Lets talk about skulls on t-shirts. And skeletons, too, but mainly skulls.

Once upon a time, skulls were an unambiguous symbol for death and danger. What else would a skull mean?

Back then, only outlaws wore skulls on their person. But after World War Two, outlaws got more exposure: the new outlaw motorcycle gangs made a splash in the media. They wore skulls on their clothing, and this caught the eye of the general public. . Someone who dabbled in the black arts might wear a skull also. Again, more fodder for the public eye. A skull still meant trouble. Though it began to mean “rebellion,” too.

These days, any 14-year-old can buy “trouble” and “rebellion” and danger for $11.99 at Target: on a t-shirt, a hoodie, a polo shirt, a belt buckle, a woman’s dress or scarf, even a polo shirt. Whatever you want. Have a skull.

These days, any 14-year-old can buy “trouble” and “rebellion” and danger for $11.99 at Target: on a t-shirt, a hoodie, a polo shirt, a belt buckle, a woman’s dress or scarf, even a polo shirt. Whatever you want. Have a skull.

And so skulls lost their dreadful impact. A fashion writer for the New York Times got it right when he said, “The skull is the “Happy Face” of the 21st Century.” Like the Happy Face, a skull on your t-shirt can mean anything you want it to:

“I’m wild and crazy;” or “Life is short, enjoy the ride;” or “I’m a member of a fandom that you’re not cool enough to join;” or “I’m a rebel, or want you to think so;” or, “I’m just lightly rebellious and want to tweak you a little, made ya look, haha.” Or even, “I miss Jerry Garcia.”

“I’m wild and crazy;” or “Life is short, enjoy the ride;” or “I’m a member of a fandom that you’re not cool enough to join;” or “I’m a rebel, or want you to think so;” or, “I’m just lightly rebellious and want to tweak you a little, made ya look, haha.” Or even, “I miss Jerry Garcia.”

Given all that, how could skulls not lose their impact? My breaking point came via a toddler wearing turquoise jammies with a pattern of black skulls. He was leading his paunchy GenX parents down Santa Cruz’ main drag. Toddlers don’t usually choose their own jammies, so I’ve gotta believe that their parents thought it cute. “Look, Tyler’s such a little BADASS… just like us.”

Yes: look. At their most basic level, skulls make you look. Because they’re skulls. What else is fashion about anymore but making someone look?

There’s a theory about the skull’s transition to mainstream fashion statement; we’ll touch on it later. In the meantime, here’s a gallery of skull tees. In my opinion, the skull is the single most popular t-shirt graphic. And as I said above, people incorporate it in many different kinds of message.

“Pay What You Owe, or Else”

Bail bondsman cultivate a tough reputation with their customers. Some of them would like you to think that they’re as tough as biker gangs. Because if you put up a $20,000 bond to get a guy out of jail, you want him scared enough to show up for the court date. Otherwise, he might “forget,” and you’re out twenty grand.

Hence free t-shirts for clients with ominous skull imagery. These bondsmen want you to know that they’re tough mofos who’ll come after you and drag you back to court kicking and screaming.

Not all bondsmen use the skull. Some just tell you that they’ll get you out of jail quicker than anyone else. (Hint: they won’t.) A self-professed “Christian bail bondsman” told me that he treated his clients with more love and respect that the average bondsman. He even steered them towards help for their many problems. But if they ran out on him, he’d come after them just like the badass skull mofos.

Because even a Christian bondsman has to get his money back, or he doesn’t stay a bondsman for long.

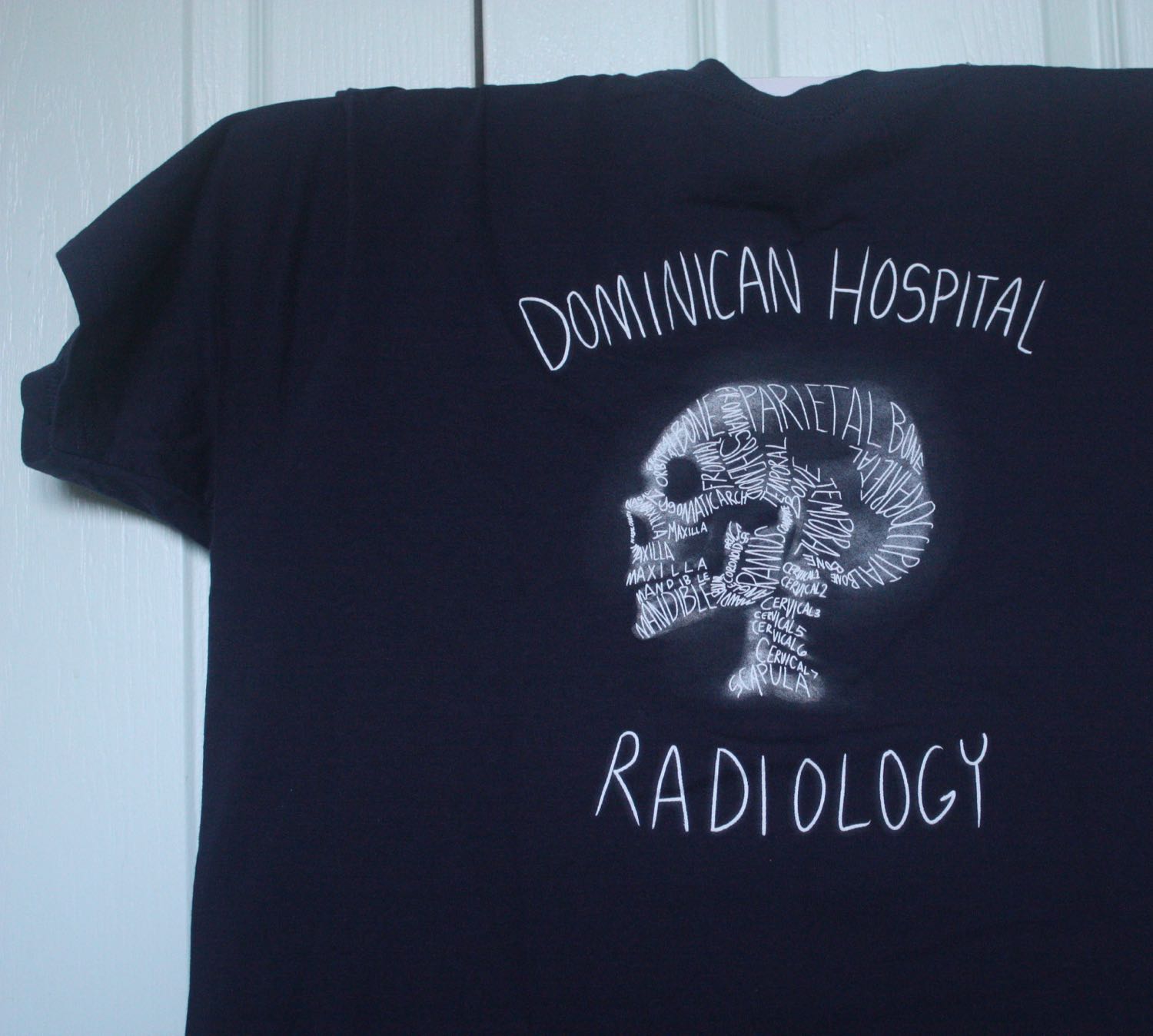

“Looking at Skulls is Our Business”

Radiologists love skulls, too. It’s their job to x-ray the damned things. This t-shirt from the Radiology Department at Santa Cruz’ Dominican Hospital is both attitudinal and educational. The “skull” is made up of the names of a skull’s component bones. Radiologists know them all. And as somebody pointed out to me, it’d make a rather good album cover. If there were still albums. Are there?

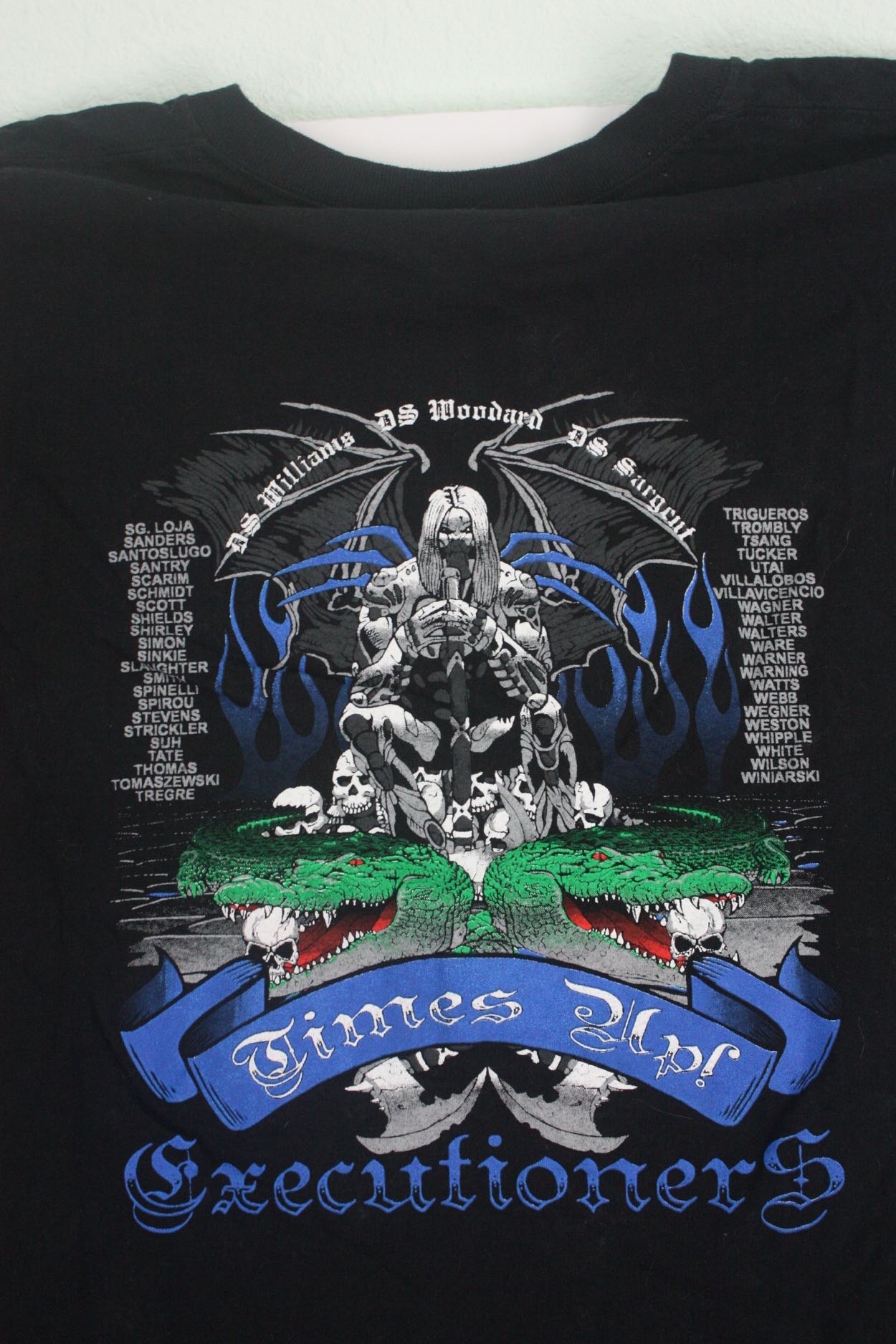

“My Drill Instructors are SKULL-LOVING DEMONS, and I STILL Survived.”

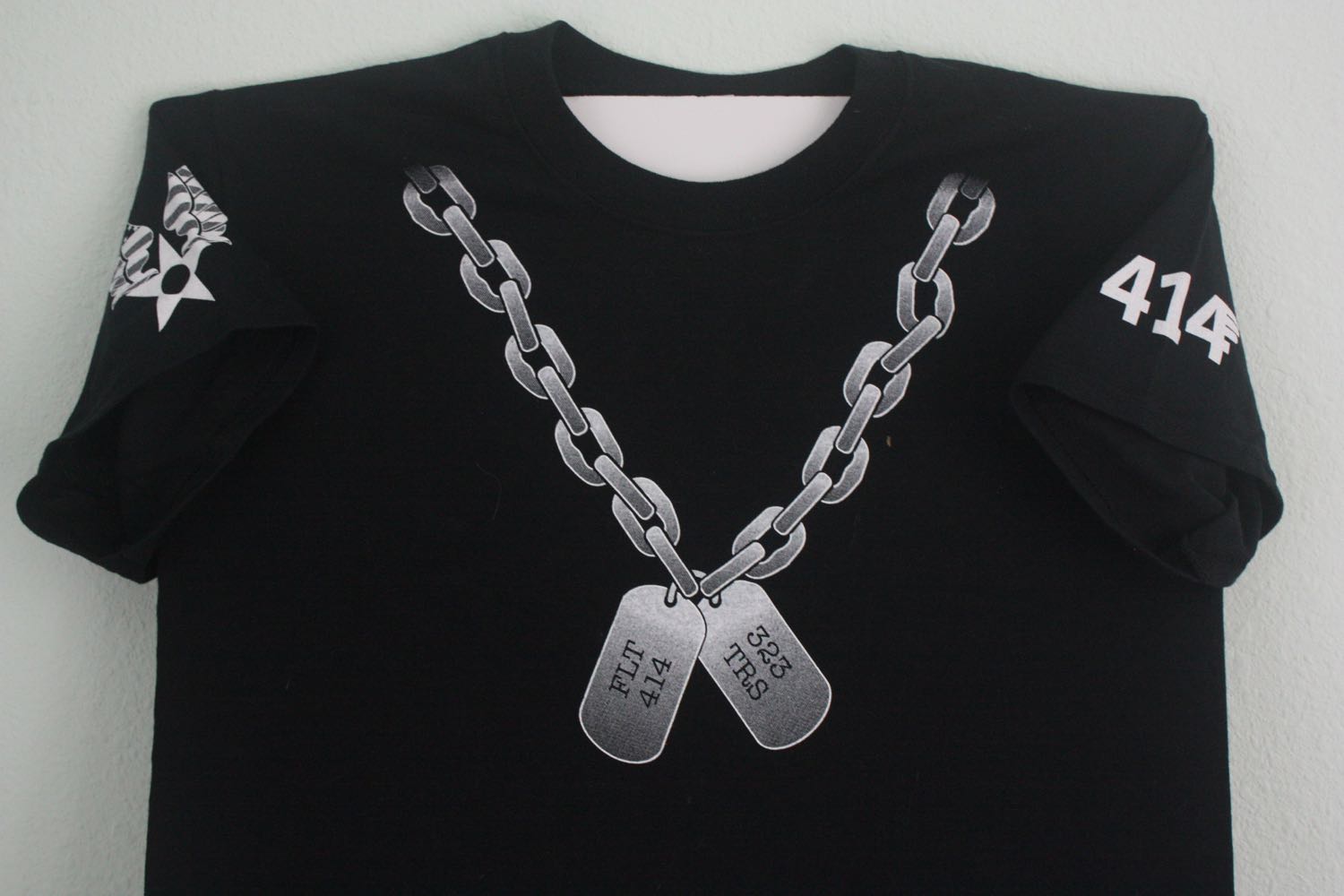

Up to a few years ago, it was common for soldiers in basic training (boot camp) to get a graduation t-shirt from their unit. Consider it a sort of yearbook for their training company, or training flight, or what have you.

All these tees were laid out the same: the nickname and number of the squadron at top or bottom, the names of the boots down either side and in the middle, a killer android or sword-wielding demon crouching on a pile of skulls.

If you want amateur iconographic interpretation: the monster represents the drill sergeant, the source of all pain and terror. The skulls represent all the crap that were thrown at the recruit, I suspect. Sometimes the skulls sit on a base of alligators; sometimes in a pool of blood. Sometimes both.

That’s my interpretation, but it may be true, because the skulls are always there. And of course they’re part of the macho warrior culture that the services try to sell recruits. Even if they’re going to end up loading cargo planes at Travis Air Force Base.

I’m pretty sure these tees were the work of one t-shirt business. It provided t-shirt layout software that one of the boots could populate in from a library of bloody images. Some tees give credit to a “designer.”

All the boot had to do was plug words and images into a template, pick and size font, and email the files to the company. T-shirts would then be shipped. It would have worked just like church cookbooks, only with blood and skulls and monsters.

All the boot had to do was plug words and images into a template, pick and size font, and email the files to the company. T-shirts would then be shipped. It would have worked just like church cookbooks, only with blood and skulls and monsters.

I should mention that I’ve never seen a single person, ever, actually wear one of these these tees. Outside the special goldfish bowl that is the military, people would point and laugh. Perhaps inside, as well. If you want one, though, try Goodwill Industries. It shouldn’t take more than a trip or two.

You can still buy graduation t-shirts for your favorite boot online; a variety are made for specific training units, and you can add your loved one’s name. But the soldiers don’t design the tees themselves anymore — at least, not that I’ve seen — and the new ones aren’t nearly as much fun.

“We Like Skulls and We Carry Badges. Don’t Ask a Lot of Questions”

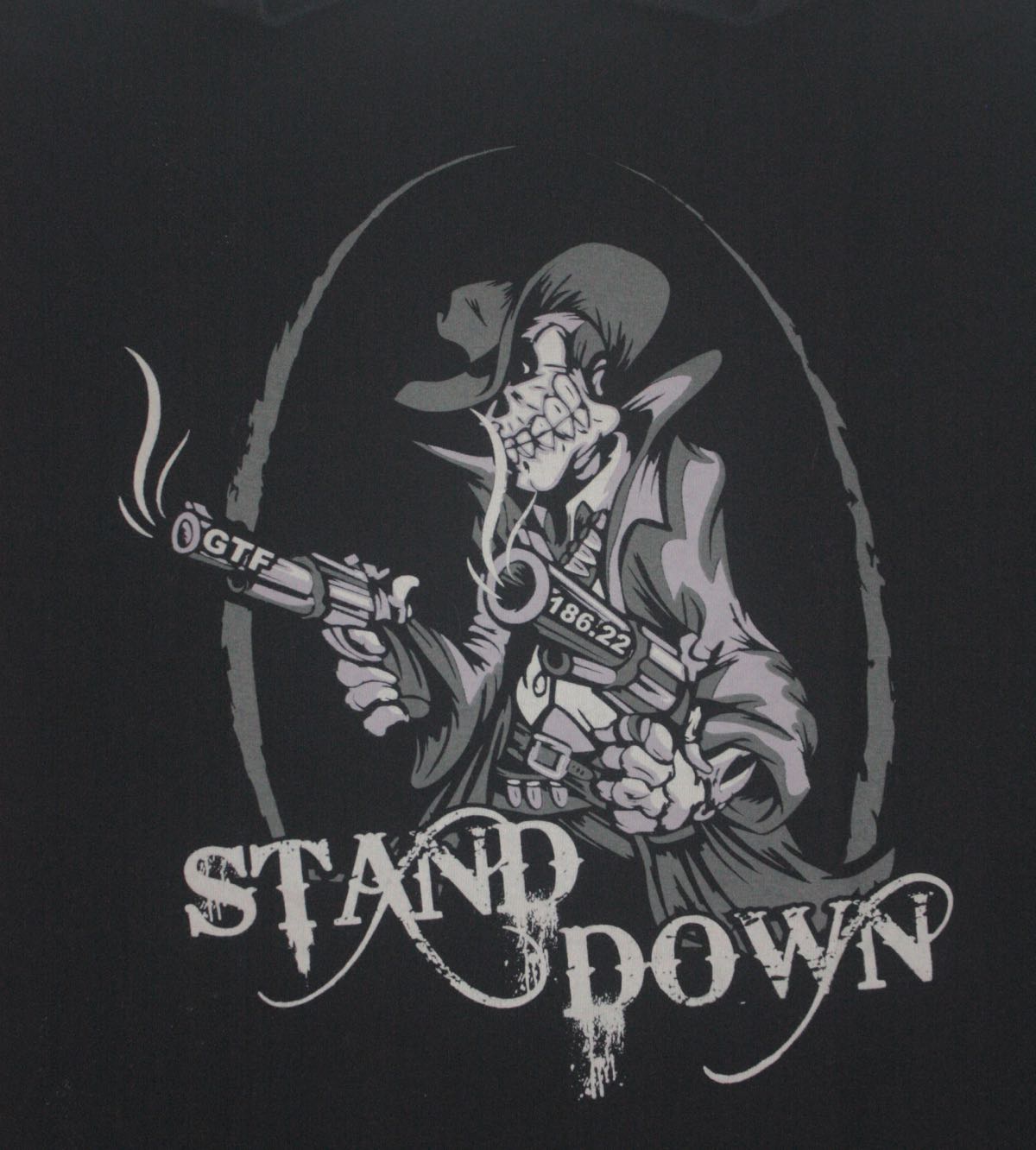

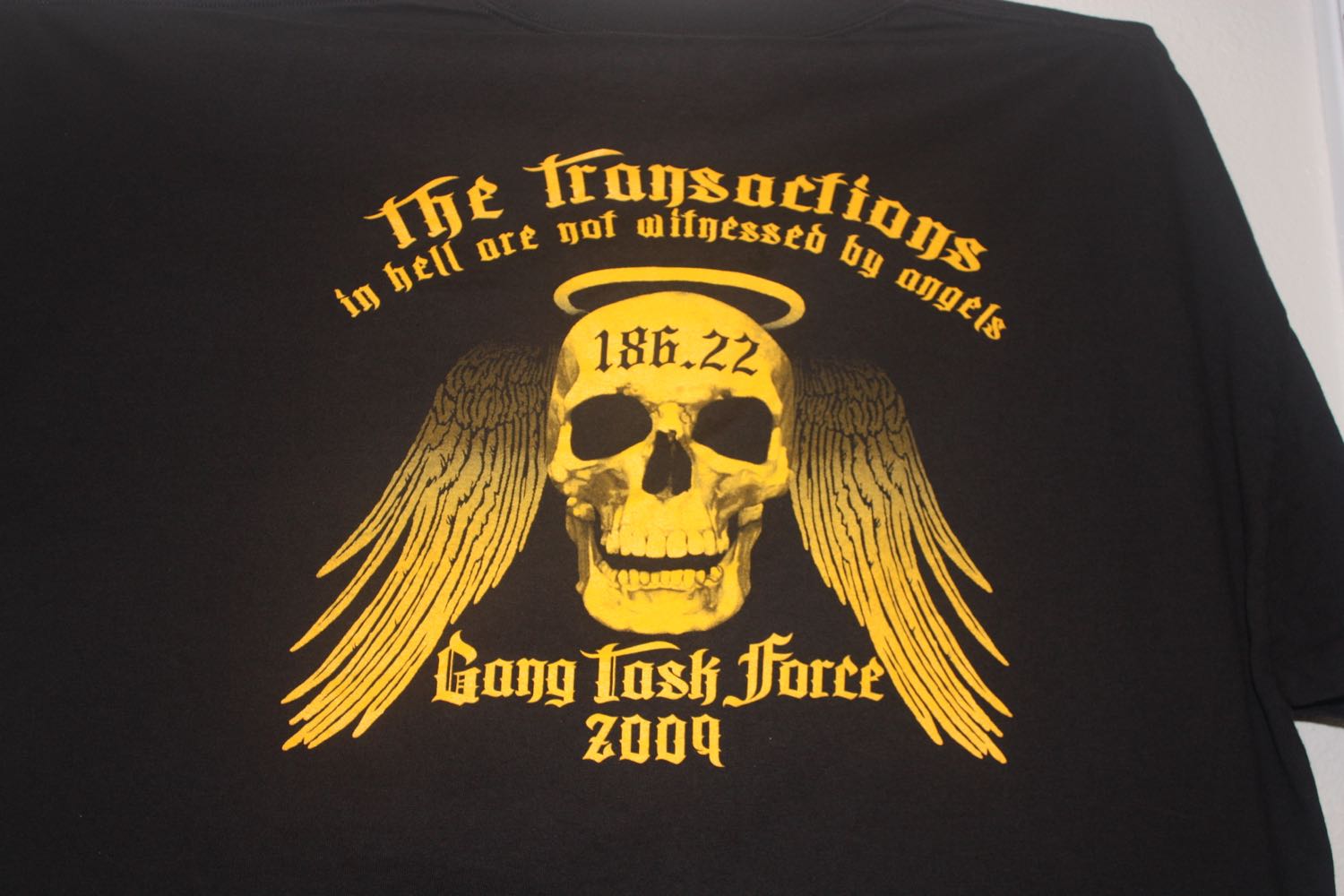

The tees in this section come rom law enforcement: specifically, from anti-gang task forces. That said, they carry about as many secret signs as a Hell’s Angels t-shirt. And as many skulls. And as much menace.

A gang task force is a county-wide or region-wide law enforcement group tasked with controlling gang violence or drug trafficking. It can be completely a creature of the sheriff’s department, or a coalition of different law enforcement agencies.

First off, note that these tees are anonymous; they don’t identify their sponsor agency or county. Even the term “Gang Task Force” is sometimes abbreviated to a cryptic “GTF.”

First off, note that these tees are anonymous; they don’t identify their sponsor agency or county. Even the term “Gang Task Force” is sometimes abbreviated to a cryptic “GTF.”

This is intentional. The t-shirt messages are dire and frankly, the grinning, gunslinging skulls are supposedly the good guys. But they don’t look like good guys. If that’s how law enforcement chooses to express itself, best to stay anonymous.

In California, task forces wage a never-ending campaign against violent Latino street gangs, Norteno- and Sureno-affiliated. They operate drug-dealing networks, and they fight each other. The street gangs take direction from competing Latino convict networks in the state prisons. There’s a formidable web of organized crime in play: no question. There is a need for a gang deterrent that goes beyond city limits.

I’m bugged by what these shirts imply, though: that gang task forces don’t always worry about the legal nicities. The challenge is there: “Want us to follow the rules? Or actually catch the bad guys?” Take a look at this tee:

Can you parse the message? It’s not hard.

It is possible that these t-shirts were not issued by or for a particular agency. They could be third-party tees that officiers can buy for themselves. Even if so, I’m not reassured.

It is possible that these t-shirts were not issued by or for a particular agency. They could be third-party tees that officiers can buy for themselves. Even if so, I’m not reassured.

Other things to look for in a GTF tee: the number 186.22. Section 186.22 of the California Penal Code both defines criminal gang activity and specifies special punishments for activities directed by or in aid of criminal gangs. It is the charter of California gang task forces, and their chief legal resource.

As civil servants, the members of gang task forces also attend gang conferences and belong to gang-centric law enforcement groups. These operations issue tees with the same imagery, and of course the number 186.22.

Apologies for all the conjecture. But one of these days I’m going to find a lawman who doesn’t mind filling in a few gaps for me — in the general sense, at least.

“I’m DEAD, and I like T-shirts”

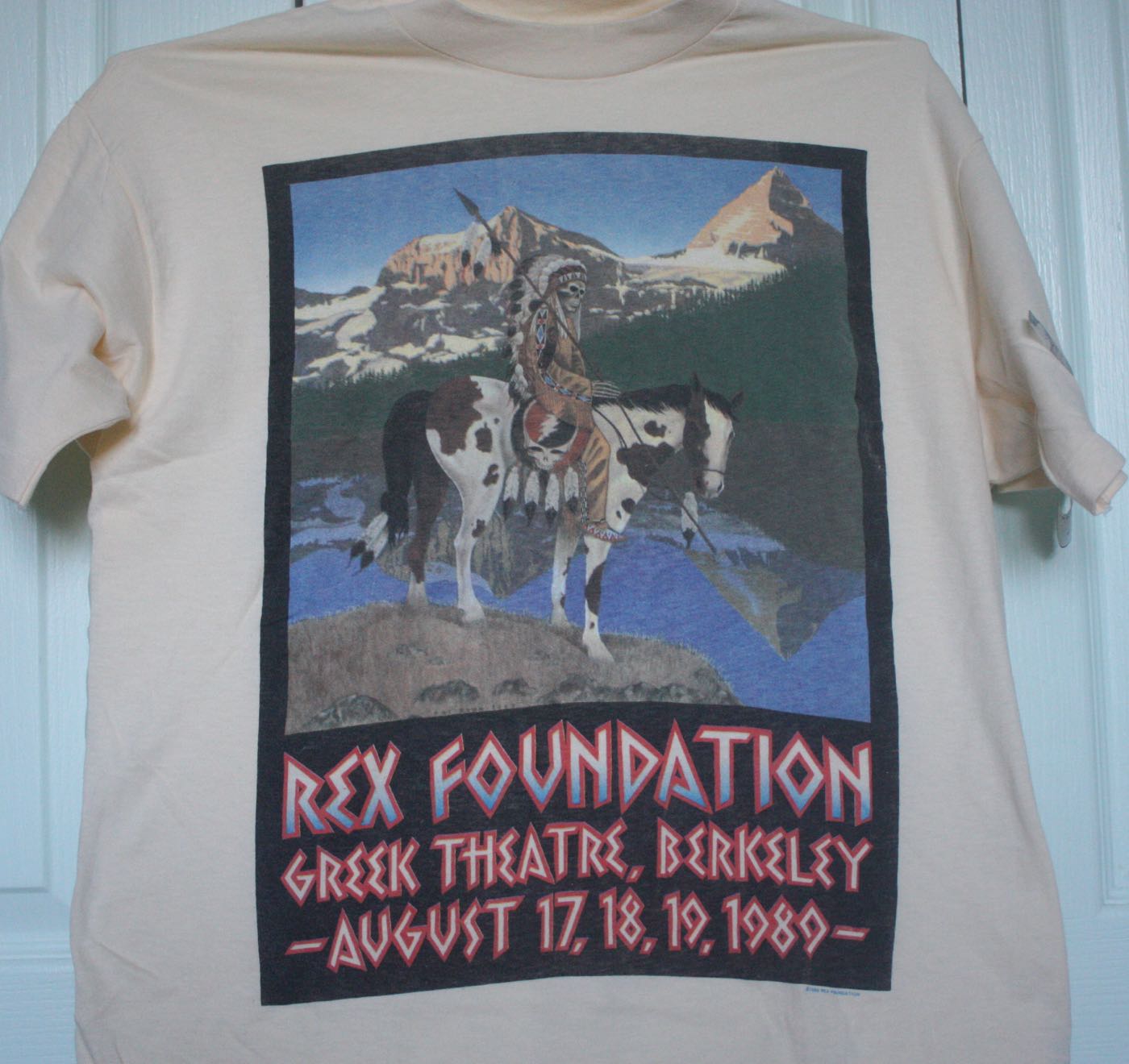

When the subject turns to skulls on t-shirts, you can’t ignore the Grateful Dead. They and promoter Bill Graham (through his Winterland Productions) began issuing bold t-shirts by the early 70s, when skull imagery was common only to biker gangs. A Dead shirt almost always features a skeleton; or a teddy bear; or both.

But the Dead weren’t bikers, and neither were their fans. As the Dead saw it, they were out to enlighten, not frighten. They believed that they and their fans were showing the way to a better world. The name “Grateful Dead” is a folklore term for souls of the dead who bring good fortune to a living man who paid for their burials or otherwise made sure that they were buried respectfully.

I have few Dead t-shirts. The one shown above is a parking-lot bootleg, probably sold at an informal stand outside a concert or festival. The one below was produced for a benefit concert held for the Rex Foundation. The words “Grateful Dead” appear nowhere on it, but it’s a Dead tee through and through.

The Rex Foundation was the Grateful Dead’s charity arm. Beginning about 1983, the members of the Dead would agree upon a cause that they wanted to give money to — scientific, educational, or very often environmental. Then they would hold a concert or two to specifically to raise money for the cause, and give it to them. Hence this t-shirt for a fundraising concert in ’89. The name “Rex” paid tribute to their old road manager, who died in the ‘70s.

By the time the ‘70s were over, skulls had spread to other band tees, especially in the emerging heavy metal genre. Metal was fairly dystopian and aimed at disaffected teenage boys, so skulls were a natural choice. Not the only choice, but common enough.

By the late ‘80s licensed rock metal tees of all sorts were widely available in mall-based teen clothing stores: every rebellious headbanger in America could have their own skull.

Some journalists and enthusiasts link today’s wide acceptance of skulls today with this wider availability of graphic metal/rock clothing. I suspect that they’re right; those ’80s- and ’90s-era headbangers are all middle-aged now, or close. They grew up with skulls. Beyond that, the Disneyfied “Pirates of the Carribean” movie franchise in the early 2000s sealed the deal for skulls as a family-friend symbol of… whatever you want them to be. A Smiley Face for troubled times.

And so in the greater scheme of things, what perhaps started with the mellow Grateful Dead, continues with… Paparoach.

I’ve seen cute window stickers on suburban vans depicting a family of skulls – dad, mom, cute little pig-tailed-girl skull, cute little boy skull, cute baby skull. Also, book cover graphics use skulls to excess and in all kinds of ways that our parents wouldn’t have understood. It’s some kind of leitmotif that somehow just about everyone wants to use thematically.

LK: yes, skulls are now acceptable almost everywhere. They express a now-mild form of — not rebellion, but differentness, whether real or not. And they make you look. Put those two together, and you have a powerful marketing tool.

The skull’s popularity may also reflect a society that’s distant, in general, from actual, physical danger. In a situation where rotting bodies were common, some might not want to put the skull on their two-year-old anymore.