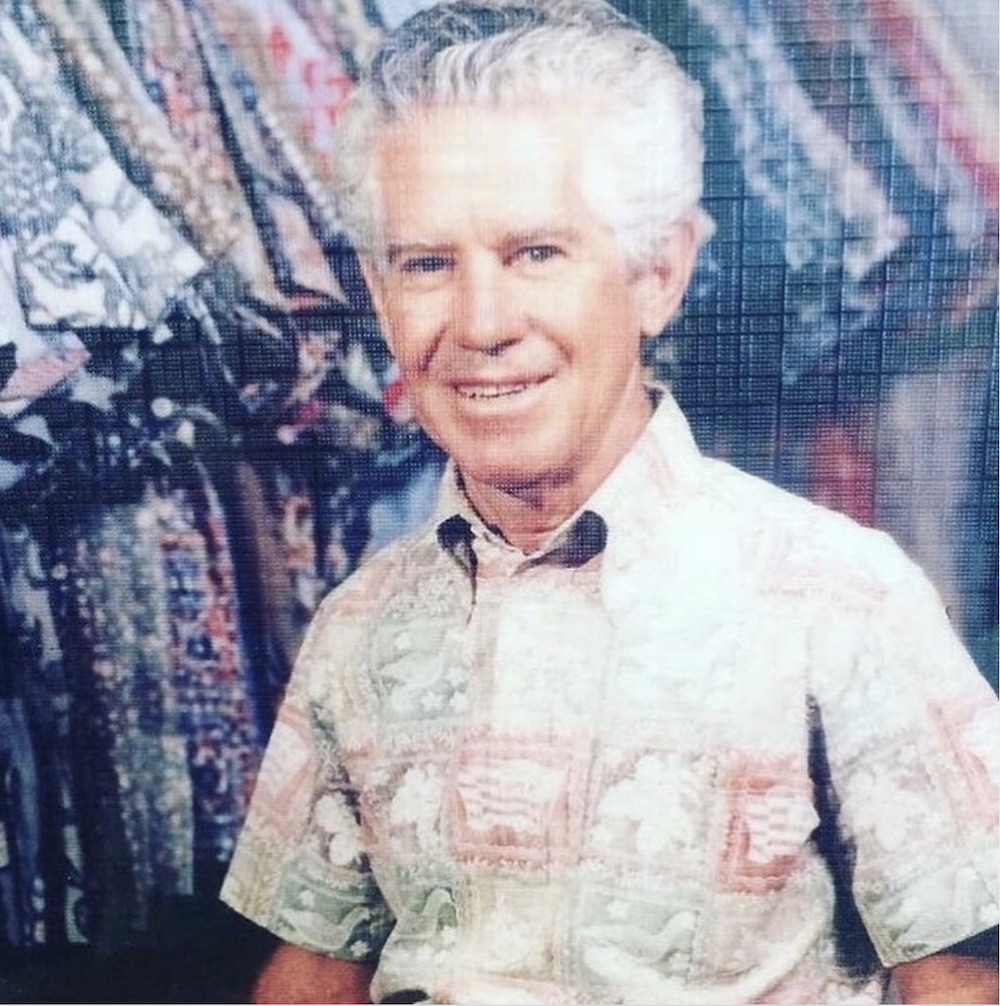

Locals treat aloha shirts as formal garments for business, politics, and important social functions. (Many West Coast businessmen feel the same way, at least some of the time.) The aloha shirts that that they prefer are still made or at least designed in Hawaii.

A typical aloha shirt made for real Hawaiian sensibilities) comes in more subdued colors than their mainland counterparts; its design invokes Island culture and history and flora, or even the culture of other Pacific nations. No hula girls, no liquor bottles, no cars or dragons, no space ships.

Hawaiians also enjoy aloha shirts that are long-sleeved or pullovers. Aloha shirts like these have always been made. But on generic Hawaiian shirts, they’re rare.

So these are all the things that an aloha shirt, or a Hawaiian shirt, can be. But… no, not really. The Hawaiian shirt is just one member of a grand family of tropic shirts that spread across the world over the centuries. Spread by whom, you ask?

Try the Empire of Spain, staggering across the globe like a drunken conquistador for over 300 years. Stepping on cities and nations. Looting a hemisphere of its gold and silver so that newcomer Spain could strut around Europe like the big boys. Joined at the hip with the Roman Catholics, and thus doing its clumsy best to bend the peoples of a hundred ancient cultures into useful Spanish-speaking Catholics in the name of Mother Church.

And, along the way, spreading a grand tradition in tropical men’s shirts all across the world.

Anyway: when you’re on a world conquest God-is-on-our-side kind of jag, nothing’s ever enough. So after the Empire trampled the New World, it leapt across the Pacific from the Viceroyalty of New Spain — Mexico, the Caribbean, and environs — to occupy the Philippine Islands and, from there, continue the economic and cultural domination of Asia!

That last bit… didn’t work out. But the Empire kept the Philippines anyway and converted them to Catholicism — more or less. Tribes that had already gone Muslim didn’t want any Spaniards telling them what to believe. There was always trouble somewhere.

But the Filipinos made valuable subjects. They had useful skills and knowledge. They’d traded with the outside world for centuries, worked metal, made things — and wove cloth and embroidered cloth for clothing.

Thus, decent clothing was there for some. And thanks to the tropic heat, Filipinos thought hard about clothing that could keep you cool. Some of it looked pretty good, too, especially if you were high caste.

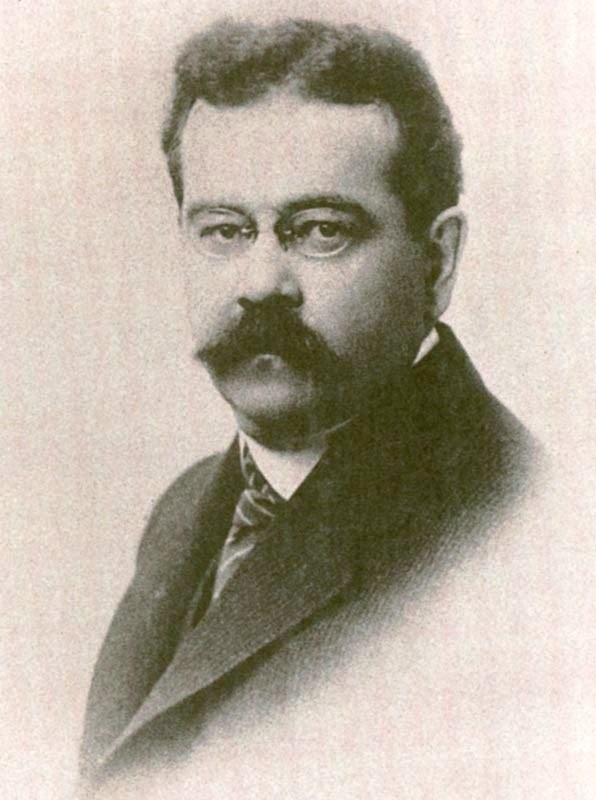

Over the centuries before and during the Empire, Filipinos thus evolved their own true shirt. It was (and is) a loose job called the barong tagalog, bearing local and Western and Chinese influences.

The fancy, traditional version was made of woven, translucent pineapple fiber covered with embroidery. It was so translucent that it required a long-sleeved collarless undershirt, which the Filipinos adapted from Chinese work clothing. (The chemise de chine, which is worn to this day by itself as informal wear; kind of the equivalent of wearing a t-shirt.) The formal barong looked like this:

You can still get that kind of barong. But then and now, it’s formal wear for special occasions. A sort of “everyday” barang grew up at the same time: a respectable garment for work and for any kind of business.

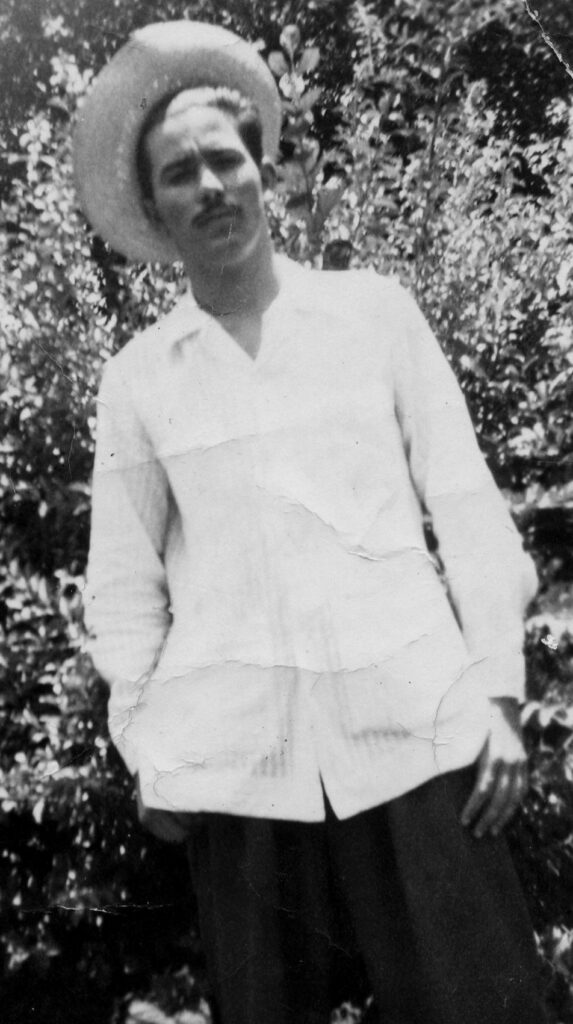

This everyday barong was made from common, opaque cloth. A French painter wandering the Phiilipines made this painting of a barong-wearing Filipino fisherman in 1848.

Looks up-to-date, doesn’t he? Beach-ready, even. The patches on the shirt show his poverty, however. Spanish rule wasn’t so wonderful for the people at the bottom.

Nevertheless: it’s a Hawaiian shirt, minus the tropical flowers and hula girls. It may seem everyday to you, now; but back then there was nothing else quite like it in the world.

As you’ve seen, old-school made-in-Hawaii aloha shirts commonly came with long sleeves and as pullovers. Apparently that was true even in the Philipines. Open collar, boxy shape, cut long across the thighs and worn tails-out. There even would have been vents, though you can’t see them here. Button-up fronts and short sleeves were around at some point, if you wanted them.

Look below to see what barongs look like today. The traditional translucent barongs are still out there for special occasions — sometimes with some pretty spiffy embroidery.

More casual versions are made of regular cloth, and there are every “everyday” or “office” barongs that look a whole lot like the average Hawaiian shirt. Substitute embroidery for patterned cloth, and you’re there.

If the painting of the fisherman dates from 1848, it’s no stretch that this basic design extended back into the 1700s — and who knows how far beyond? And that’s important: because the Spanish Empire took the barong to the New World — New Spain — before the shirt ever got near Hawaii. The barongs came over on the backs of Filipino sailors on massive sailing ships called the Manila galleons.

You thought we were ready to go to Hawaii, right? Wrong. The barong has more work to do first.

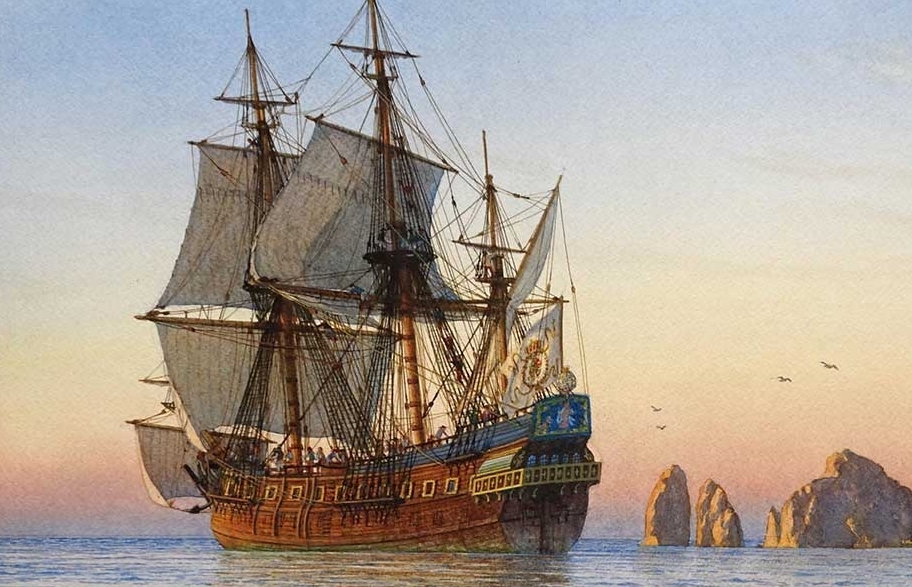

As for those Manila galleons: the Spanish Crown kept a monopoly on trade with the Phillipines from the mid-1500s till nearly the end of “New Spain” 250 years later when Latin America broke away from the Empire. Once or twice a year, a giant galleon full of silver mined in the Americas would set off from Acapulco to Manila in the Philippines: an arduous journey of several months.

In Manila, Chinese merchants would await with the treasures of the Orient — porcelain, artwork, silks, jade, spices, special and rare objects of all kinds. With the transactions completed, the Manila Galleons brought the treasure back to Acapulco on an even more arduous journy. From there the goodies would pass on into the Empire. No foreign ships were allowed to trade.

The Manila galleons were the fabled treasure galleons of old, carrying so much more than mere silver. Filipinos crewed them (and built them), along with Spaniards and Mexicans and Chinese. The Filipinos wore their barong tagalogs all the way to Mexico and back.

Some of those Filipino sailors stayed in Mexico. A new start in a new land always has appeal, especially if you speak the language. The Spanish colonial government and priests spoke not only Spanish, but Mexican Spanish.

Today, several million Mexican citizens claim Filipino ancestry from those days and after. (More Filipinos would immigrate later.) The sailors got to know Mexico, and Mexico got to know their barongs. Where the weather’s hot, the barong can’t be beat.

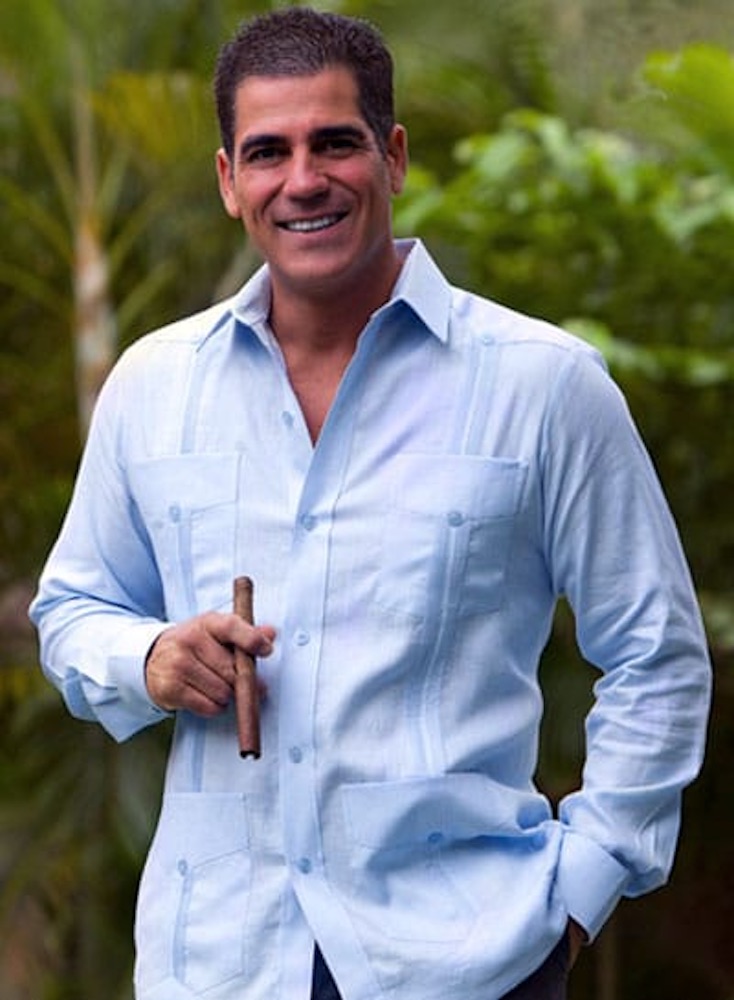

Eventually the barong became the guayabera, a respectable garment for work and business and even church in Mexico. This was particularly true on Mexico’s east coast and in the Yucatan, where the weather was hot and muggy.

Cuba has claimed the guayabera as its own invention, but the historians lately say otherwise. Especially since a type of guayabera found in the Yucatan is sometimes called the “Chemise de Filipina” (Filipino shirt).

The Cuban guayabera has its own special features, though, and we should mention them. We Americans consider the Cuban version to be the true guayabera: they were the guayaberas that rich American tourists brought back to America from the Caribbean in the 20s. Americans fell in love with the light and cool guayaberas that the Cubans wore.

And now, those special features: two vertical rows of closely sewn pleats run up the front and back of the shirt. In the back the pleats run up to the ribs of a yoke and then stop. Buttons are placed at the tops and bottoms of the columns of pleats, and also on the pockets.

Traditionally the guayabera comes in white or pastel colors, but modern guayaberas can come in any color. Collars can vary — a flat, open collar called the “camp collar” or Cuban collar is a traditional favorite. But less-flat yet still very open collars have also grown popular.

Different regions have different flair: Mexican guayaberas, for example, often have fewer (or no) pockets and can feature embroidery. The fancier Mexican guayabera is sometimes known as the “Mexican wedding shirt.”

What with the embroidery and style, Mexican guayaberas can look a lot like barong tagalogs back in the Philippines, minus the translucent cloth. Is that at all suprising? Some of them may even sport a Chinese-style band collar like Filipino barongs of old.

So, are we ready to go to Hawaii now?

Not quite. The Mexican guayabera had a child — which means that the barang tagalog had a grandchild. It looks something like this:

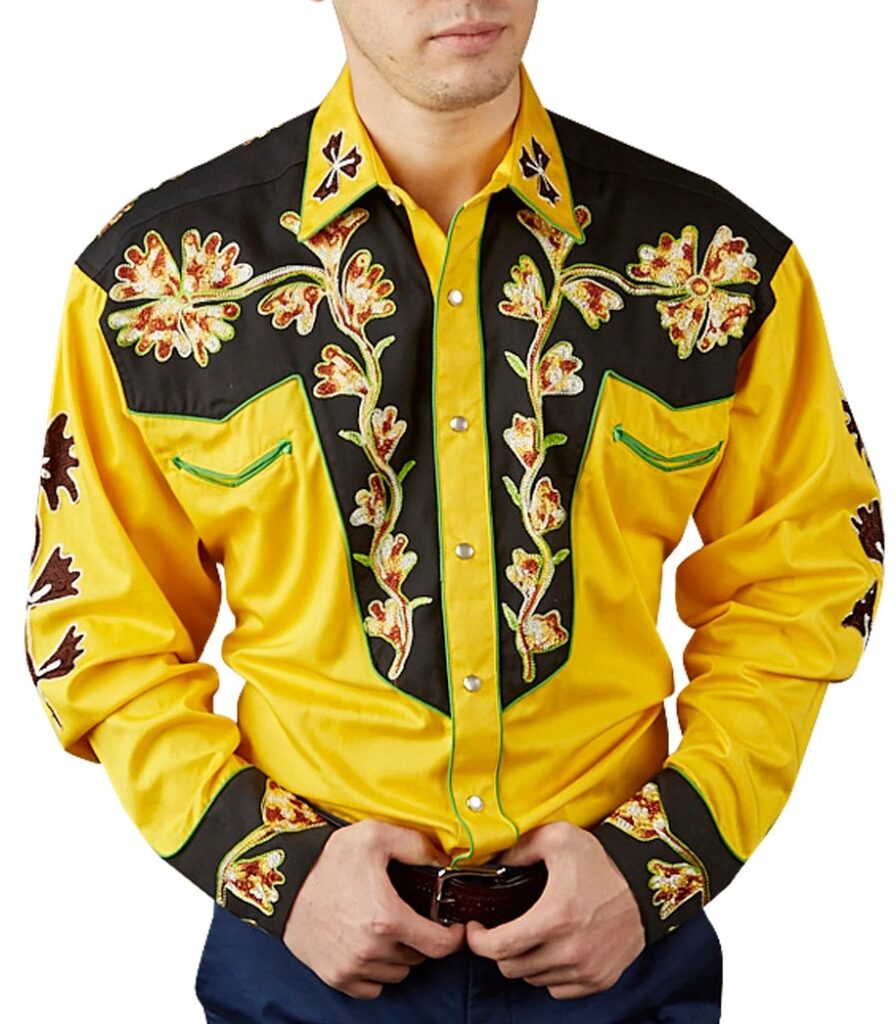

The time is the late 1800s. The place is the American West. The major industry is cows. They’re everywhere, and so are cowboys: grazing cows, herding cows, branding cows. Cowboying is a tough job, and it needed a tough shirt. But there wasn’t cloth to sew them with on the frontier; cowboys wore hide shirts, tribal clothing, or whatever they could find.

That changed when the railroads came through; at last yardage could be ordered from the big eastern mills. Before long prairie tailors began casting around for a good cowboy work shirt design. What they saw were guyaberas on the back of Mexican caballeros who’d ridden north for work. They saw big yokes with pointy ribs that reinforced the shirt. They saw embroidery, because why not? And they saw long tails that could tuck deep into pants and not slip out during a long horseback ride.

And that all made sense. And so the cowboy shirt was born; they even kept the many buttons, but turned them into metal snaps that securely fastened pockets and sleeves. A victory for the guayabera: and the barong tagalog.

So are we finally going to Hawaii?

Okay, yes. At last. But the barong does not make its way to Hawaii from the Americas all by itself. Once again, the honor belongs to: The Empire of Spain!

It fell.

In 1898. With a resounding thump. And soon after it fell, Filipinos could freely come to Hawaii — with barongs on their backs.

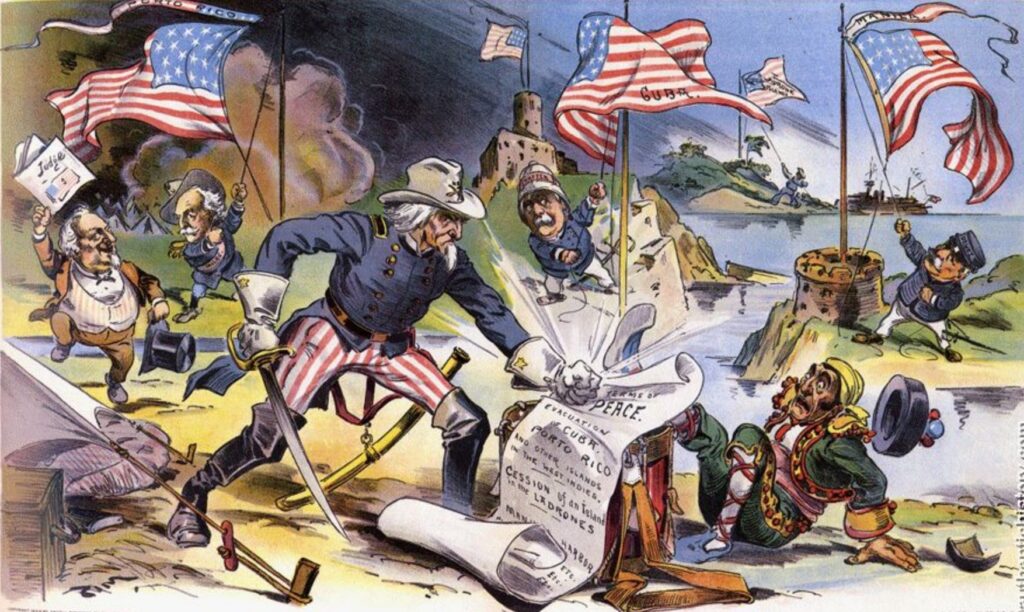

Spain had long ago lost most of “New Spain” and its South American viceroyalties. In 1898, it also lost the Spanish American War. Spain had to cede most of what was left to the United States. That included the Philippines. So a Spanish possession became an American overseas territory.

Hawaii had also become an American territory, thanks to a coup by American plantation owners that took down the Hawaiian monarchy. That meant that Filipinos were not exactly “foreign” anymore, and could come to Hawaii easily.

The same plantation owners who’d overthrown the monarchy were thus eager to bring in impoverished Filipinos on contract to work sugar cane fields at cheapest possible wages. The idea was to put pressure on Japanese field workers who wanted more money.

As not-quite-foreigners, Filipinos could also stay in Hawaii after their work contract was over. Many did stay, because they could bring over their families to live with them in conditions that were better than home.

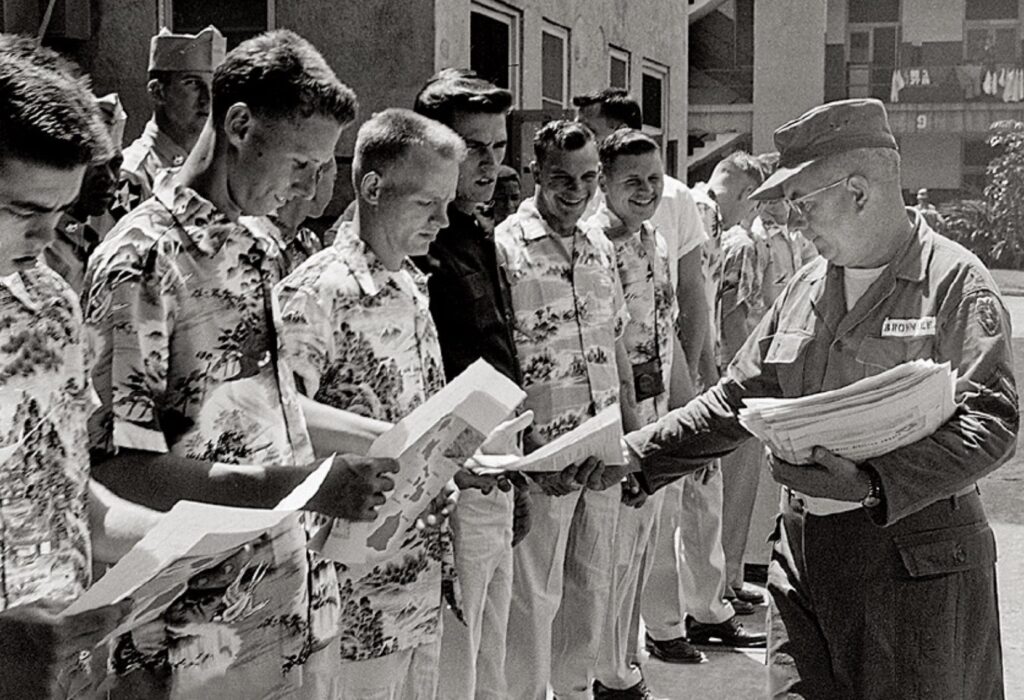

Soon Hawaii had a permanent barong-wearing Filipino community. What worked in the tropic Philipines worked equally well in tropic Hawaii. This was all in place by 1920 or so. By that time Filipino plantation workers had allied themselves with the Japanese to strike for better wages.

Charles Fort, the pioneer researcher of strange phenomena, once declared that sometimes “it’s steam engine time.” In the 1700s, all the circumstances and forces needed to develop a steam engine seemed to magically come together in several places at once. This pattern repeats throughout history. Thus in the 1920s, Hawaii entered “aloha shirt time.” The aloha shirt wanted to happen. It was going to happen.

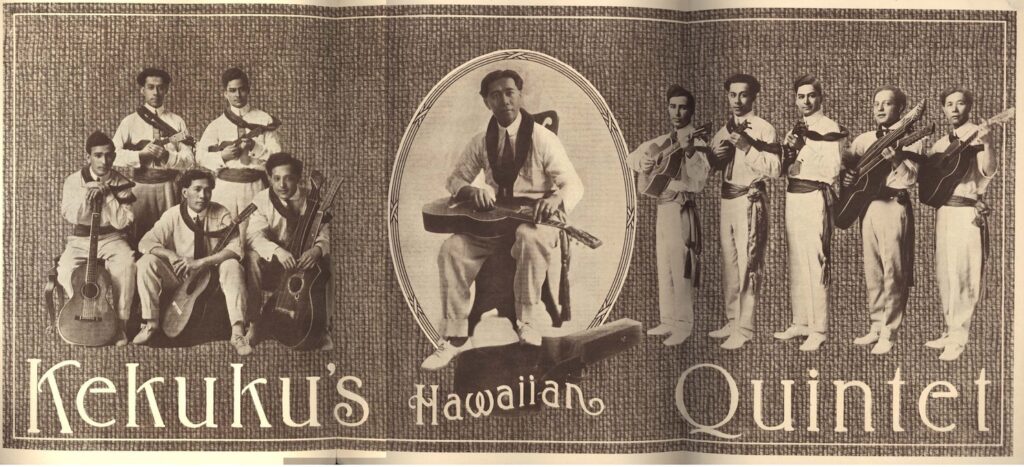

As usual, money was key. Hawaii had marketed its allure to the mainland for years. Hawaiian music and lore was huge in mainland culture: the islands were celebrated as America’s new, bona-fide tropical paradise: mainly for the wealthy who could go there by passenger ship. But everybody could dream.

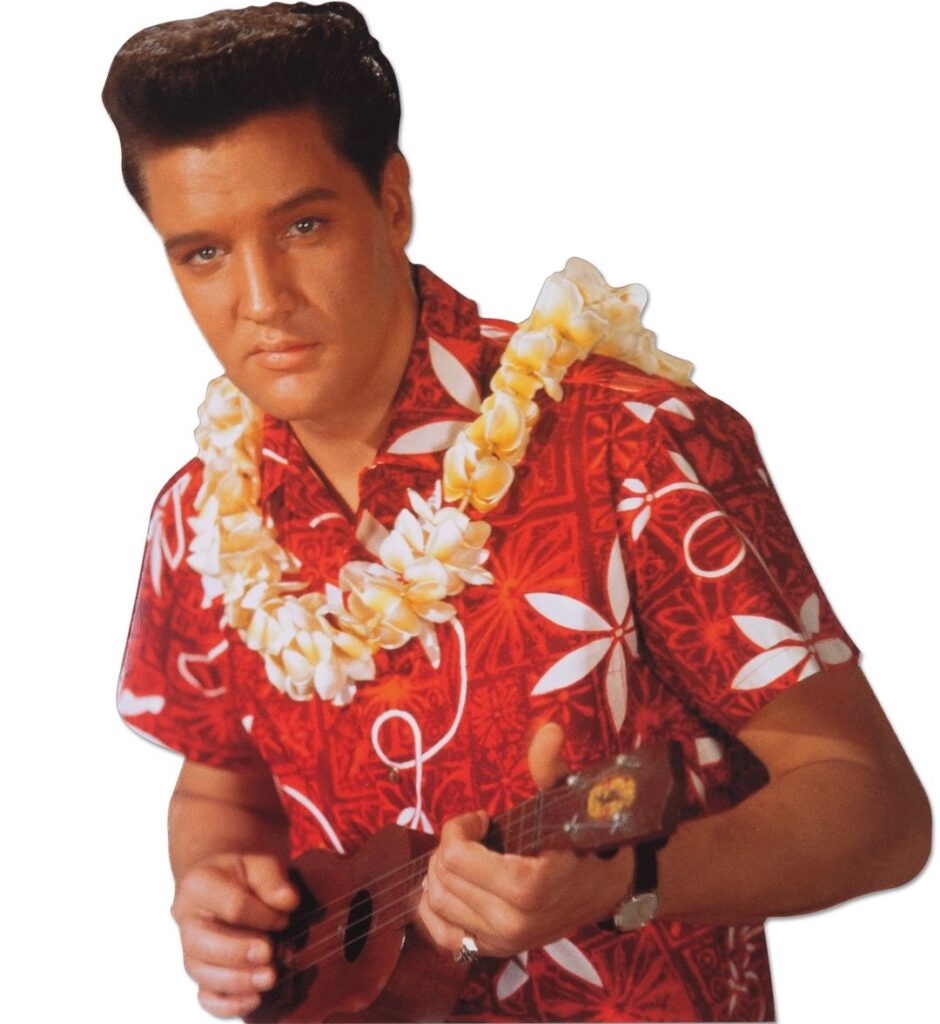

There were publicity campaigns, radio shows, records. In the U.S there were hardly any record charts in 1916, but Hawaiian music topped them. Hawaiian steel guitar music took America by storm. Even ukelele sales boomed. In Hawaii, “Aloha” became a tourist catchphrase: there were aloha hats, aloha trinkets, aloha anything.

There would be aloha shirts. Hawaii knew about shirts: The old Hawaiians had worn clothing made of pounded tree bark block-printed with vegetable dyes, as they had no fibrous plants to spin. Pounding tree bark wasn’t a lot of fun; there wasn’t much of a color palette, either. So Hawaiians eagerly adopted western-style clothing when the Americans showed up.

But everyday “ready to wear” shirts weren’t that common, except for work clothing. If you wanted a nicer shirt, you would probably pay someone to make it for you — or make it yourself.

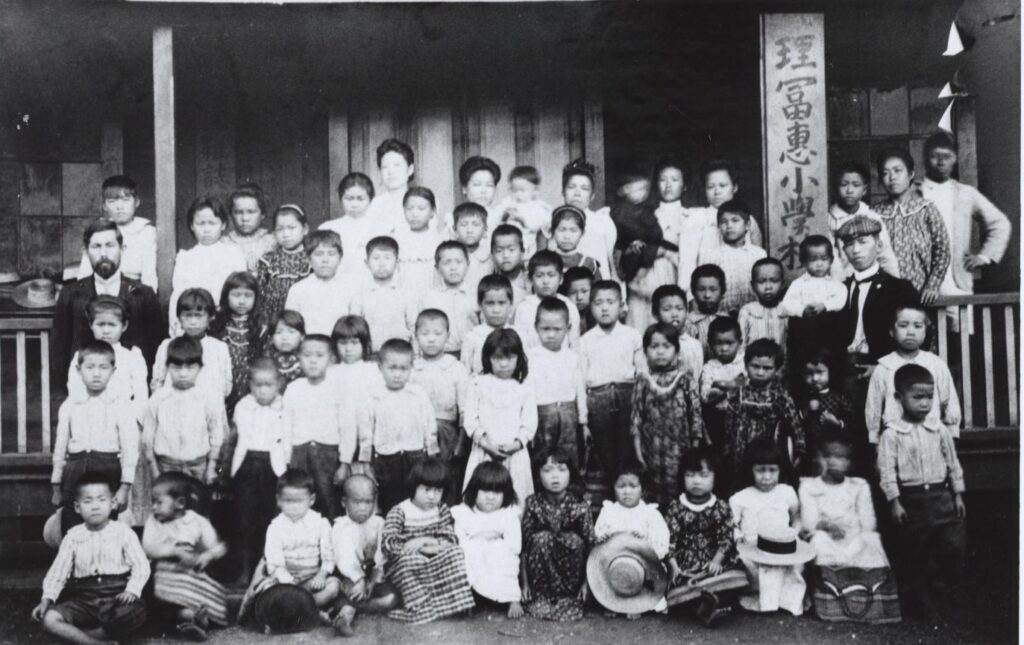

And it just so happened that a lot of people could make shirts. Many Chinese immigrants went quickly into the clothing or dry goods business. The Japanese immigrants knew, too: every woman, and some men.

Moreover, every daughter of Japanese immigrants — the Nisei generaiton — learned to sew in the Japanese language and culture schools that Japanese children attended after public school finished for the day. Sewing was in the girl’s curriculum just as it would have been back in Japan. Apparently some were even taught on machines.

So a lot of locals made shirts to order, or for themelves. Chinese and Japanese tailors in Honolulu and elsewhere would certainly do it for you. Japanese field workers might make shirts as a sideline. There was even a custom for Japanese men to make at least one shirt for themselves.

The Japanese home sewers and tailors liked to make shirts out of colorful cotton yukata fabric from Japan: geometric patterns, bamboo patterns, things like that. Professional tailors might use something similar, or more expensive Japanese silk kimono fabric with much more elaborate images. .

And so the shirt just sort of began to happen. The barangs were around. Teenage raised-in-Hawaii Filipinos began wearing barang-influenced shirts called bayau (“friend”) shirts: tails out with colorful fabric and the basic barong design.

A rich white kid at the University of Hawaii had (well, his mother had) colorful shirts made for his classmates. White kids at the private high schools started having colorful shirts made. And as somebody said wryly, when the white kids started doing it, everybody noticed.

The Waikiki Beach Boys — the “watermen” at Waikiki who taught wealthy tourists how to dive and surf and paddle — also began wearing colorful shirts.

Well-off tourists saw those shirts: they were another world from the formal resort wear of the time. Some asked a beach boy about it and were directed downtown to have the tailors make shirts for them, too, out of the fine kimono fabric.

There was not yet any cloth with Hawaiian-themed designs, but cotton yukata and silk kimono cloth did the job — even though you got pines and Mount Fuji instead of palm trees and Diamond Head. One could also find fabric from Polynesia with designs resembling traditional Hawaiian block-printing.

Real Hawaiian-themed fabrics would show up before too long. Artists and fabric designers already lived in the islands: some from the mainland, some local. Some locals would simply learn.

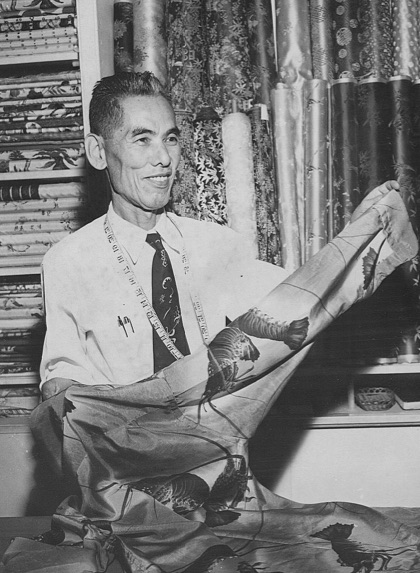

At some point one of the downtown cloth merchants — maybe a Japanese tailor, maybe a Chinese dry goods merchant, opinions vary — decided to get ahead of the game and run up a batch of the shirts on spec. He put them in the window as ready-to-wear merchandise with a display sign reading “aloha shirts” or “Hawaiian shirts” (depending on who you believe) And the rest is history.

Although nobody agrees on who first coined the term “aloha shirt,” either.

In the end the Honolulu shirt-makers gave the world the Filipino model, a barong: usually short-sleeved (though not always) with buttons (though sometimes a pullover) and otherwise a flat-bottomed barang except for the flashy fabric. A boxy, colorful, breezy, open-collared shirt for tropical tourism? Why not? It worked.

And it was meant to be worn tails out, as a barong always was. That was a big, big deal. Americans tucked in their shirts, always had. Tails were worn “in.” Shirts designed to be worn tails out were radical — and just right for tropic weather.

By the late ’30s, tails-out guayaberas from Cuba were also making inroads in the US-mainland resort wear market. They mutated into the “camp shirt:” a simplified guayabera without all the pockets, buttons, and pleats, but usually with the flat, notched camp collar or “Cuban collar.” Camp shirts became the popular warm weather recreation and resort shirt in the American East. The children of the barong tagalog streamed into America from Cuba and Hawaii simultaneously.

So aloha shirts caught on — though known as Hawaiian shirts to the rest of the world. Demand grew; small shirt-makers sprung up everywhere in Hawaii. Staid tailors and dry goods dealers, and a few adventurous mainland entrepreneurs, found themselves building resort-wear businesses: dozens of them. Most of them were small time; they came and they went. But not all went.

Even World War II couldn’t kill the shirts. Tourism was dead for the duration, but the locals began to wear them — they liked them and couldn’t get mainland clothing easily. You could go down to the military bases and shipyards and see Hawaiians do war work in aloha shirts

Moreover, the soldiers and sailors who passed through Hawaii all wanted aloha shirts. They’re read about them: Hawaii had been an American fascination their whole lives. And those that lived to go home, took their shirts back home with them.

And all those shirts on all those servicemen were churned by all those young Japanese-American Nisei women who knew how to sew and were happy to have sit-down work at a sewing machine instead of hacking cane under the hot sun.

By the way: only a very few Hawaiian Japanese went to internment camps during the war. They made up close to 40 percent of the population; the Hawaiian economy would have collapsed. And the military needed that economy at America’s forward base in the Pacific theater of war. The military put a stop to deportations pretty quickly. Aside from that, most of the population did not see “their” Japanese as the enemy.

When tourists returned after the war, things really took off for the aloha shirt and Hawaiian-made garments in general. Resort clothing became Hawaii’s number three industry. More mainlanders came out and founded new clothing businesses, lured by the Hawaiian lifestyle. And any good seamstress could get a job at the drop of a lei.

And then California resortwear companies started making them, and then larger shirt companies all across the country, companies with names you’d recognize. And in the end anyone anywhere could make a Hawaiian shirt. Or a barang tagalog, or a guayabera, or a cowboy shirt. And they do.

It should be noted: a lot of the post-war shirts made in the islands had camp collars: the flat collar that had originated with Cuban guayaberas, moved north on American camp shirts and in the end made its way onto true Hawaiian aloha shirts as one of several collar styles used.

And this is still true. In fact if you were to head to the Philippines and go barang shopping, you just might find camp collars on some of the “modern barangs.” (See the images earlier in this piece.) Cutural history is the snake that eats its own tail. It winds round and round; the beginning is the end, the end is the beginning.

Everything mutates. There are Hawaiian or aloha shirts with traditional stiff collars and even trim ivy-league tailoring. There are short- and long-sleeve barangs with both stiff and flat collars and with or without elaborate embroidery; and the same can be said for guayaberas.

Some wear them for play, some for doing business. But they always wear them when the weather’s warm and humid. And if they do, I guess they can thank a Filipino. And perhaps the Spanish Empire.

Oh. We’re not done.

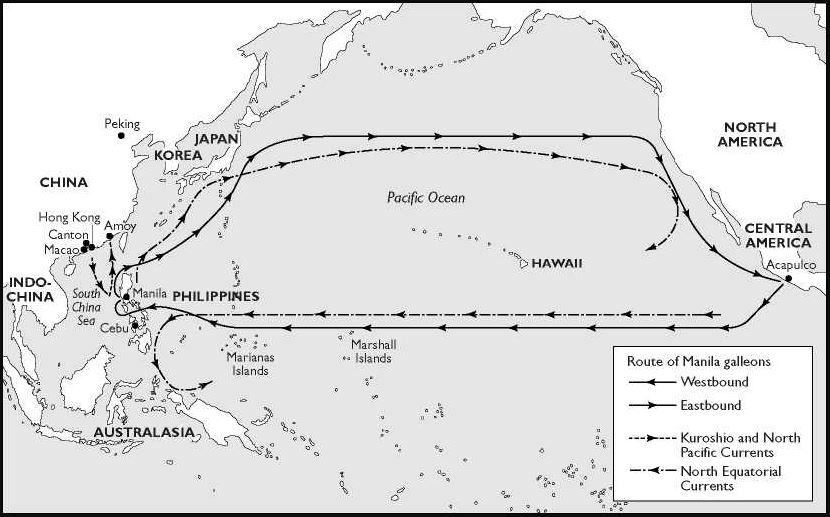

The question I never answered, the question maybe you never asked, is: why did the Spanish Empire never make it to Hawaii? They owned the Philipines and several other Pacific island chains. Empire ships criss-crossed the Eastern and Central Pacific for 200 years before Captain Cook even showed up. They should have got to Hawaii and claimed it. But they didn’t.

The chart above shows the routes that the Manila Galleons — and all other Spanish ships — followed to cross the Pacific. They miss Hawaii completely.

The winds and currents on the southerly route carried the big, clumsy galleons west from Mexico and finally to the Philippines. Favorable easterlies on the eastbound route carried them north and east from the Philipines and eventually to the California coast. From California the galleons would follow the the coast south to Acapulco. This took another month.

The Spanish spent 30 years searching for those currents and winds; only with their help was the trip possible. Their galleons couldn’t tack well against the wind. Even with good winds, the trip took months each way.

There are stories that one Spanish expedition made it to Hawaii early on,while searching in vain for a good west-to-east route. But as the story goes, they found nothing worth going back for. The Empire of Spain did not surf.

The northern route from Manila back to Acapulco was the longer and the harder. Disease, exposure, scurvy, bad food, hunger: they took their toll. Dozens died on each trip. By the time the galleons reached the California coast, most crews were in heartily bad shape. And there was still no rest or resupply until Acapulco, a month south.

That changed in the late 1700s, when Spain actively set out to colonize California. A capital and port, Monterey, was established on the Monterey Bay about 90 miles south of where San Francisco lies now. The Manila galleons were commanded to stop there on the way to Acapulco: to pick up communications, and probably to lick their wounds. Many captains were in too much of a hurry to stop but some — their crews or ships in need of repair — did pull in.

The Monterey Bay is semi-circular: a big bite out of the mega-slice of pizza that is the north-south-oriented California coast. I live on the north shore, in Santa Cruz. A short walk from my house brings me to a view of the city of Monterey, 20 miles across the bay on the south shore.

I am of course very interested in Hawaiian shirts. In Santa Cruz, Hawaiian shirts are almost formal wear, as is so in Hawaii and back in the Philipines themselves.

Thus it’s one of those random jokes of history that, if I were to travel back in time 250 years or so, I could watch a Manila galleon drift by like a great white-winged bird on its way to Monterey with a complement of Filiipino seamen — not so many as left Manila — wearing 18th century barong tagalogs.

They were just passing through, those barongs of old. But they would be back, as Hawaiian shirts, I can go downtown and buy all I want .

Remember what I said about cultural history? It’s the snake that wraps around itself and eats its own tail. Here in Santa Cruz as much as anywhere. Or everywhere.

The Spanish Empire is gone, but the barong and its descendents survive everywhere that the Empire used to rule: up into the American Old West, down South America to the tip of Chile, in what was once New Spain and, these days, even in old Spain itself.

And in Hawaii, thanks to migrating Filipinos looking for a new start in life. Aloha.