When American settlers got to Northern California 160 years ago or so, they reported that the skies were full of birds. You couldn’t look up, anywhere or anytime, and not see wings in the skies, especially in the wetlands along the coasts and bays.

A hundred and fifty years of guns, pesticides, and urbanization took care of the birds and most of the wetlands. The birds are still there, but you will not look up at any time or place and see, always, wings in the sky.

Until this year in Santa Cruz, along the coast. The birds were back — in force. Vast formations of pelicans moved across the sky like bomber wings from some grainy wartime film of airstrikes on Occupied Europe.

Imagine if you will a thousand flying Thanksgiving turkeys with eight-foot wingspans moving through the air toward you in lop-sided “v” formations. From as far away as the eye can see. I say “a thousand,” only because a thousand passed my seat on the beach. In ten minutes. And though I stopped counting, they kept coming.

And not just pelicans: clouds of snake-necked cormorants, flights of exotic gulls from far away lands. And, in the water, several hundred humpback whales churning the sea as they breached and dove in unprecedented number. Attending them were hundreds of sea lions – essentially, 600-pound sea-going bears that hunt in packs.

They look sort of cuddly. From a distance. With the long lens, you see the fangs.

On the harbor, pelicans, gulls, cormorants, and even egrets mingled and screamed together in one gigantic avian block party. They filled the rocks. They filled the harbor. They filled the skies. I’ve never seen anything like it. Nobody had.

And finally, after all the rest, came the Germans.

I can’t know precisely how many Germans visited Santa Cruz in October. But for a few weeks you couldn’t walk down Pacific Avenue or enter any restaurant or business of note without the sound of Deutsch drifting into your ears.

Strange circumstances brought the Deutsche to Santa Cruz. Yosemite National Monument, one of the scenic wonders of the western world, closed its gates in early October thanks to the temporary shutdown of our federal government by a dysfunctional political class. Thousands of overseas visitors were left forlornly waving their tickets at the locked gates – metaphorically, at least. A great many of them were Deutsche, or Deutsch-speakers.

The Deutsche spread out over Central California looking for sights or activities that might salvage their carefully-planned vacations. Not a few of them were drawn to the Santa Cruz area by promises of spectacular whale-watching. They crowded the tourist boats that regularly plowed through pods of 30, 40, or 50 giant humpback hanging close offshore. When Yosemite’s been wrenched from your grasp, a slow cruise through a flock of prehistoric sea monsters is no mean consolation prize.

And what did all this? Why did all this happen? What brought ten times the normal number of pelicans, the sea lion invasion, the foreign gulls, the pods of forty-ton whales? And the dolphins and killer whales that I didn’t even get around to mentioning?

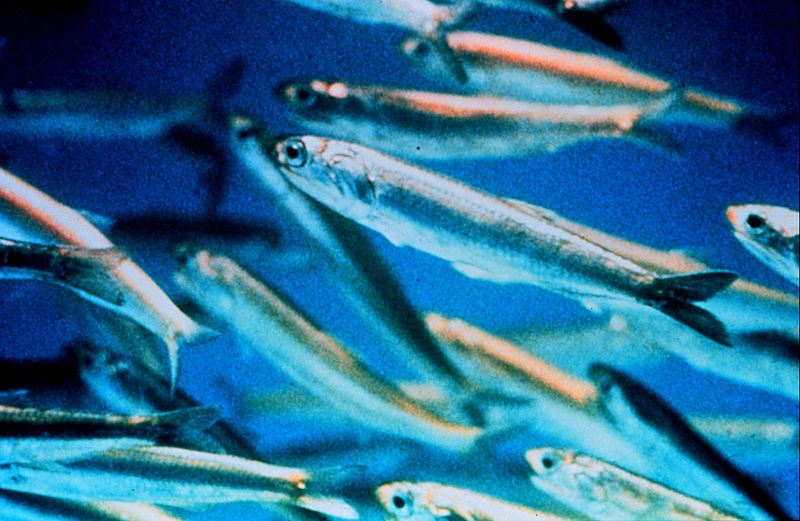

An anchovy. A small silver fish did all this: him and a billion of his close, personal friends.

This year the Monterey Bay experienced anchovy runs of unprecedented size. Nobody knows why. Just that, as far as the marine mammals and sea birds and predator fish were concerned, the bay was filled from end to end with small, silvery cocktail meatballs. And they just kept coming.

Some of the schools stretched for a mile or more. You could spot them by the massive, writhing cloud of birds that formed above them. At rapid intervals pelicans would drop from the sky like bombs on the fish below.

They’re shock-fishers, pelicans are, who stun their prey by the force of their bodies hitting the water from 50 feet up. And with the pelicans came the gulls, who fish from the water’s surface, but also specialize in stealing fish from pelicans. The fishing would be so good that some pelicans didn’t even bother to dive; they just fished from the surface.

Dive-fishing is a learned skill for pelicans, and many young ones starve before they get the hang of it. But none starved this year. Even the slowest had time to learn the ropes. With so many fish, they could not fail.

Anchovy tend to get stuck in the our harbor; they find their way in, and then don’t know how to leave. Thus you would see skirmish lines of sea lions running up and down the harbor to harvest the fish. I watched them do it for half an hour.

Out to sea, where you saw a herd of sea lions feeding you might see whales, also. When they’d had enough to eat, the sea lions amused themselves by herding anchovies into the mouths of the humpbacks, for fun. Humpbacks can eat two tons of anchovies a day. (I didn’t take the following picture.)

So all hail the humble anchovy, even if it is nothing more than nature’s taco chip to the birds and fish and mammals above it in the food chain. It did so much: bring the kingdoms of the sea together in one long festival of consumption; save the young pelicans; promote interspecies cooperation between whales and sea lions; make happy the dour German tourists and enrich the tour boat operators; and show we locals a spectacle of crowded seas and skies not seen in our lifetime.

As I write this, the party has ended; the anchovies moved on, and so have the whales and the surfeit of pelicans and migratory gulls and other birds. The young pelicans who grew up at a virtual buffet table of fish will now face more meager prospects, and many competitors; Mother Nature always bats last.

But in a nation where humans themselves increasingly live in uncertainty and need, it gave me deep pleasure to see the animals, at least, have a fine fat season of their own. Thanks to the humble anchovy.

So is the anchovy the fish of the year?

No.

The Alaskan artist and humorist Ray Troll, who loves fish above all things, likes to say “We are all fish.” He regards evolution and the ways of nature with a reverence that most people save for their gods. And he likes to make the point that humans are nothing more than fish that evolved to live on land. Our brains, backbones, guts, limbs, blood: all from our fishy ancestors. Just, modified by the evolution that Troll loves.

The Alaskan artist and humorist Ray Troll, who loves fish above all things, likes to say “We are all fish.” He regards evolution and the ways of nature with a reverence that most people save for their gods. And he likes to make the point that humans are nothing more than fish that evolved to live on land. Our brains, backbones, guts, limbs, blood: all from our fishy ancestors. Just, modified by the evolution that Troll loves.

As a race, we are anchovy and predator in one. We are our own sustenance; we all produce, we all consume, and we all share, or should. We are the anchovies who feed the sea lions, and the sea lions who feed the whales. We can produce for ourselves a plenty that ten billion anchovies could not match.

And yet, these days it doesn’t work that way. There is more than enough, or can be; but it isn’t shared. A few big fish get bigger; the rest dwindle.

And it has gotten to the point where the Roman Catholic Church had to take a strong and uncompromising stand on world inequality. This year the Roman church, which takes the fish as one of its oldest symbols, announced for the record that the rise and enshrinement of greed in our civilization is in fact a sin against God and a crime against humanity.

Pope Francis went public on the topic in November. Some excerpts:

“We have created new idols.The worship of the ancient golden calf has returned in a new and ruthless guise in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose. The worldwide crisis affecting finance and the economy lays bare their imbalances and, above all, their lack of real concern for human beings; man is reduced to one of his needs alone: consumption.” And:

“I am interested only in helping those who are in thrall to an individualistic, indifferent and self-centered mentality to be freed from those unworthy chains and to attain a way of living and thinking which is more humane, noble and fruitful, and which will bring dignity to their presence on this earth.”

For this I declare Pope Francis, big fish and big fisherman rolled into one, the Fish of the Year. I’m not a perfect fan of any spiritual practice or religious sect; I capitalize the “c” for no church. But this pope knows that we are the fish who must feed each other, and will say so.

For this I declare Pope Francis, big fish and big fisherman rolled into one, the Fish of the Year. I’m not a perfect fan of any spiritual practice or religious sect; I capitalize the “c” for no church. But this pope knows that we are the fish who must feed each other, and will say so.

Many of us think this way; it seems obvious, a low bar to jump intellectually. But we are not world leaders in thrall, as the pope might say, to the idolatry of money. Of all the leaders, only the Pope will say it as it is and make the money face the morality. Because morality is what brings a balanced ecology in which all human fish can thrive. Even Ray Troll might agree.

And if for the time being the fish in the lead of that earth-girdling school of human anchovies is wearing a small red miter: so be it. Have a hopeful New Year. Swim well.

Pingback: Secret Santa Cruz – Fish of the Year | Santa Cruz Community Media Lab