Wars of aggression are all similar: somebody less powerful than you has something that you want. So you mass your armies, roll over them, and take it. There may be excuses. They are just excuses.

War can be that simple. Unless you’re NOT more powerful after all, and the party you’re attacking has powerful friends. Does the war between Russia and Ukraine come to mind? It should.

But war needn’t be about land and resources or twisted dreams of manifest destiny. It needn’t even involve nations and armies. It can be about real estate development and gentrification. And taco trucks.

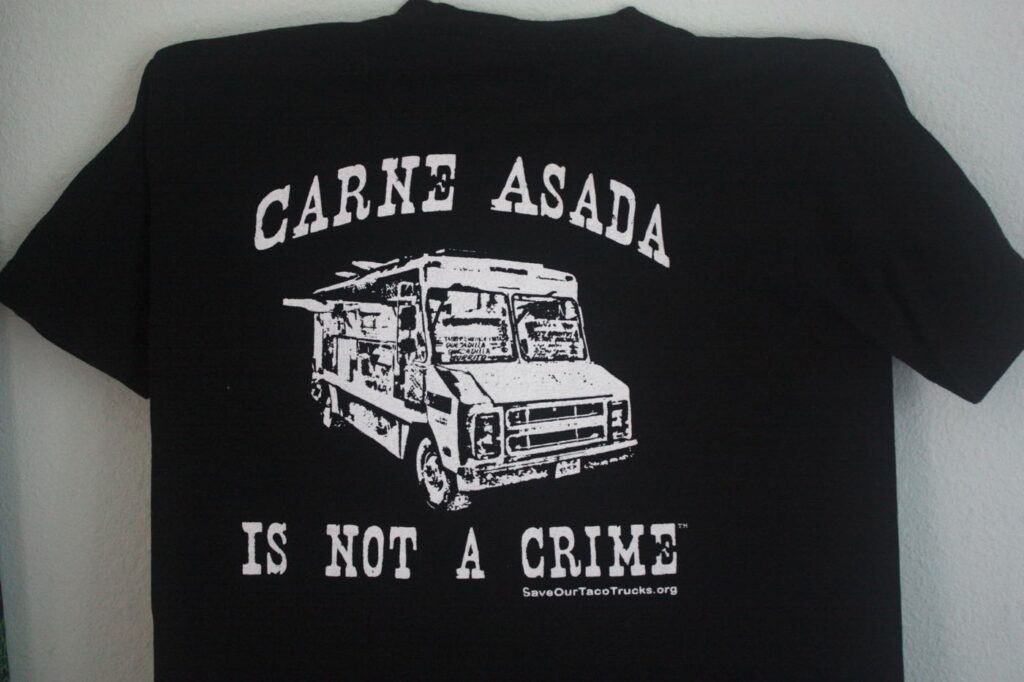

Behold a rare surviving artifact of the Los Angeles Taco Truck War of 2008. The press dubbed it the Taco Truck War. They were right to call it a war. It fits all the specs.

Let’s discuss the field of battle: a time and a place. The year is 2008. The places are Boyle Heights, a Latino neighborhood on the east side of Los Angeles. And, immediately adjacent, East Los Angeles: an unincorporated Latino community under county jurisdiction.

Taco trucks were everywhere in these neighborhoods; they had been for decades. (The locals called them loncherias.) The independently-owned trucks offer cheap, tasty food on paper plates to workers on the go and residents of modest means.

The taco trucks tended to park in the same spot on the same street every day and stay there for hours; that’s how people knew where to find them. The foodies of Greater LA visited also, to trucks that served regional specialties or dishes of the highest quality. Then and now, Angelenos love taco trucks and taquerias and constantly argue over “the best.” A giant golden spectral burrito of a spiritual nature floats over the city. Or it should.

Not everybody loved the food trucks. The brick-and-mortar restauranteurs felt that the trucks leeched off their businesses by parking nearby for free and paying no rent. The truckers responded that they worked hard, charged little, and were subject to more rigorous health department inspections than the restaurants. And that they are just working people, working long hours.

This argument see-sawed back and forth for years. An overtime parking ordinance did exist; but it was little-enforced, and the fines were low. Call it stability — of a sort.

And then the Gold Line came: a metro train extension that would link Boyle Heights and East LA into the MTA subway system for a quick trip to the heart of the city. Work was completing in 2008, with operation to begin in 2009.

Easy transit to downtown brought changes to Boyle Heights and East LA: development! New construction! Gentrification! Speculation! Money! And an influx of big money investors who wanted to make even bigger money.

The big money did not want Latino-operated taco trucks parked all day on the streets of their soon-to-be-gentrified neighborhoods. Especially with crowds of Latinos gathered around them.

So in April of 2008, the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors magically passed a ordinance that would essentially destroy the business of the East LA taco truck. Trucks could only stay in one location for an hour. Then they’d have to drive to a new location at least two miles away. And after another hour, drive to yet another location two miles away from either of the first two locations. This was practically impossible, and would destroy business as it had been conducted for decades.

Oh yes, and the trucks were responsible for cleaning the sidewalks before they left. $1000 fine for each violation. The ordinance would go into effect in September.

This ordinance was introduced by Gloria Molina, the Latina supervisor whose territory included East LA, and a Latina. So it must be politically okay. Right?

Notably, the Supervisors made no effort to inform the taco truck owners of the ordinance that would ruin them. The truck owners were just working stiffs; not hooked into the political flow. Perhaps the plan was for them to just trundle along unawares until one day when the sheriffs started dropping the thousand dollar fines.

It would be the overwhelming frontal assault of the taco truck war! The loncherias would melt away in confusion, and gentrification would proceed apace! Meanwhile, LA had a similar ordinance on the books that it had never enforced. The LA city government prepared to dust it off, and of course in the Boyle Heights neighborhood.

But some people paid attention: some activists, and definitely some foodies. They got the word out. Two history teachers put up a website — saveourtacotrucks.org — with information for consumers and truckers on what was happening and what they could do. And a petition. And catchy slogans like “Carne Asada is not a crime,” and “The revolution will be served on a paper plate!” They sold a t-shirt to support the project: the t-shirt shown above, in fact. Here’s the front of it.

In short order, the LA foodie blogs would pick up on the danger to the taco trucks and further spread the word. Then the LA news media ran with the ball. And then, after not long at all, the national media: TIME magazine, the New York Times, and more.

The taco truck owners organized as La Asociacion de Loncheros L.A. Familia Unida de California. The gourmet food trucks of West LA also organized as the Southern California Mobile Food Vendors. They saw a threat, too, although they moved around more than the East LA taco trucks. And there were demonstrations and protestations and coverage and, eventually, lawsuits.

Lawsuits were the key. The big dirty secret? The ordinances were completely illegal. Invalid. Never should have happened.

California law allows cities to regulate food truck safety but nothing else specifically about food truck operation. Not where they can park. Not how long they can park there, or whether they have to move. A longstanding body of legal decisions in California specifically denies any such specific enforcement powers over food trucks to local government.

The Supervisors and the City of Los Angeles tried it anyway. Never overestimate the intelligence or good sense of a politician. Or underestimate their ignorance, though you’d think somebody’d run the ordinance by a lawyer.

And maybe they did. Perhaps they knew that the ordnance was illegal, and still went ahead. In the best case, they might still roll over the uninformed, unprepared Latino food vendors. And worst case, even making the attempt would satisfy the real estate interests. (“Well, we tried, but the courts…”) I’ll never know. I wasn’t in the room.

The supervisors must have lost their lunch when local resistance solidified and the eastern press paid attention. Especially Supervisor Molina. The LA county supervisors in those days were called “The Five Little Kings,” because each of them represents a district of two million people and has great power. But even kings can can look like jesters.

A lawsuit agains the county ordinance went to trial in late August. The county ordinance was of course ruled to be illegal and unenforceable. The City of Los Angeles ordinance was enforced after that for a time, but also folded under a lawsuit from a stubborn Boyle Heights taco truck owner who gladly took tickets from the cops in a good cause. And he either didn’t have to pay or got his money back; I forget.

And the taco trucks kept rolling, and East LA and Boyle Heights continued to get their cheap and tasty food . The foodies were happy, and hardworking people kept making a living. I have no idea what’s going on down there these days, but all happy endings have a life expectancy.

Nevertheless, what was true once is true always. And if one thing is true in this world, even one thing, it is that carne asade is NOT a crime.

And given the chaos in the service industries as salaries stay low while prices rise and rents skyrocket: maybe the revolution will come on a paper plate.

Beautifly written! I feel like I heard about this while in high school at that time but that was crazy

Thanks very much!