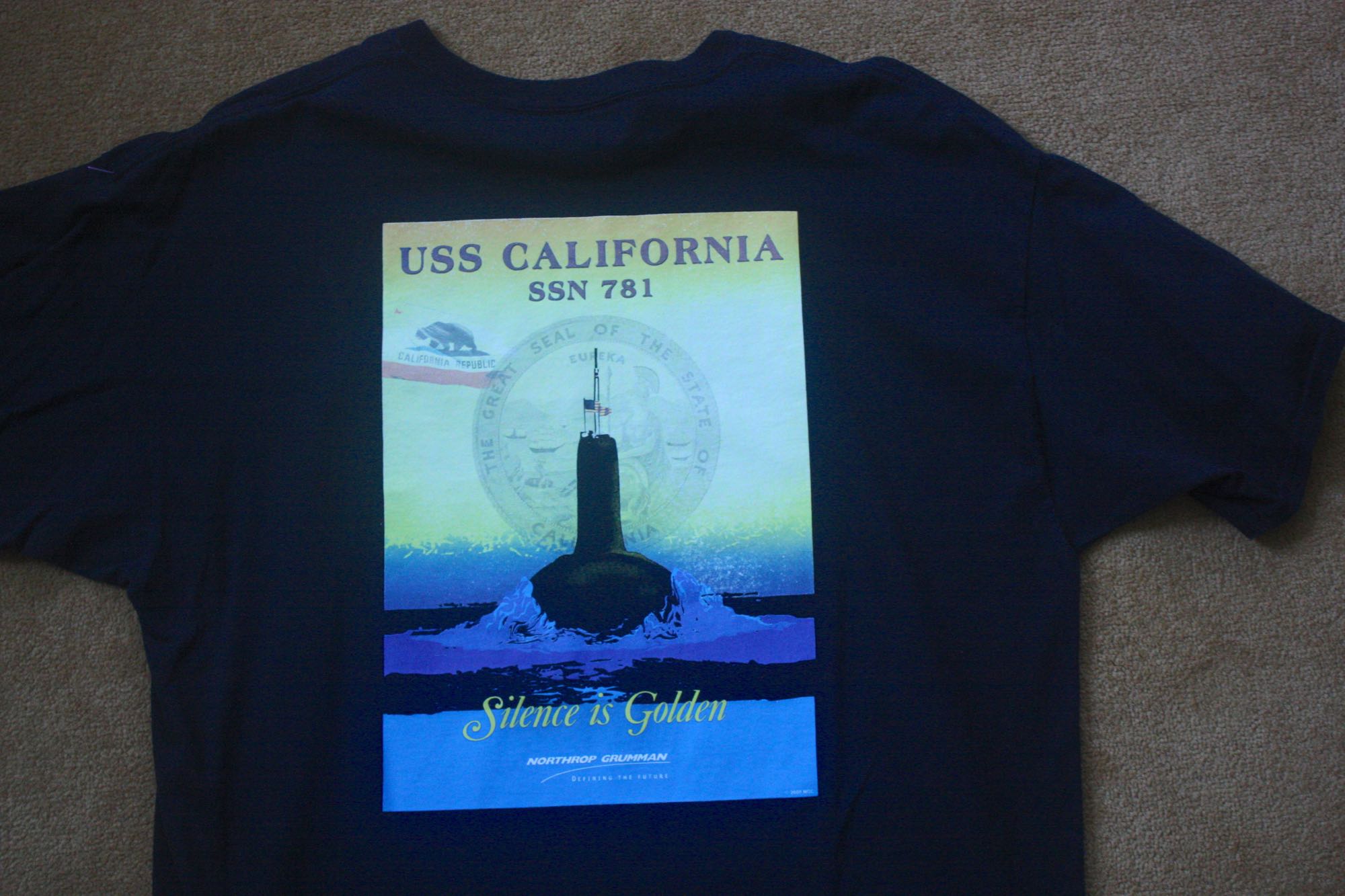

This scenario occurred to me upon snagging the latest t-shirt for my collection:

Suppose that you live in Santa Cruz County, home to alternative lifestyles. It’s also the home of hope for a greener, better, more peaceful and non-authoritarian tomorrow.

And beyond that we Santa Cruzans all hope that all the world’s peoples survive the next 50 years without nuking each other to glass, despite the pressures of growing shortages and environmental catastrophe.

And you agree with much of that. But you’ve got to make a living, too. And sadly, your living comes from the military industrial complex.

One day, to commemorate a very special occasion, your management gave you this rather wizard t-shirt. And you deserve it, because your team helped roll out a $2 billion nuclear-powered attack submarine: the USS California, SSN 781. This shirt honors the commissioning of that vessel in 2011.

The California is the pride of the Virginia Class submarines and yet another guaranteed cost-plus-profitable project for your employer, defense contractor Northrop Grumman. SSN 781 is a veritable Stradivarius of destruction; although these days, the defense establishment prefers the term “force projection.”

Northrop Grumman, of course, is one of the ever fewer, ever larger defense contractors who provide America with its weapons — and increasingly, even run weapons programs for the government. Ain’t private industry wonderful? It can be part of the government, and run a guaranteed profit, too.

And you, the minion who got this wondrous shirt, went home and put it in a drawer. Seven or eight years after the fact, it’s in mint condition. You never wore it; once at most, at the office party. No doubt you’d feel uncomfortable wearing it in Santa Cruz. Would they understand at the farmer’s market, as you dithered over your organic heirloom tomatoes?

Perhaps not. In some parts of this county, somebody might just hiss at you over that shirt. In other parts, the more monied parts — it’d just be bad taste. One does not talk about where the money comes from; one simply has it.

A few years later you got tired of having the t-shirt stare at you from the drawer, and you donated it to a worthy charity. They put it in their thrift store. Now I have it.

Take a good look at it: look at all the California iconography. There’s the Great Seal of the state; there’s the Bear Flag. Even the name “USS California” is printed in an old-school 19th- or 20th century font. The ship’s motto, “Silence is Golden,” refers to both the Golden State, and the ship’s stealthy nature.

Yes: someone made a nice try at establishing a 21st century killing machine as a part of California’s heritage.

And you know what? It’s true. It’s all true. This nuclear boat has 200 years of heritage, or almost. Back to before we were even part of the United States.

The year is 1822, and in Cornwall, England, a young boy named Joshua Hendy was born into the world. Cornwall sucked, so he and his brothers migrated to the US while he was a young teen. After traveling the South, he married and settled in as a blacksmith in Houston in the 1840s.

Yellow fever killed his wife and children; after that Houston had little to hold him. When gold was discovered in California in ’49, Hendy hopped a clipper ship for San Francisco.

Hendy found his fortune in San Francisco insted of the Gold Country. At first, he made tools for the prospectors and then, equipment for the big mining operations that came soon enough: pumps, ore crushers, grinders, ore concentrators, giant water cannon.

Hendy proved to be an engineering genius, and the Joshua Hendy Iron Works was the engineering company that made the Comstock Lode mineable. Some of his designs for mining equipment were still current 100 years later.

Hendy passed in the ‘90s, but the Hendy Iron Works chugged on. It even made machines to carve out the Panama Canal. When the 1906 quake wiped out its San Francisco headquarters, the city of Sunnyvale offered the company free land if it would relocate to the South Bay. It did, and became a (very) early technology company in what would become Silicon Valley.

During World War I, the Hendy Works was asked to make two-story tall marine steam engines for cargo ships. The company had never made marine equipment before, but the giant units that they turned out were later prized for their reliability and durability.

Flash forward 20-odd years through the Great Depression and some really bad times. The Hendy Iron Works was down to 60 employees. Financially it was on the ropes, with the banks closing in. But a hard-driving engineer named Steven Moore bought the company and refashioned it, with the backing of a consortium of western engineering firms.

Moore ramped the company up to 11,000 employees during World War Two to mass-produce old-fashioned but durable marine steam engines at a clip that nobody could believe.

Joshua Hendy 2500 HP Triple Expansion EC-2 marine steam engines would power the Liberty ships that the Kaiser yards were building in the East Bay. The plant turned out one 136-ton, 20-foot-tall steam engine every 40.8 hours. The Hendy Works built over 750 of them in three and a half years, plus dozens of more modern steam turbines for faster vessels.

Moore moved on after the war, and Westinghouse Corp. bought the Joshua Hendy Iron Works. The company began making pressure hulls for submarines, control and missile-launch systems for nuclear subs, radio telescopes, steam turbines for use in power generation, nuclear power plant equipment and more. Northrop Grumman bought Joshua Hendy from Westinghouse in the ‘90s and renamed it Northrop Grumman Marine Systems.

And it was that unit, the Joshua Hendy Iron Works of old, that served as prime contractor for the USS California project — even if the actual boat was built in Northrup Grumman’s East Coast shipyards.

The Northrup Grumman PR flacks had it right, whether they knew it or not. The USS California was a California boat from a California lineage: all the way back to the Gold Rush.

But… somebody really didn’t want to wear that t-shirt in Santa Cruz County. And I don’t blame them.